Can a Film Slate Make More than a Tech Portfolio?

Most people know film is a bad investment. There is one potential saving grace though.

Edit from the future: Maybe, but probably not, and don’t count on it.

In a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, “The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.” He also called it “The 8th wonder of the world, he who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t pays it.” In this post, we’re going to be examining how we can use the notion of compound interest in comparison to tech and film investments.

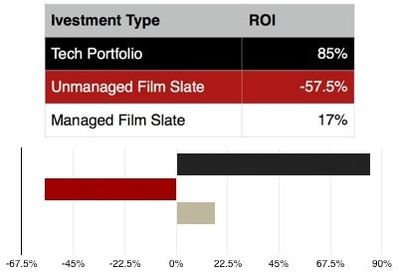

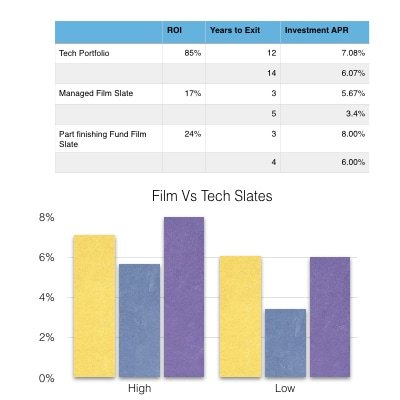

In the previous installment, we looked at the average ROI of a film slate vs. an early stage tech portfolio. Here’s what we came up with before. For the full tables and Metrology, check out last week’s post.

Unfortunately, the numbers don’t look good for film. By the math above, we can see that tech portfolios make on average of 7.5X what a film slate would over their lifespans.

But, film does have one advantage over tech. The amount of time that it takes for a film to recoup [if it’s going to] is much shorter than what it would take for a tech exit would be.

For instance, the average time from when an Angel becomes involved in a project to when they see their money back is around 12 years. For a film to at least start recouping investment, that time period is around 2-3 years, if it’s done well and distribution is planned from the beginning.

Why is that? Generally, for a tech investor to get their money back, the company they invested in has to either be acquired by a larger company or make an initial public offering [IPO] and be listed on a stock exchange. Sometimes an investor will be able to list their stock on a secondary exchange, but that’s a little beyond the scope of this article. Acquisitions tend to happen more quickly than IPOs, but there’s generally less money and less prestige.

Given that the size of venture capital [as opposed to angel investment] rounds have ballooned in the last decade, many venture capital firms are pushing their companies to IPO instead of be acquired. This may make the time from an early round angel investment to exit take even longer than the 12 years mentioned above.

Films, on the other hand, start getting some of their money back shortly after they start distributing the film. If the filmmakers get a minimum guarantee [MG] they may get a decent check up front. If they don’t, they may not, and it may take an additional year or so to start getting their money back. I should note MGs are more the exception than the rule.

So for this exercise, we’re going to look at the APR of both a technology investment portfolio and a film slate. We’re going to make the assumption that both investments are early stage, since the angel round for a technology company is very early in the investment process, generally directly after the friends and family round. Later rounds are generally dominated by institutional investment firms. A similar scenario can be said about film. Most angels from other industries get involved very early, since they don’t have contacts with completed projects.

Since revenue from a film tends to come in over time, we’ll count the lifespan of a film investment to be 3-5 years as opposed to the 2-3 years mentioned above. 3-5 years should be enough time for 60-80% of a films total revenue to come in on average. As such, since this series is largely a thought experiment we’re going to think the general earnings of a film to come in overt that shortened timeframe. Tech exits on the other hand generally come with a large lump sum for the investor after a quite a long time that may be getting longer, we’re going to do the math based on 12-14 years to exit for a tech company. Some do come in much faster, but some films also get bought out for millions after 18 months. They’re outliers and not generally worth accounting for when planning to pitch an investor.

Tech portfolio APR

When we compare APRs, this is starting to look a little more reasonable, but still not great. When we compare the APR of a film as opposed to a technology company, we’re only looking at around a 1.5X to 3X instead of a 7.5X differential. Unfortunately, looking at things through this lens raises other issues, in that the average mutual fund pays out around 5-7% APR, depending on the health of the entire economy.

Could a savvy investor do any better? Perhaps.

Everything we’ve been looking at so far has assumed that all of these investments were early stage. If it were a tech investment, we’d say Seed or Series A, in film, we’ve been assuming these investments take us out of development and into preproduction. But what if we were to include completion funding and distribution funding in the portfolio? I would do a similar analysis for technology companies, however, given that the VCs and hedge funds dominate that world due to the amount of capital needed. In days and years past, these stages would be overwhelmingly covered by distributors, but that’s nowhere near as true as it used to be. This leaves a hole for an investor to come in and increase their potential returns while lowering their risk exposure.

The assumptions I’ve made on the chart above are that the slate would be made up of half of finishing/distribution funds, and half of the early-stage investments. As such, the risks are far lower, and since much of the later stage debt may be done in the form of debt as opposed to equity, we can assume not a huge amount of loss on those investments. Also, since the film needs to be finished and not made from the start, the time for the recoupment of these funds is greatly lessened. With that in mind, we'll assume that the bulk of these returns come in from 3-4 years instead of 3-5.

