7 Reasons Courting an Investor is Like Dating

Closing investment for your film is all about your relationship with your investor. It’s weirdly like dating. Here’s why.

There’s an old adage that Investing is like Dating. In fact, I’ve talked about the similarities both on meetings with investors, and dates with people who are qualified to be investors. So as something of a tongue-in-cheek yet still (Mostly) safe-for-work post, here are 7 ways courting an investor is like dating.

1. Your goal is to see how compatible you are with the other person.

Most of the time, if you want to get into bed with someone, you want to be compatible with them first. Getting money from an investor isn’t like a one-night stand. You don’t just get the check and then never hear from them again. Getting into bed with an investor is a long-term deal, so making sure you two work well together is simply a must. Otherwise, the break-up may not be pretty.

2. If you come off as Asking for too much the first time out, you probably won't get a second.

The first time you go out with an investor is kind of like that first coffee date. you’re both sizing each other up, and you want to see how you click. If you went on a first date trying to make out and take the partner back to your place, it’s probably not going to end well for you. Similarly, if you start asking an investor to whip out their checkbook on the first meeting, then you’re not likely to get a call back for a second.

In summation, the goal of your first date should always be to get a second. If you’re out with an investor, then the second meeting is the sole goal of the first meeting.

3. It Generally takes at least 3-5 meetings to jump into bed together.

As with dating, it generally takes 3-5 meetings to decide to get into bed together. Often, the longer it takes the more likely it is that the relationship will be fruitful down the line. At least to a point. If it takes more than 7 meetings to get a check, the investor (or your romantic partner) might just want to be friends.

4. Both Parties have something to gain, but generally speaking one has significantly more options than the other.

Just like women are generally more sought after than men in the dating scene, Investors are generally more sought after than entrepreneurs. This may sound crass, but the only pretty girl in the room is going to get a lot more offers than the 10 guys pursuing her. The ratio is similar for investors.

So sure, while everybody is looking for a mate, and every investor needs deal flow, generally one side has more options than the other. It’s important to remember that when attempting to court an investor.

5. They're Probably going to Google You.

Everybody does diligence in this day and age. If you didn’t think your date was going to check out your online presence, you should probably think again. Investors are going to look into your past history, and maybe even check your credit before they invest in you. Dates will do as much as they can on a similar level, but probably not check your credit.

Related: 5 Steps for Vetting Your Investors

6. If you jump into bed on the first date, you're in for a wild ride. a

One-night stands can be fun and all, but if you jump into bed with the wrong person right after meeting them it can be a real nightmare. (Or so I’ve been told…) If you don’t take the time to get to know somebody before you get into a serious relationship with the, you’re going to be in for a nasty surprise. All investment deals are serious relationships. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

7. When you seal the deal, you might be stuck with that person for YEARS.

If you take money from someone you’ll be dealing with them until all investors somehow exit the company. This can be many years. The Series A Investors at Twitter didn’t exit until their IPO Years later, and a film generally takes 3-5 years to pay back their investors, if they ever do.

If you do get into bed with an angel investor to finance your feature film or web series, they’re going to be a part of your business for a long time. It’s not just about finding independent film angel investors, it’s also about courting them and making sure you’ve found the right investor, not just the first investor who makes you an offer.

If you want some help with this courting process, my free resource package is a great place to start. It’s got a free e-book that might answer some questions your investor may have. It’s also got a deck template you can use in your first meeting. Get it for FREE below.

Check out related content using the tags below.

The 5 Rules to Running a Successful Crowdfunding Campaign

Like it or not, if you want to finance your first feature film, you’re probably going to need to crowdfund part of the budget. Here’s a guide to get you started.

Since my exit from Mutiny Pictures Most of my work, these days is as an executive producer, consultant, distribution representative, and marketer. However, there was a time when I was a filmmaker and a regular (as opposed to executive) producer. During that time, I raised a total of 33,000 on Kickstarter for two projects. This blog gives you some of what I learned from those two campaigns.

While those two projects never went as far as they could have due to a parting of ways between myself and my former business partner, there’s still a lot of information I learned in running these campaigns in the early days of Kickstarter. Here are 5 of them.

#1. Prepare

You CANNOT be successful in crowdfunding without preparation, and that preparation starts early. Generally, your soft preparation for a crowdfunding campaign will start at least 6 months before you launch your campaign. This soft preparation will consist more of being an active member of your community. About 3 months out you’ll need to get ready to shoot your video, and about 2 months later you’ll need to get ready for pre-launch.

