Can a Film Slate Make More than a Tech Portfolio?

Edit from the future: Maybe, but probably not, and don’t count on it.

In a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, “The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.” He also called it “The 8th wonder of the world, he who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t pays it.” In this post, we’re going to be examining how we can use the notion of compound interest in comparison to tech and film investments.

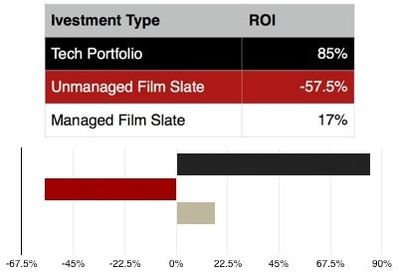

In the previous installment, we looked at the average ROI of a film slate vs. an early stage tech portfolio. Here’s what we came up with before. For the full tables and Metrology, check out last week’s post.

Unfortunately, the numbers don’t look good for film. By the math above, we can see that tech portfolios make on average of 7.5X what a film slate would over their lifespans.

But, film does have one advantage over tech. The amount of time that it takes for a film to recoup [if it’s going to] is much shorter than what it would take for a tech exit would be.

For instance, the average time from when an Angel becomes involved in a project to when they see their money back is around 12 years. For a film to at least start recouping investment, that time period is around 2-3 years, if it’s done well and distribution is planned from the beginning.

Why is that? Generally, for a tech investor to get their money back, the company they invested in has to either be acquired by a larger company or make an initial public offering [IPO] and be listed on a stock exchange. Sometimes an investor will be able to list their stock on a secondary exchange, but that’s a little beyond the scope of this article. Acquisitions tend to happen more quickly than IPOs, but there’s generally less money and less prestige.

Given that the size of venture capital [as opposed to angel investment] rounds have ballooned in the last decade, many venture capital firms are pushing their companies to IPO instead of be acquired. This may make the time from an early round angel investment to exit take even longer than the 12 years mentioned above.

Films, on the other hand, start getting some of their money back shortly after they start distributing the film. If the filmmakers get a minimum guarantee [MG] they may get a decent check up front. If they don’t, they may not, and it may take an additional year or so to start getting their money back. I should note MGs are more the exception than the rule.

So for this exercise, we’re going to look at the APR of both a technology investment portfolio and a film slate. We’re going to make the assumption that both investments are early stage, since the angel round for a technology company is very early in the investment process, generally directly after the friends and family round. Later rounds are generally dominated by institutional investment firms. A similar scenario can be said about film. Most angels from other industries get involved very early, since they don’t have contacts with completed projects.

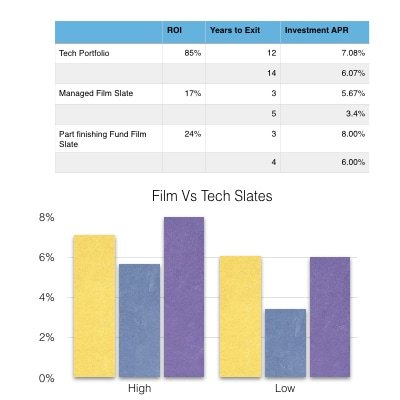

Since revenue from a film tends to come in over time, we’ll count the lifespan of a film investment to be 3-5 years as opposed to the 2-3 years mentioned above. 3-5 years should be enough time for 60-80% of a films total revenue to come in on average. As such, since this series is largely a thought experiment we’re going to think the general earnings of a film to come in overt that shortened timeframe. Tech exits on the other hand generally come with a large lump sum for the investor after a quite a long time that may be getting longer, we’re going to do the math based on 12-14 years to exit for a tech company. Some do come in much faster, but some films also get bought out for millions after 18 months. They’re outliers and not generally worth accounting for when planning to pitch an investor.

Tech portfolio APR

When we compare APRs, this is starting to look a little more reasonable, but still not great. When we compare the APR of a film as opposed to a technology company, we’re only looking at around a 1.5X to 3X instead of a 7.5X differential. Unfortunately, looking at things through this lens raises other issues, in that the average mutual fund pays out around 5-7% APR, depending on the health of the entire economy.