I'd like to take this opportunity to remind you that none of this is meant to be scientifically accurate, but rather a very good estimate and approximation of what these slates could look like given the right set of circumstances. Take these numbers with a grain of salt, just as you should any revenue projections from a pre-seed stage startup or revenue projections from a filmmaker. This also should not be considered financial advice, nor a solicitation for sort of funding.

Admittedly, these numbers are highly speculative, [See disclaimer on part 1] but the right team backing up the right filmmakers may make it possible. Given I work with investors, I should state these do not constitute any legal documentation, it’s really just a theoretical exercise to help compare two asset classes. Again, not a solicitation.

By creating a slate investment that includes completion funding as part of the investment mix, we lessen the risk and decrease the time to getting the money back. How does that affect the APR?

With the inclusion of completion funding in a portfolio, the APR of a film slate is looking relatively competitive. If you’re an investor, you may be asking yourself, “Well if it makes that big a difference why not focus only on completion funding?” It’s a great question, there are many funds that do. So many in fact, that the playing field is getting fairly crowded. Especially when you compare it to the other funds that focus on development throughout the film industry.

If a fund only offers completion funding, It would be difficult to establish the long-term relationships with the emerging talent necessary to make an organization like this work. It would also be harder to attract high-end prospects for bigger films with more recognizable names. If a fund does a mixture of the two, it can be a very good way to find new filmmakers and help them pass the goalpost on their first film. Once they’ve done that, you can start to work with them on future projects at an earlier stage. By doing this, the fund creates a better vetting process and attracts higher-end talent.

With that in mind, a mix of investments seems to further the goals of the organization and the industry in a much more cohesive manner. It also starts to sound a lot like Staged Investments, like Seed Stage, Series A, B, C, and the like. Don’t worry, we’ll have a much more in-depth conversation about this later in the series, as well as a couple of other blogs on the site tagged “Staged Financing”

But first, We’re going to talk about some of the excitement associated with both of these types of investment. The Decacorns and Breakouts. That blog can be found below. Again, for legal reasons I need to state that none of this should be considered financial or legal advice, as I am not a lawyer nor a financial advisor. Further, this is not a solicitation for funding or investment.

The only thing I will solicit you to do before finishing up this beast is a blog is to join my mailing list so you can grab my free film business resource package. (segues, eh?) It includes a FREE Deck template to help you talk to the investors you’re probably considering approaching if you’re reading this. It’s also got a free e-book, and other money and time-saving resources. Check it out below.

Why Angels Invest and Why they Choose Tech

Most Filmmakers need Investors to make their movies. To convince an investor to back in your indiefilm, you need to understand why they invest in anything,

Why should those Rich Tech [People] Invest in your Film, Part 2/7

In order to understand why an investor should invest in your film, you need to understand why investors invest at all. What is an angel investor? What does it take to be a successful angel investor? Why don’t they just buy that Second Third yacht?

To answer the first question, an angel investor is person of means, who generally has a sizable amount of liquid assets and wants to do something more interesting and potentially lucrative than buying stocks or mutual funds. In order to be an accredited investor, an unmarried person must have made at least 200,000 USD for two consecutive years, and be likely to do the same in the current year. If they’re married, that number is more like 300,000 USD. They could also have 1,000,000 in liquid assets, not including their primary residence.

The reason this came about was to protect individuals from being taken by scam artists. The theory behind the income threshold is that if you’re that affluent, you would either have the education or sense to know if you’re being taken, or the means to hire someone who does.

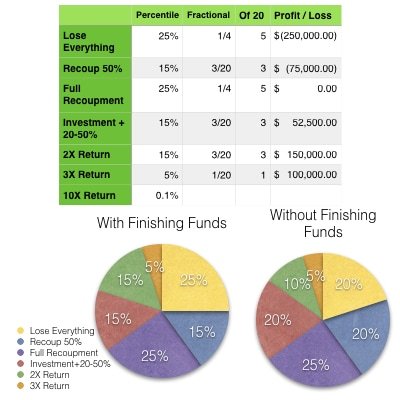

Apart from the aforementioned asset requirement, what does it take to be a professional angel investor? It basically requires two things. Access to capital and deal flow. In layman’s terms, money to invest and projects to invest in. Most of the time, Investors generally assume that about half of their investments will tank and they’ll lose everything due to an inability of the company to exit.

So why do Angel Investors invest? This question is more difficult to answer and actually has several answers that we’ll explore throughout this blog series. But, essentially it boils down to the fact that These investments have the potential to breakout in a big way.