I’ll be releasing a preparation timeline in a few weeks, so check back soon!

#2. Grow Your Network

About 80% of your donations will come from people you already know and interact with regularly. This is why you need to become active in communities that will be interested in your film. This can be alumni organizations, groups of people enthusiastic about the kind of film you’re making, and any other group of people that are tangentially connected to the film you’re planning on making.

#3. It’s a Full Time Job, Plan Accordingly

No matter how much preparation you do, when the campaign starts it will be at least one person’s full-time job. You’ll need to personally thank everyone who donates, and you’ll need to spend a lot of time emailing basically everyone you know individually. If you’re smart, you’ll do it twice. Bulk emails aren’t going to do you anywhere near as much good as individual emails, and individual emails take a lot of time.

#4. Try to Get as Much Press as Possible

The best way to add legitimacy to your campaign is to get mentioned in the press. In order to get that press you’ll need to reach out to any editors and reporters you can that might cover you. Note that I say editors and reporters THAT MIGHT COVER YOU. If you know a reporter at Variety, you probably don’t want to email them about your campaign since they’re not going to cover it. If you grew up in a small town with a local paper, you definitely do. You’d be surprised what they’ll cover.

This is something you can work with your prospective crew about as well. Maybe you’re not from a small town, but your DP or production designer might be. This can be a very mutually beneficial arrangement, it puts your crew in the spotlight and raises the profile of the film.

It would be wise to send out a press release via one of the many press release sites. This will help you generate at least a few articles on affiliates for NBC, FOX, and others that you can use to grow the profile and perceived legitimacy of your campaign. It also has some SEO benefits, but I’m not sure that would help too much on crowdfunding.

#5. DON’T SPAM

Don’t post your campaign incessantly on all of your social media, Make sure you continue to provide value outside of asking for money while you’re in your campaign.

If you use Messenger to send your campaign to someone, open up a conversation first. Don’t just copy-paste a form email with no conversation back from them.

Say hello to someone first. Ask how they’re doing. Then send them info about your campaign when they ask what you’re up to. Taking the time to show you care about what’s going on in their life will greatly increase both your conversion rate and the amount each member of your network contributes.

Thanks for reading! If you like this, you should go ahead and grab my FREE Film Market Resource Pack. It’s got a free e-book of articles like this one to help you grow your filmmaking career, free templates to streamline investor and distributor conversations, and even a monthly content digest that helps you continue to grow your knowledge base on a schedule that’’s manageable to almost anyone. Get it for FREE Below.

7 Realistic ways to Find First Money In on your Feature Film.

The first money in is always the hardest to raise. Here’s a guide of realistic sources you can actually raise for your feature film.

When fundraising for anything, the first money is always the hardest. Investors don’t want to be the first in due to the investment seeming untested. So in order for them to feel more secure, you might need to raise some of the money in other places. Here are the 7 most realistic places for filmmakers to go to get first money in.

First money in isn’t meant to be the entirety of your budget. It’s only meant to be about 10%. Having raised 10% of your budget helps investors see that you’re serious, and aren’t going to require them to do all of the funding work themselves. With that in mind, almost every item on this list is not meant to fund your entire movie, but more serve as a jumping-off point to help you raise the funds you need to make an awesome film.

Highly Related: The 9 ways to Finance your Independent Film

1. Donation based Crowdfunding

I know most filmmakers really don’t want to hear about crowdfunding, but it’s still one of the best ways to serve as a proof of concept for a film. It’s also a great way to get first money in. Specifically for this example, I’m talking about donation based crowdfunding. I’m far from an expert in equity crowdfunding, and while there’s potential in the idea, it’s unclear how it should be executed.

That being said, donation based crowdfunding can be an excellent way to get the project rolling, and get further into development.

2. Tax Incentives

Depending on where you’re planning on shooting, Tax incentives can be a great way to get a portion of your funding in place. If you’re in the US, then shooting in Kentucky can get you as much as 35% of your budget. Granted, that will go down to about 30% once you take out a loan against it so that it becomes real money instead of a letter of credit. That loan will be fairly low interest, since Kentucky’s incentive is structured as cash.

There are a lot of things I could go into about tax incentives, but it’s more than I can cover in this blog. I might make a future blog or video about it Comment and ask.

3. Grants

There aren’t a lot of development stage grants out there, and as such the few there are tend to be in very high demand. However, if you can get some portion of you money via a grant from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation or some other development stage granter, then it cuts the risk for your investors and gives you first money in.