Could a savvy investor do any better? Perhaps.

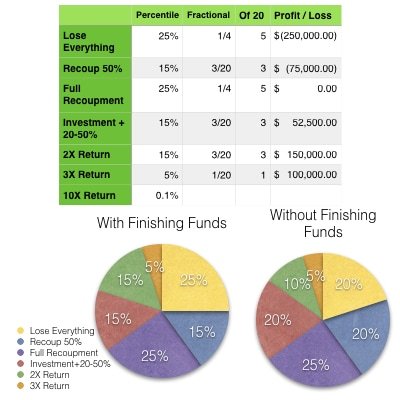

Everything we’ve been looking at so far has assumed that all of these investments were early stage. If it were a tech investment, we’d say Seed or Series A, in film, we’ve been assuming these investments take us out of development and into preproduction. But what if we were to include completion funding and distribution funding in the portfolio? I would do a similar analysis for technology companies, however, given that the VCs and hedge funds dominate that world due to the amount of capital needed. In days and years past, these stages would be overwhelmingly covered by distributors, but that’s nowhere near as true as it used to be. This leaves a hole for an investor to come in and increase their potential returns while lowering their risk exposure.

The assumptions I’ve made on the chart above are that the slate would be made up of half of finishing/distribution funds, and half of the early-stage investments. As such, the risks are far lower, and since much of the later stage debt may be done in the form of debt as opposed to equity, we can assume not a huge amount of loss on those investments. Also, since the film needs to be finished and not made from the start, the time for the recoupment of these funds is greatly lessened. With that in mind, we'll assume that the bulk of these returns come in from 3-4 years instead of 3-5.

I'd like to take this opportunity to remind you that none of this is meant to be scientifically accurate, but rather a very good estimate and approximation of what these slates could look like given the right set of circumstances. Take these numbers with a grain of salt, just as you should any revenue projections from a pre-seed stage startup or revenue projections from a filmmaker. This also should not be considered financial advice, nor a solicitation for sort of funding.

Admittedly, these numbers are highly speculative, [See disclaimer on part 1] but the right team backing up the right filmmakers may make it possible. Given I work with investors, I should state these do not constitute any legal documentation, it’s really just a theoretical exercise to help compare two asset classes. Again, not a solicitation.

By creating a slate investment that includes completion funding as part of the investment mix, we lessen the risk and decrease the time to getting the money back. How does that affect the APR?

With the inclusion of completion funding in a portfolio, the APR of a film slate is looking relatively competitive. If you’re an investor, you may be asking yourself, “Well if it makes that big a difference why not focus only on completion funding?” It’s a great question, there are many funds that do. So many in fact, that the playing field is getting fairly crowded. Especially when you compare it to the other funds that focus on development throughout the film industry.

If a fund only offers completion funding, It would be difficult to establish the long-term relationships with the emerging talent necessary to make an organization like this work. It would also be harder to attract high-end prospects for bigger films with more recognizable names. If a fund does a mixture of the two, it can be a very good way to find new filmmakers and help them pass the goalpost on their first film. Once they’ve done that, you can start to work with them on future projects at an earlier stage. By doing this, the fund creates a better vetting process and attracts higher-end talent.

With that in mind, a mix of investments seems to further the goals of the organization and the industry in a much more cohesive manner. It also starts to sound a lot like Staged Investments, like Seed Stage, Series A, B, C, and the like. Don’t worry, we’ll have a much more in-depth conversation about this later in the series, as well as a couple of other blogs on the site tagged “Staged Financing”

But first, We’re going to talk about some of the excitement associated with both of these types of investment. The Decacorns and Breakouts. That blog can be found below. Again, for legal reasons I need to state that none of this should be considered financial or legal advice, as I am not a lawyer nor a financial advisor. Further, this is not a solicitation for funding or investment.

The only thing I will solicit you to do before finishing up this beast is a blog is to join my mailing list so you can grab my free film business resource package. (segues, eh?) It includes a FREE Deck template to help you talk to the investors you’re probably considering approaching if you’re reading this. It’s also got a free e-book, and other money and time-saving resources. Check it out below.