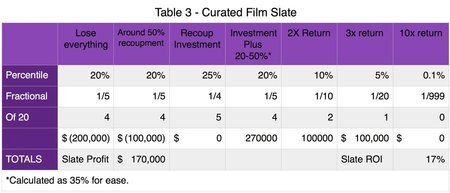

Below is a chart illustrating that point. It has been simplified and assumes very early-stage investments. This chart is generally based on loose feelings and assumptions asserted by many investors I’ve talked to. Just like it’s very difficult to estimate how many films break out, it’s very difficult to estimate how many investments are completely lost. It’s very easy to track winning bets, but much harder to track losing ones. This data is accurate to the dozens of investors I know as to their top-level assumption and the data around films is accurate to my experience as a distributor.

Before we get into any numbers, I should preface I’m not a financial advisor, this is not financial advice, nor am I soliciting for any particular project. This is all conjecture and an extrapolation and explanation of personal experience.

If you’re a filmmaker reading this, you might be thinking to yourself, why are they hunting mythical horses and WTF is a decacorn? A Unicorn is a company valued at more than 1 billion before exiting. If you’re a decacorn, your company is valued at more that 10 billion prior to exit. The reason that you don’t really see it on that pie chart is that it’s only about 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000 chance of happening.

So how do investors get their money back from a tech investment? in order for a tech investor to get their money back, generally the company has to be acquired, or go public [IPO.] Films on the other hand, simply need to find profitable distribution, or self-distribute the product. Each exit in each sector have its pros and cons, but in the end the boils down to which is more accessible. So what does the return look like in both cases?

Let's assume an investor invested One Million Dollars across 20 tech sector investments, each investment is made equally. I know that these tables are going to be hard to fully understand, so I’ll have a better data visualizations after table 3.

As you can see the overall ROI is about 85%, which means they nearly doubled their money on the entire portfolio. This is assuming that the investor isn’t completely green and has some idea of what they’re doing, so they make better picks. At some level, this looks very similar to the studio tentpole system. Experts making bets are confident that the ones that hit will cover the losses of the ones that miss. Unfortunately, the numbers don't back that up in the way we would like, partly due to the fact that most angels in the film stlate are not experts, and many filmmakers don't package as well as they should to maximize potential returns.

What does the picture look like for the investor going with no real knowledge of film look like? Well, from my more than a decade marketing and distributing features, here’s about how that would break out.

That’s not Pretty, but it is making a fair amount of negative assumptions about the slate of films. These numbers are assuming they don’t have distribution going in, don’t know what sells, and the film is financed entirely by private equity. The hypothetical investor made the investment at the outset of the project assuming the entirety of the risk. AND the film isn’t well cast with an eye for international sales.

BUT, if you structure your slate look to get at least a letter of intent for distribution a North American distributor and work with an international sales company to ensure the best casting for international saleability. It’s at least possible that you could have a slate that looks more like this.

That’s better, but a well-managed tech portfolio still obliterates it if we go solely by total return potential. The Graph I mentioned is below, to help illustrate my point. Trying to convince a tech investor to break from what they know to invest in something that has less potential to return is a hard sell.

Edit From the Website Transfer: If I were to re-do this, I would probably put the 10x return at more like 0.5-1% as opposed to 0.1%, assuming we account for one in 10 portfolios of 20 films gets a breakout hit, the potential average returns end up around 20-22% depending on which of the pool the breakout comes from. if 2 out of 10 of the portfolios happen to have a breakout it’s closer to an average return of 24-26%

Filmmakers, this is what you’re up against. But fear not, you may have an ace in the hole. In fact you may have more than one. The first ace in the whole is the speed of exit for film projects compared to that of tech startups. Due to that, film projects can return money to the investor faster than a startup would, which matters significantly in increasing the ability for an investor to re-invest and increasing the overall Annual Percentage Rate (or APR) of the investment. Check out part 3 linked below for more information on that.

Part 1:

Why Don’t those “Rich Tech [People]” invest in Your Film?

Part 2: (This Part)

Why Angels Invest, and Why they Choose Tech.

Part 3:

Examining APR: How does Film Stack up to Tech Portfolios?

Part 4:

Breakouts vs Decacorns

Part 5:

Diversification and Soft Incentives.

Part 6:

What’s really stopping Tech Investors from investing in Film?

Part 7:

How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Thanks for Reading! The numbers in this blog have evolved since I wrote it, but only slightly. If you want to stay up to date on resources, livestreams, and other awesome content I have to offer, you should join my mailing list! You’ll stay up to date on all of my latest content, plus get a free e-book, monthly blog digests, and even a great resource package to help you talk to investors about your film. It’s totally free, so what are you waiting for?

Why Should Those Rich Tech [People] Invest in your Film? [1/7]

Filmmakers often wonder why Investors don’t view film a serious potential investment. This 7 part blog series seeks to answer that question.

I recently went to an event here in San Francisco aimed at bringing together the more established filmmakers in San Francisco to build a better ecosystem for the industry up here. It’s a wonderful idea, a fantastic group of people, and the energy in the room was electric. However, there was one question that kept coming up that filmmakers had a lot of trouble understanding. Why won’t those rich tech people give us money?