Keep in mind, most organizations that give grants turn you down automatically when you first apply. It can be wise to apply multiple years in a row while you try to get this film, or other films off the ground.

4. Equipment Loans

An equipment loan is a relatively low interest loan that uses any equipment you own as collateral for the money that’s being lent. I understand that this is a scary prospect for many filmmakers (With good reason) but it can be a way to get money into the project at an early stage, and serve as your first money in.

It’s also important to note that debts are paid off before equity is paid back, so your loan would be repaid and your equipment secured before any future investor got their money back. Of course, this isn’t always the case, but it generally is.

5. Personal or Business Credit

There are a few people who will loan money for films based on your personal credit. Sometimes it will be a business loan, sometimes it will be an insanely high limit credit card, but in the end it can be the money you need for development. It’s not ideal, but it can be a way to get your movie to the next level.

If you’ve been making corporate videos through your entity for a number of years your business may have enough credibility to take out a moderaate interest loan from a bank against your future corporate video earnings.

In general, this will be a percentage of your previous earnings according to you last few tax returns and whatever debt burden the business has from general operations. This is best used to offset time away from corporate work as an expansion into a new product line, I.E. your feature film.

This would most likely be considered an unsecured loan, which means it’s higher interest than the equipment loan or anything of the sort like that.

If you do go down this road, you should not forget that it often takes 12 to 18 months from delivery to a distributor to start earning royalties, and that’s not accounting for the minimum of 9-12 months to make the film and deliver it to a distributor. The interest over the course of a term like that might be hard to bear.

I should stress I’m not a lawyer or financial advisor. You should check with yours before acting on anything on this list, especially anything that’s debt base.

6. Wealthy Friends and Family

If you’re lucky enough to have accredited investors in your friends and family, then this can be a good way to get your first money in. Investors normally invest in people as much if not more than projects, so approaching someone you already know is generally an easier ask than someone you don’t. Since this blog is about getting first money in, having an investment from a wealthy friend or relative can be the quickest and easiest way to get over that hurdle.

Of course, in order to raise money from wealthy friends and family, you must HAVE wealthy friends and family. If your friends and family ARE NOT Accredited investors, then it’s best to include them in a donation-based crowdfunding round. While the SEC (Securities and Exchanges Commission) has loosened requirements for high-risk and small business investments since the JOBS Act, they’re still very strict when it comes to high risk investments, and it would be better for you to not run afoul of them.

7. Equity Investment

Finally, if you don’t have wealthy friends and family, you can chase equity investment. Normally this means that you would approach the person who owns the car dealerships in your neck of the woods, or other local business leaders. If you can get a meeting to talk to them about investing in a movie, there’s a chance that the excitement of it might help you raise a portion of your funding.

Mind you, this is not an easy sale. It’s going to take a skilled salesperson to pull it off, and a lot of research into why someone like this person who owns the car dealerships would want to invest in your project.

Thank you for reading! If you found this content valuable, check out my FREE film business resource pack. It’s got a free e-book on the indiefilm biz featuring 21 articles around similar issues covered in my blog. Around half of those articles can’t be found anywhere else. Additionally, you’ll get an indiefilm deck template you can use to create a deck for investors, contact tracking templates, form letters, and a whole lot more! Check it out below.

The 9 Ways to Finance an Indiependent Film

There’s more than one way to finance an independent film. It’s not all about finding investors. Here’s a breakdown of alternative indie film funding sources.

A lot of Filmmakers are only concerned with finding investors for their projects. While films require money to be made well, there’s are better ways to find that money than convincing a rich person to part with a few hundred thousand dollars. Even if you are able to get an angel investor (or a few ) on board, it’s often not in your best interest to raise your budget solely from private equity, as the more you raise the less likely it is you’ll ever see money from the back end of your project.

Would you Rather Watch or Listen than Read? I made a video on this topic for my YouTube Channel.

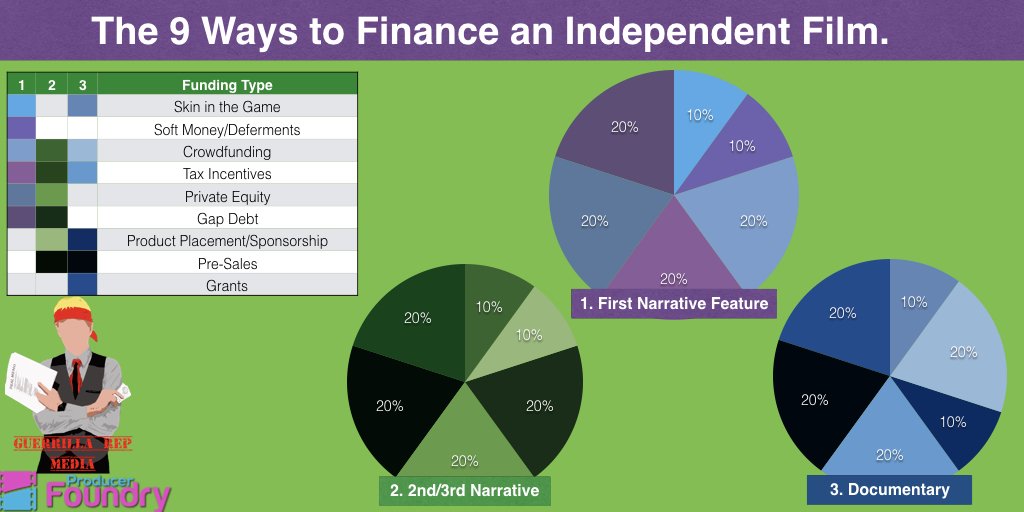

So here’s a very top-level guide to how you may want to structure your financial mix. The mixes in the image above loosely correspond to the financial mix of a first-time film, a tested filmmaker’s film, and a documentary. They’re also loose guidelines, and by no means apply to every situation, and should not be considered financial or legal advice under any circumstance. This is just the general experience of one Executive producer.

Piece 1 — Skin in the game. 10–20%

Investors want you to be risking something other than your time. The theory is that it makes you more likely to be responsible with their money if you put some of yours at risk. This can be from friends and family, but they prefer it come directly from your pocket.

I've gotten a lot of flack for this. However, the fact investors want skin in the game is true for any industry or any business. Tech companies normally have skin in the game from the founders as well, not just time, code, or intellectual property.

However, if you’ve got a mountain of student debt and no rich relatives, then there is another way…

Piece 2 — Crowdfunding 10–20%

I know filmmakers don’t like hearing that they’ll need to crowdfund. I understand it’s not an easy thing to do. I’ve raised some money on Kickstarter and can verify that It’s a full-time job during the campaign if you want to do it successfully. However, if you can hit your goal, not only will you be able to put some skin in the game, and retain more creative control and more of the back end but you’ll also provide verifiable proof that there’s a market for you and your work. Investors look very kindly on this.

That said, just as success provides strong market validation as a proof of concept, failing to raise your funding can also be seen as a failure of concept. and make it more difficult to raise than it would otherwise have been. Make sure you only bite off what you can chew.

Due to the difficulty in finding money for an independent film, the skin in the game or crowdfunding portion of the raise for a director’s first project is often a much higher percentage of the raise than it will be for their future projects.

Piece 3 — Equity 20–40%

Next up is equity. This is when an investor gives you money in return for an ownership stake in the company. From a filmmaker's perspective, it’s good in that if everything goes tits up, you don’t owe the investors their money back. Don't misunderstand what I mean by this. You ABSOLUTELY have a fiduciary responsibility to do your due diligence and act in the best interest of your investors to do absolutely everything in your power to make it so they recoup their investment. If you do that, or if you commit fraud, your investors can and likely will sue the pants off of you. You’ll have an uphill battle on that as well since they probably have more money for legal fees than you do.

Also, you will need a lawyer to help you draft a PPM. You shouldn't raise any kind of money on this list without a lawyer, with the possible exception of donation-based crowdfunding or grants. In general, just remember that I’m a dude who produced a bunch of movies who writes blogs and makes videos on the internet. Not a lawyer or financial advisor. #Notlegaladvice #Notfinancialdvice #mylawyermakesmewritethesesnippets.

It’s bad in that if everything goes extremely well, they get a huge percentage of your film. So it deserves a place in your financial mix, but ideally a small one.

For a longer list of my feelings on this topic, check out Why film needs Venture Capital, or One Simple Tool to Reopen Conversations with Investors

Piece 4 — Product Placement 10–20%

Product placement is when you get a brand to compensate you for including their product in your film. It’s more common in the form of donations or loans for use than hard money, but both can happen with talent and assured distribution. If you’re a first-timer, it’s difficult to get anything other than donated or loaned products.