This is something that I hear not only in the bay area. There’s a large contingent of Filmmakers in LA or elsewhere that would like to tap into Silicon Valley investment. The trouble is that the perception of film is that it's just a way to lose a lot of money. There are those of us looking to change that perception, however filmmakers need to understand that the overall potential for return is dwarfed when compared to other sectors. Whether that perception is true may be another matter.

This blog is not to disparage mean to discourage you, but to help you better understand the reality of your position. Understanding your position is key to obtaining your objective. To quote the Art of War…

In order to better understand the position of a tech investor, we need to look at how and why generally invest. As an entrepreneur who’s worked in both film and tech, an organizer of many film investment events, and a consultant who helps vet business plans for viability, I’m in a somewhat unique position to help answer that question. So I’m making this a series of 7 posts regarding every aspect of why a Tech investor would invest in a film.

I should clarify that this project is already a little bigger than I anticipated when I started writing it, so it’s going to be largely focused on Tech investment as opposed to sponsorship or any other sort of tech money entering film. I’ll be releasing them weekly, so check back every Wednesday. This post is to serve as a sort of landing page so you can look at all of the different aspects of why a tech investor would invest in a project. I’ll keep this updated, but here’s a loose table of contents that will eventually be linked. In the meantime, check out these other great resources. From me, Producer Foundry, and ProductionNext.

I should stress that the numbers found throughout these articles are inherently speculative, and largely from personal experience, and generalized research. Due to the fact that it’s only really possible to find data on the films and companies that made a return, estimating those that didn’t involve not a small amount of educated guesswork. Generally, the estimates in wins vs losses for films are based on personal experience in distribution, coupled with research and data from sites like IMDb Pro and The-Numbers.com. Tech portfolios are generalized based on research coupled with talks with several professional investors.

In short, these numbers are not meant to be scientific, but more some of the best analyses on this topic you’ll find online for free. If you have any thoughts or issues with these numbers, please feel free to comment below. I’d love an active thread, and I will monitor as much as time permits.

Here’s a handy dandy table of contents for your reference.

Part 2:

Why Angels Invest, and Why they Choose Tech.

Part 3:

Examining APR: How does Film Stack up to Tech Portfolios?

Part 4:

Breakouts vs Decacorns

Part 5:

Diversification and Soft Incentives.

Part 6:

What’s really stopping Tech Investors from investing in Film?

Part 7:

How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

If you liked this, you should check out my FREE Film Markets Resources pack. It’s got lots of things you’ll need to make talk to those rich tech people about your film, including a deck template, form letters, and even a free E-book called The Entrepreneurial Producer. Link below.

If this is all a bit much, and you need more individual attention, check out the guerrilla Rep Media Services page.

Check out the tags below for more related content

The 7 Best Indiefilm (or Entrepreneurial) Side Hustles (OLD)

Honestly, not all blogs are evergreen. Some age like fine milk. This is one of the latter. Consider this a placeholder for a redux for technical reasons related to avoiding as many dead links as possible. I’ll update this same link when I have time, so you can still keep the page bookmarked. :)

What is a Film Market and how do they work?

You’ve probably heard of film festivals, but you might not have heard of Film Markets. In short, Film Festivals celebrate art, and film markets transact business. Read this for more.

After the prelude, you have a 50,000 foot view of AFM. Let’s zoom in a bit, and check out a bit more about the total landscape of Film Markets in general, as well as the sales cycle for them.

What’s the difference between a Film Market and a Film Festival?

When speaking, I get asked this question more than any other, with one possible exception that will be covered in the next chapter.

Put simply, a film festival is a celebration of the artistry of film. Film markets are centered around the commerce of film. Film festivals are about the pageantry of film, and film markets are about the business of it. Some festivals have a lot of crossover, like Sundance and Toronto. Some film festivals have markets attached. AFM is attached to the AFI Fest, Berlinale is attached to the European Film Market, and the Cannes Film Festival has the biggest film market in the world attached, Merche du Film.

The biggest difference between a film festival and a film market is the focus of the two. When most people thing of Cannes, they think of the festival, not the market. However anyone involved in distribution thinks the opposite. While the festival is full of red carpets and pageantry, the market side is much more about the business behind the scenes. More money flies around at Merche du Film than almost anywhere else in the word, at least in regards to the film industry.

Of course, I’m not trying to underplay the importance of film festivals. They serve a vital role in the promotion of the film. If used properly, they can greatly increase the visibility and marketability of the film, particularly if you’re self distributing. The bigger festivals will even help

21

Section 1: Pre-AFM

you get your film sold, or at least increase the sale price.

However, speaking solely in regards to international sales, the only festivals that really matter are top-tier festivals. These are festivals like Sundance, Tribeca, Toronto, and Cannes. Other festivals can help to raise your social media presence and marketing proliferation, but they won’t increase your international sales price in a meaningful way.

There’s already a book on film festivals. Chris Gores wrote it better than I could. You can find some helpful links to that in the resource packet at TheGuerrillaRep.com.

What are the other Film Markets?