Piece 5 — Presale Backed Debt 0–20%

Everything you read tells you the presale market has dried up. To a certain degree, that is true. However, it’s more convoluted than you may think. According to Jonathan Wolfe of the American Film Market, the presale market has a tendency to ebb and flow with the rise and fall of private equity in the filmmaking marketplace. There’s been a glut of equity for the past several years that’s quickly drying up.

That said, there are a lot of other factors that will determine where pre-sales end up in a few years. The form has shifted, in that it’s generally reputable sales agents that give the letters instead of buyers and territorial distributors. You then take that letter to a bank where you can borrow against it at a relatively low rate.

Piece 6 — Tax incentives 10%-20%

While many states have cut their filmmaking tax incentives, it’s still a very viable way to cover some of the costs of making your project. It is worth noting that the tax incentive money is generally given as a letter of credit, which you can then borrow against or sell to a brokerage agency. It’s not just a check from the state or country you’re shooting in. This system of finance is significantly more viable in Europe than it is in the US, but no matter where you plan on shooting it needs to be part of your financial mix.

Piece 7 — Grants 0–20%

There are still filmmaking grants that can help you to make your project. However, that’s not something that is available to all filmmakers, especially when they’re first making their projects. Don’t think grants don’t exist for you and your project, because they probably do, spend an afternoon googling it. My friend Joanne Butcher of www.FilmmakerSuccess.com suggests applying for one grand a month for the indefinite future, as when you do so you’ll develop relationships with the foundations you contact which can be invaluable for your career growth.

Grants are much easier to get as a completion fund once you’ve shot your film. Additionally, films made overseas are more likely to be funded by grants than those shot here in the US.

Piece 8 — Gap/Unsecured Debt 10–40%

Gap debt is an unsecured loan used to create a film or television series. This means that the loan has no collateral, be it product placement, Presale, or tax incentive. It used to be handled by entertainment banks for a very high interest rate, I can’t say who my source was on this, but I have heard of interest rates in excess of 50% APR. That market has been largely taken over by private investors loaning money through slated, which did bring interest rates down. Unsecured debt almost certainly requires a completion bond, which generally means that it’s only suitable for projects over 1mm USD in budget.

In general, you should use this form of financing as little as possible, and pay it back as quickly as possible. Again, Not legal or financial advice.

Piece 9 — Soft money and Deferments — whatever you can

Soft money is funding that isn’t given as cash. This can be your crew taking deferred payment for their services, or receiving donated or loaned products, locations, and anything else meant to get your film made. This isn’t so much funding as cost-cutting. It often includes donations or loans from product placement.

If you like this content and want to learn more about film financing, you should consider signing up for my mailing list. Not only will you a free e-book, but you’ll also get a free deck template, contract tracking templates, and form letters. Plus you’ll stay in the know about content, services, and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media.

Can a Film Slate Make More than a Tech Portfolio?

Most people know film is a bad investment. There is one potential saving grace though.

Edit from the future: Maybe, but probably not, and don’t count on it.

In a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, “The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.” He also called it “The 8th wonder of the world, he who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t pays it.” In this post, we’re going to be examining how we can use the notion of compound interest in comparison to tech and film investments.

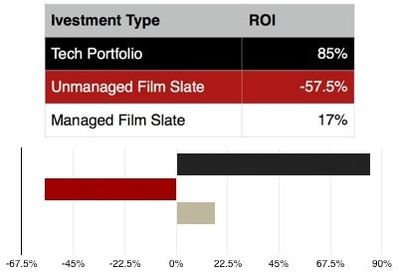

In the previous installment, we looked at the average ROI of a film slate vs. an early stage tech portfolio. Here’s what we came up with before. For the full tables and Metrology, check out last week’s post.

Unfortunately, the numbers don’t look good for film. By the math above, we can see that tech portfolios make on average of 7.5X what a film slate would over their lifespans.

But, film does have one advantage over tech. The amount of time that it takes for a film to recoup [if it’s going to] is much shorter than what it would take for a tech exit would be.

For instance, the average time from when an Angel becomes involved in a project to when they see their money back is around 12 years. For a film to at least start recouping investment, that time period is around 2-3 years, if it’s done well and distribution is planned from the beginning.

Why is that? Generally, for a tech investor to get their money back, the company they invested in has to either be acquired by a larger company or make an initial public offering [IPO] and be listed on a stock exchange. Sometimes an investor will be able to list their stock on a secondary exchange, but that’s a little beyond the scope of this article. Acquisitions tend to happen more quickly than IPOs, but there’s generally less money and less prestige.