While AFM is the biggest narrative feature film focused market in the US, there are many more media markets across the country and across the globe. Here are 14 Film and TV Markets you should know about, but there are many more. Markets generally take place for anywhere between a few days and a week around the same time every year. Here’s a guide table for reference. In the book, tbhis is a table, given my website builder won’t let be use a table, I’ll seperate them into bullets. The first will be a guide for the rest. Bold denotes major market.

Market Name

Location

When

Primarily for

American Film Market (AFM)

Santa Monica, CA

November

Narrative Features, especially genre pics

CineMart

Rotterdam, Netherlands

January

Co-Production

European Film Market (EFM)

Berlin, Germany

February

Narrative Features, esp genre pics, but more of a focus on dramas and festivals than the other major markets.

Hong Kong International Film and TV Market (FILMMART)

Hong Kong PRC

March

Narrative features, especially genre pictures, special focus on Asian content.

Hot Docs

Toronto, Canada

April/May

Documentary

Independent Film Week (Formerly IFP)

New York, New York, USA

September

Mixed, generally more drama than others

Marche du Film (Associated with Cannes IFF)

Nice, France

May

Narrative Features, especially Genre

MIPCOM

Nice, France

October

Television, Documentary

MIPTV

Nice, France

April

Television

National Media Market (NMM)

Charleston, South Carolina

November

NATPE (National Association of Television Program Executives)

Miami, FL, USA (Now Bahamas)

January

Television

TIFFCOM (Content Market at The Tokyo IFF)

Tokyo, Japan

October

Genre

Toronto International Film Fest

Toronto, Canada

September

Narrative, Esp. Thriller/Horror and Genre

How many Film Markets does a Sales Agent go to in a year?

Any good sales agent will go to at least the three major markets. Those would be AFM, EFM, and Marche du Film. If they’re not attending at least those three, it’s probably not a good idea to sign with them. Although, it’s better if they go to other markets as well since it often takes as many as 5 face to face touch points to get a sale.

As such, even if you can get your film placed at AFM, it may take a while to get your money back. Sometimes as much as a full market cycle.

Producer’s reps are a bit different. Producer’s reps take a bit less of a cut to sell domestically, and a much smaller cut to hand off to a sales agent. Since they maintain relationships primarily with Sales agents, they can get away with only attending one or two of those markets.

How many Film Markets should Filmmakers attend in a year?

Well, that’s a tricky question. There’s some very high-level networking to be had at such a convention, but beyond that there’s not always a great way to justify it as an ongoing expense.

I’d say a producer should attend several markets throughout the course of their career, just so they know what’s entailed in one. That said, they only consistently attend the closest one to them. If you’re looking to be a powerful executive producer or studio head, then you will need to spend time traveling to all of them, but if you just want to make movies, you’re probably alright only regularly attending one.

If you liked this, get the whole book on Amazon Below.

If you want more resources to help you at a film market, you should grab my FREE film business Resource Package. It’s got a (different) E-book, several templates to make your time at film markets more productive, as well as more time and money-saving resources!

Understanding Money

If you want to make movies, you need money. If you want to raise money, you mist first understand it.

Since my background is at the Institute for International Film Finance, and I put in a year at Global Film Ventures, I get a lot of filmmakers contacting me asking me to help them fund their films. Some of them are good pitches, but most are not. Getting investment for your film is incredibly difficult, if not nearly impossible. There are many reasons for this, but one that is not often talked about is the fact that many filmmakers have a mindset that money shouldn’t come with strings, and that all they should need to worry about is making the film.

There’s this attitude filmmakers have that someone should just give them a check and then go away so they can make the film. I’ve had many filmmakers say that flat out to me, and the ignorance of it is incredibly disturbing. There’s a lot more to investment than just writing checks.

Angel investors didn’t get their money by giving it to just anybody. Investors generally do quite a lot of legwork to research those with who they invest in, and they’ll never invest in someone they don’t trust. This attitude of “just give me the money and let me be” is a huge red flag, and makes an investor far less likely to trust you. If they don’t trust you, they won’t invest in you.

Once you take money from someone, you have a responsibility to them to send periodic updates and let them know how everything is progressing. You need to be available to take their calls at most any reasonable time and always return their correspondence within at most two business days. All money has strings, and you can’t expect an investor to just write you a check and then never check in on you.

Another attitude problem a lot of filmmakers have is that they feel they don’t need to understand business. Many feel just need to make the best film possible and money will come to them. While there’s a kernel of truth in that, relying solely on making the best film possible is a great way to end up broke with a film that never goes anywhere. The best product without a marketing team will never make money. Filmmakers

do need to make a great film, but they also need to understand at least the basics of how to promote a movie and how it will see revenue.

Distributing a film, promoting a film, and selling a film are all incredibly different skill sets that require decades to master. Filmmakers can’t be expected to be experts in every job involved in making a movie. They do, however, need to understand what they don’t know and compensate for that by getting people on their team that do understand how to do those jobs.

In essence, this is the difference between a producer and a production manager, or the difference between an executive producer and a line producer. Line producers and production managers are great at understanding how to manage a crew and get a film in the can. Producers need to have a good understanding of business, negotiation, deal-making, finance, and distribution. Executives do the latter almost to the exclusion of everything else. Every film needs at least one of each of these people, and really they shouldn’t be the same person filling multiple roles.