Given that the size of venture capital [as opposed to angel investment] rounds have ballooned in the last decade, many venture capital firms are pushing their companies to IPO instead of be acquired. This may make the time from an early round angel investment to exit take even longer than the 12 years mentioned above.

Films, on the other hand, start getting some of their money back shortly after they start distributing the film. If the filmmakers get a minimum guarantee [MG] they may get a decent check up front. If they don’t, they may not, and it may take an additional year or so to start getting their money back. I should note MGs are more the exception than the rule.

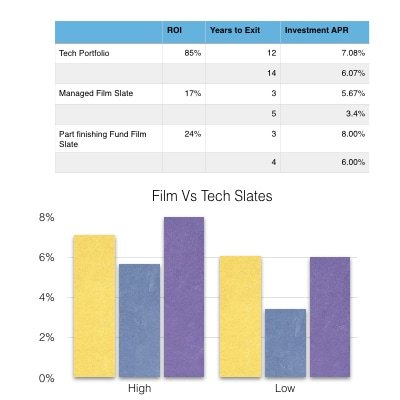

So for this exercise, we’re going to look at the APR of both a technology investment portfolio and a film slate. We’re going to make the assumption that both investments are early stage, since the angel round for a technology company is very early in the investment process, generally directly after the friends and family round. Later rounds are generally dominated by institutional investment firms. A similar scenario can be said about film. Most angels from other industries get involved very early, since they don’t have contacts with completed projects.

Since revenue from a film tends to come in over time, we’ll count the lifespan of a film investment to be 3-5 years as opposed to the 2-3 years mentioned above. 3-5 years should be enough time for 60-80% of a films total revenue to come in on average. As such, since this series is largely a thought experiment we’re going to think the general earnings of a film to come in overt that shortened timeframe. Tech exits on the other hand generally come with a large lump sum for the investor after a quite a long time that may be getting longer, we’re going to do the math based on 12-14 years to exit for a tech company. Some do come in much faster, but some films also get bought out for millions after 18 months. They’re outliers and not generally worth accounting for when planning to pitch an investor.

Tech portfolio APR

When we compare APRs, this is starting to look a little more reasonable, but still not great. When we compare the APR of a film as opposed to a technology company, we’re only looking at around a 1.5X to 3X instead of a 7.5X differential. Unfortunately, looking at things through this lens raises other issues, in that the average mutual fund pays out around 5-7% APR, depending on the health of the entire economy.

Could a savvy investor do any better? Perhaps.

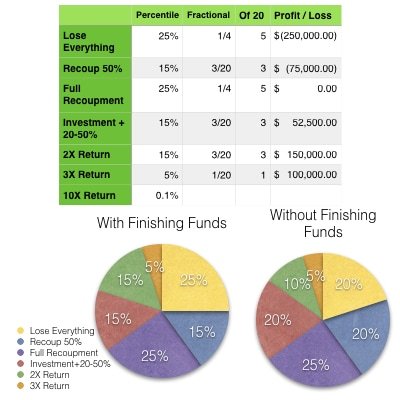

Everything we’ve been looking at so far has assumed that all of these investments were early stage. If it were a tech investment, we’d say Seed or Series A, in film, we’ve been assuming these investments take us out of development and into preproduction. But what if we were to include completion funding and distribution funding in the portfolio? I would do a similar analysis for technology companies, however, given that the VCs and hedge funds dominate that world due to the amount of capital needed. In days and years past, these stages would be overwhelmingly covered by distributors, but that’s nowhere near as true as it used to be. This leaves a hole for an investor to come in and increase their potential returns while lowering their risk exposure.

The assumptions I’ve made on the chart above are that the slate would be made up of half of finishing/distribution funds, and half of the early-stage investments. As such, the risks are far lower, and since much of the later stage debt may be done in the form of debt as opposed to equity, we can assume not a huge amount of loss on those investments. Also, since the film needs to be finished and not made from the start, the time for the recoupment of these funds is greatly lessened. With that in mind, we'll assume that the bulk of these returns come in from 3-4 years instead of 3-5.

I'd like to take this opportunity to remind you that none of this is meant to be scientifically accurate, but rather a very good estimate and approximation of what these slates could look like given the right set of circumstances. Take these numbers with a grain of salt, just as you should any revenue projections from a pre-seed stage startup or revenue projections from a filmmaker. This also should not be considered financial advice, nor a solicitation for sort of funding.