Every film needs people who understand money, how to raise it, how to make it back, and creative ways to save it. Filmmakers of all kinds can be excellent at the last part of that. Innovative bootstrapping is a skill perfected by many guerilla filmmakers. That said, you still need money, and people who understand how to make a film see revenue on your team.

Even if you find an intermediary who can help you get the money from angels, you’re still going to have to have regular phone calls and meetings with that intermediary. In fact, that intermediary is probably going to have more contact with you than an investor would because they understand both investment and filmmaking. You need people like this on your team, and you need to understand that you’re creating more than just a film. Every film is in essence a business, and in order to run a successful business you need skilled business people just as much as skilled artists and visionary directors.

Whenever you seek investment, it is into your business. You need to understand that the business side of the indusry is necessary. You also need to have an appreciation and at least a basic understanding of what it takes to make money in business. This should not be your sole consideration, but it does need to be part of your plan when creating a film. If you do not include this in your plan, you’ll never actually see revenue from your projects.

So readers, if you’ve ever thought that all you need is someone to write you a check; remove that notion from your head. In order to get money, you need to understand money. Only if you understand how money works, and have a good business plan will you be able to successfully get investment and make a profitable film.

the 5 Main Types of Indiefilm Distribution Media Rights - Redux

Indpendent films are sold based on 3 major criteria. Media Rights, Territory, and Language. Here’s an overview of the first.

Distribution deals tend to confuse and confound many filmmakers. While there are a lot of complicated places that revenue can get lost, the essence of distribution deals is quite simple. They’re essentially just parsing of different media rights to various territories around the world. However given the Black Box that is the world film distribution, it’s often unclear how these rights get structured. So with that, I thought it prudent to share some of the structure of these deals.

Generally, these rights are broken up both by territory and by media type. This post is by type, there will be a future post based on territory. Generally, you’ll need a very skilled Producer's Rep or a sales agent to sell these territories for you. Click here to find out the difference between those two.

Type 1: Theatrical

This should be fairly clear. Theatrical rights are for the rights to release in theaters. Again, this is usually done by territory. Producer’s Reps may help with this domestically, but you will generally need a sales agent to sell it internationally if you want a hope at getting any significant number of screens. You’ll also need a genre film to get a screen guarantee from a distributor.

There are a few other types of exhibition that would fall under this right umbrella. Education rights with classroom or school screenings are an example, as are community screenings that would take place at a venue other than a traditional theater. This right is generally quite easy to negotiate a distributor taking non-exclusive rights so you can exploit it yourself.

Type 2: Physical Media (I.E. Home Video/DVD/Blu-Ray)

Believe it or not, there is still a market for DVD and Blu-ray. A lot of it is international, but there are still major retailers like Wal-Mart, target, and occasionally Redbox. These are as they sound, and are most often sold to a sales agent who then sells them to wholesalers. There are also outlets that can help you self-distribute those rights, Allied Vaugn will even let you sell through major online storefronts including all the major places you can think of. These deals are normally done through a process known as Manufacture On Demand, or MOD. In general, if you can only find a title online, it’s probably fulfilled through a MOD process.

Type 3. Television Rights

In General, these rights are broken out into 3 sub categories, PayTV, CableTV, and FreeTV.

PayTV

Pay TV is essentially Premium TV. These are places like HBO, Starz, Showtime, etc. These deals are generally exclusive, and will often also include a Subscription Video On Demand (SVOD) license. This is so that the network can include the offering on their associated SVOD platforms and extensions through third-party services like Hulu or Amazon Prime.

For instance, this allows HBO to put the content on HBOMAX or Discovery+. There’s an ongoing shakeup in the SVOD space, but that’s better left for the SVOD section.

CableTV

Cable TV is as it would sound. It’s any channel accessible via terrestrial cable or satellite television. These providers have been largely consolidated and tend to pay significantly less than payTV outlets for independent films, although there are some notable exceptions to this rule. These outlets are less likely to take SVOD rights, but they’re not at all uncommon to be included in such a license.

More commonly, these outlets will take Free Ad-Supported Streaming Television Services (FAST) or Ad-supported Video on Demand (AVOD) rights. More on that in the VOD section.

In general, these networks survive on ad revenue and carriage fees. Ad revenue should be clear if you’re reading this, but carriage fees are a fee paid to each individual channel from every single cable subscription which includes that channel in its bundle.

Free/Network TV

As it would sound, Network or Free TV is for the major “Over the air” networks. In The US, These would be ABC, NBC, Fox, and CBS. Most of the time these channels will be accessible solely with an antenna. These are almost entirely supported by ad revenue, but they do get carriage fees from cable providers as well.

Type 4: VOD

VOD stands for Video On Demand. There’s more than one type of Video on Demand Service, and each type has different providers. Here’s a very brief outline of what the different types of VOD are, and some samples as to the people who provide that service.

-TVOD

This stands for Transactional VOD. This has largely replaced Pay Per View television rights and is generally the most accessible form of VOD. There are many platforms for PPVOD. The most obvious would be iTunes, Google Play, Amazon/Createspace, and Vimeo On Demand. Amazon is far and away the largest TVOD platform in terms of gross sales. Most films I worked on had between 60 and 80% of total TVOD sales come in through Amazon.

-SVOD

Subscription Video on Demand – [SVOD] is for VOD platforms that run on a subscription basis. This would be platforms like Netflix, and Hulu Plus, as well as extensions of PayTV and regular TV channels as mentioned above.

-AVOD/FAST

Ad supported Video on Demand (AVOD) are apps where you can watch content on demand for free with ads. Platforms for this are Tubi, Vudu Free, or even YouTube. (you should check me out there, ;) ). Free Ad Supported Streaming Television Services (FAST) aren’t technically VOD, as they’re not on demand. These platforms continually stream channels of content similar to cable television but deliver over the internet as opposed to being bound by terrestril cable or satelite. The most notable example of this is PlutoTV.

Type 5 - EST & Ancillary

EST refers to Electronic Sell Through. This is functionally what used to be known as Pay Per View, and is generally when you rent a movie through a cable or satellite box. Comcast InDemand and driectTV are good examples. Ancillary rights rever to any method of watching content outside of the standard methods listed above. Airlines and Cruise Ships are common examples. Airlines and cruise ships tend to exist outside of territorial rights though. Hotels, academic, or library rights may be considered ancillary right types as well.

Thank you so much for reading! In the process of porting my old website over to my new host, I realized this blog in particular needed A LOT of updating, so I hope you enjoyed it. If you did, please share it with your filmmaking community.

If you want more like this, you should consider signing up for my resource package. You’ll get monthly blog digests segmented by category and a heaping helping of templates, money-saving resources, and even an e-book! Join below.

If this is all a little intimidating and you feel like you need a guide to navigate distribiution, you should check out guerrilla rep medi services. If you want something even more in depth, we have books and courses you can check out, and if you just feel like more of this information should be be widely available, support me on substack or patreon. My main gig is actually financing and distributing films, so having a bit of money coming in helps keep me writing content just like this. Thanks so much!

The Importance of Specialization to Film Communities.

We all know that there are a lot of problems with most film schools. The foremost being that while they’re great at teaching you how to make a movie, they suck at teaching you how to make money doing it. There’s another one that isn’t generally talked about.

We all know that there are a lot of problems with most film schools. The foremost being that while they’re great at teaching you how to make a movie, they suck at teaching you how to make money doing it. While I’m personally working to fix that one, there’s another one that isn’t generally talked about.

Most film schools take a rather blanket approach to filmmaking. They teach everyone the skills of all positions on set, instead of focusing on being really good at one part of it. Because of this, many film schools are failing to prepare students for the real world they will compete in.

The attitude of being a jack of all trades often leads to being decent at everything, but excellent at nothing. Which is alright for someone who wants to make their own ultra low budget movies or make a few not great corporate clients. Unfortunately, we live and work in a highly specialized and extremely competitive industry. In order to find success, you must to be excellent at your craft. Unfortunately, Few Film Schools operate this way. Most teach you to be a jack of all trades, and it's just not possible for anyone to master all the skills necessary to do every job on set.

Not all of this is the fault of the schools. Most of them do offer specialization into Cinematography, Directing, Producing, Editing, Writing, and often even acting. However even with this specialization, many filmmakers are forced to perform most of the jobs on set, and get an attitude that they must do it all. Filmmaking is an incredibly collaborative medium, and it is an incredibly collaborative medium, and an attitude of one person being able to fill any and all jobs on set is counter-productive for the creation of high quality projects.

This is not the case for all film schools. The ones considered to be the best still prepare you to be excellent at one job. USC and UCLA foremost among them. However the same cannot be said for most film schools

Directing is always a difficult specialty. Nearly everyone wants to be a director. However if you want to be a director, then the best thing you can do is learn to direct actors. Directors need to have a vision, and they need to understand every part of the film, but the best directors are the ones who truly understand how to work with actors.

A director is responsible for nearly every creative element of the film, but much of it is delegated. Cinematographers handle the camera, Gaffers the lights, and editors the cuts. Performance is the only element left entirely to the director. It's important it be the director's primary focus, for better or worse, The performances will carry much of the project.

Cinematography is a skill that’s extremely transferrable, if you do it well. And a good cinematographer can always find work. But it is also good for a Cinematographer to know not just how to Light, but why to light. How can you paint a picture with shadow, and how can your dynamic range effect the feel of the shot. As a cinematographer, you must understand how to use every tool in your toolbelt.

A backing in photography is excellent for this, and can lead to a lot of work while you build your career and client base. Having your own gear and an understanding of how to create a stylized look can help you land a very good job with an ad agency or find your own clients while you network to get on projects you're more excited to be working on.

However, there's a lot of exciting things going on in the world of content marketing.