Admittedly, these numbers are highly speculative, [See disclaimer on part 1] but the right team backing up the right filmmakers may make it possible. Given I work with investors, I should state these do not constitute any legal documentation, it’s really just a theoretical exercise to help compare two asset classes. Again, not a solicitation.

By creating a slate investment that includes completion funding as part of the investment mix, we lessen the risk and decrease the time to getting the money back. How does that affect the APR?

With the inclusion of completion funding in a portfolio, the APR of a film slate is looking relatively competitive. If you’re an investor, you may be asking yourself, “Well if it makes that big a difference why not focus only on completion funding?” It’s a great question, there are many funds that do. So many in fact, that the playing field is getting fairly crowded. Especially when you compare it to the other funds that focus on development throughout the film industry.

If a fund only offers completion funding, It would be difficult to establish the long-term relationships with the emerging talent necessary to make an organization like this work. It would also be harder to attract high-end prospects for bigger films with more recognizable names. If a fund does a mixture of the two, it can be a very good way to find new filmmakers and help them pass the goalpost on their first film. Once they’ve done that, you can start to work with them on future projects at an earlier stage. By doing this, the fund creates a better vetting process and attracts higher-end talent.

With that in mind, a mix of investments seems to further the goals of the organization and the industry in a much more cohesive manner. It also starts to sound a lot like Staged Investments, like Seed Stage, Series A, B, C, and the like. Don’t worry, we’ll have a much more in-depth conversation about this later in the series, as well as a couple of other blogs on the site tagged “Staged Financing”

But first, We’re going to talk about some of the excitement associated with both of these types of investment. The Decacorns and Breakouts. That blog can be found below. Again, for legal reasons I need to state that none of this should be considered financial or legal advice, as I am not a lawyer nor a financial advisor. Further, this is not a solicitation for funding or investment.

The only thing I will solicit you to do before finishing up this beast is a blog is to join my mailing list so you can grab my free film business resource package. (segues, eh?) It includes a FREE Deck template to help you talk to the investors you’re probably considering approaching if you’re reading this. It’s also got a free e-book, and other money and time-saving resources. Check it out below.

Why Film Needs Venture Capital

Part of creating a sustainable revolution in the film industry is creating a new system of finance. For that, we should look to other industries starting with Private Equity and Venture Capital. Here’s how we do that.

A lightbulb next to a chart outlining the allocation of venture funds in 2011 above a text blurb outlining the data source.

There’s an old joke that goes something like this. Three artists move to Los Angeles, a Fine Artist, a poet, and a Filmmaker. The first day they’re in town, they check out the Mann’s Chinese Theater. When they get there, a wave of inspiration overtakes them. The fine artist says, “This is incredible, I have to draw something! Does anyone have a piece of chalk?” Low and behold a random passerby happens to have one, and hands it over. The fine artist does a beautiful rendering on the sidewalk.

Watching this, the poet says, “I’ve had a flash of inspiration, I must write! Does anyone have a pen and paper?” It happens to be a friendly sort of Los Angeles day, and someone hands over a pen and paper. He writes a beautiful Shakespearean sonnet about his friend’s artistry with the chalk.

The filmmaker says “This is amazing, I’ve got to make a movie about it! Does anyone have any money?”

Even though the costs of making a film have been cut drastically, the joke remains true. I mentioned in my last post that the film world is in need of new money, and that what the film world really needs is something akin to Venture Capital. I think the topic deserves more exploration than a couple paragraphs in a post about transparency.

Venture capitalists bring far more than money to the table. They also bring connections and a vast knowledge of financial and industry specific business knowledge to the table. Essentially these people are experts at building companies, and when you really break it down the best films really are just companies creating a product.

The contribution of connections and knowledge is just as vital to the success of the startup as the money is. We have something somewhat similar in the film world, it’s generally the job of the executive producer to find the money for the film and put the right people in place to run the production and complete the product.

The biggest problem is that good executive producers with contact to money are few and far between, and there are very few connection points between the big money hubs and the independent film world. Filmmakers often don’t only need money, they need to have an understanding of distribution and finance that many simply do not have, and most film schools just do not teach. These positions are generally not full time positions, and most filmmakers just don’t have the money they need to pay people like this. If a venture capital model were to be adapted in film, the firm could link to these experts, and included in the budget for the film at a cost far less than it would normally be, because the person could split their time between all of the projects represented by the firm.

Most people understand that filmmakers need money, what many people do not understand is that there are very valid reasons for an investor to invest in film.A good investor knows that a diverse portfolio is far better than one that focuses solely on one industry. Industries can change and the revenue brought in by any single industry can crash with little notice. Savvy investors will seek to have money in many pots as it really helps to weather through downturns. Film is considered to be a mature industry, and has grown steadily over the past several years, even in the economic downturn. In fact, the film industry is moderately reversely dependent on the economy, so it often does better in economic downturns.

The biggest problem is that most investors just don’t invest in things they don’t know. Investors need to understand an investment before they put money into it.

Film is a highly specialized and inherently risky business. All the money goes away before any comes back, and that can scare off many investors. Especially since they often don’t understand what a good use of resources for a film is and are often incapable of seeing when the project should be stop-lossed as to not lose any more money.

One solution a venture capital firm could bring to this industry that single investors simply cannot is stage financing. Stage financing is a system of finance that is widely used in Silicon Valley. The concept is basically that the investors only release funds once certain checkpoints are met. Single angel investors do not have the time or expertise to act in this way, which is a big part of the reason for the standard escrow model. If a project that makes it through the screening process is only given the money they need for pre production up front, they must pass a review to have funds released for principle photography then it becomes a far more sustainable investment.

Filmmakers may balk at the idea of review, but quite frankly so long as the production is being well managed, they should be able to complete the checkpoints and have the additional funds released with little difficulty, assuming that the right review panel is put in place. The fund itself has every reason to see it’s projects through to completion, so it will only be filmmakers who are not doing their jobs that end up not passing the review process.

Edit: Additionally, there are deals that can be made to help agents and bankable talent feel more comfortable with such a process. This may be a subject of a later blog, and is mentioned in the comments.

Why does the fund have every reason to see films through to completion? Because if the films are not completed, then the fund will have lost all the money it put in with no chance of getting it back. That said, if the production is a disaster, and it’s clear that additional funds would not actually result in a finished and marketable film, then it is far better to cut losses and move on with other projects that have higher potential for revenue.

As mentioned in the last blog, a lack of transparent accounting is also a big issue with investors.

A single filmmaker does not really have the ability to negotiate with a distributor, at least not to a level necessary to resolve the transparency issue. In the relationship, the distributor has all of the power and there’s really very little most filmmakers, especially those just starting out, can do to change that.

But in film as in any industry, money talks. If there were a venture capital firm for film that only worked with distributors who have transparent books, and those distributors could then turn around and propose new projects to the venture capital firm, then some of the issues of transparent accounting could start to change. Many distributors, especially those working in the low budget sphere, are continually raising money for their own projects. So, having a good relationship with a venture capital firm is a big incentive to maintain good books and responsible business practices for filmmakers.

It got listed in the comments section of Black Box that filmmakers shouldn’t necessarily need to have that much business sense, since it takes their whole being to create. Filmmaking is indeed a collaborative effort, and it’s not a director’s job to think about target demographics and marketing strategies. The problem is the people in the film world that truly understand investment and recoupment are few and far between. Many of them also take advantage of filmmakers, as evidenced by the stories of studio accounting from Black Box. Part of what’s needed is the creation of teams that have what it takes to both tell quality stories with high production values, also get the films to market and figure out exit strategies, target demographics, and general budget recoupment tactics.

Many Film Schools just don’t teach this part of the business. Film schools focus everything on how you can make the film, and what it takes to do it, but few of them really give you the ability to actually go raise money. So what’s really needed is a new class of producer that understands the executive side. What’s really needed is a new class of investor that understands what it takes to invest in film, the risks, the rewards, and how it’s diversified. What’s really needed in film is a company that can successfully link the two together, and create a new class of media entrepreneur. What’s really needed is an incubator for independent film with a team that can execute both of these aspects and create a sustainable business model out of it.

Right now no such organization really exists. Legion M has some elements of it, but they miss the new talent discovery elements in favor of risk abatement. Slated works similar to AngelList, but I’m not sure their track record is what it needs to be to justify their price point. I’ve been trying to start one between my various projects with angel groups, Mutiny Pictures, Producer Foundry, and other ventures. It’s clear that the industry is changing, but quite frankly it needs to. The best way to effect the change in practices that need to happen in the industry is to change the way the industry is financed. The entrance of a film fund that operates on principles more akin to the aspiraations of a venture capital firm would do just that, and is exactly why it needs to happen.

If you enjoyed this blog, please share it to your social media. You should also join my mailing list for some curated monthly blog digests built around categories like financing, investment, distribution, marketing, and more. As well as some templates (including a deck template) as well as other discounts, templates, and other resources.