Writing is tough, the competition is high and everyone thinks they can do it. I've had bartenders and Lyft Drivers ask me to represent their scripts while in LA on business. As we all know, while anyone can write, few do it well. Even if you can write well, it is often difficult to break in. The most useful specialization for a screenwriter is learning to give coverage. It's hugely important and incredibly useful, and it also helps you develop relationships with producers. Another thing that writers, and everyone if I'm honest, is to write good copy. Spending a few hours learning the basics of copywriting will help you go so much farther in the world of independent film.

This whole Idea of specialization will help you to fit better into a larger film community. If you have something you can bring to the table for your community, it’s a lot more likely you’ll be able to find success. If we’re to really grow vibrant film communities outside of New York and LA, then the idea of specialization really needs to reach the local level that can compete with the production quality of the major hubs. That’s not possible without specialization.

There’s not much more specialized than being an executive producer. We focus solely on the business of entertainment and our skillsets are not always easy to find. If you’d like to know more, you should check out my free film business resource package for time and money-saving resources, templates, and even a free e-book! Join below.

If you want to stay specialized where you are, you might want to consider hiring a producer’s rep so you can focus on what you do best. If so, check out our services page. If you just like the content, and want to see more, check out my patreon and substack.

What does a Producer’s Rep Do Anyway?

Outside of the film industry, few people understand what a producer does. Inside of the indusrt, the jargon gets even deeper. This article examines the difference between Agents, Executive Producers, Producer’s of Marketing and Distribution, and Producer’s reps, as well as their roles and responsibilities.

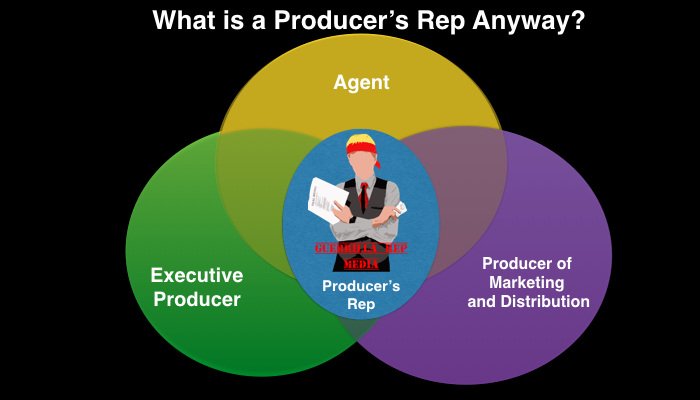

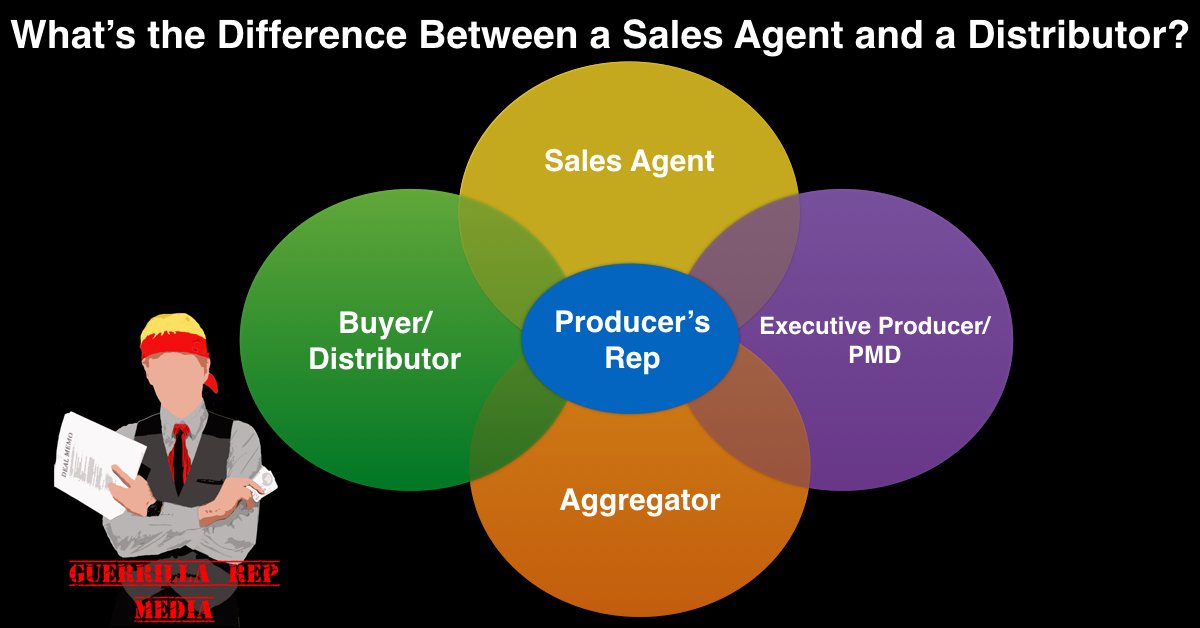

As stated in the article What's the difference between a sales agent and a distributor, one of the most common questions I get is What does a producer’s Rep Do? Since that post teaches the major distribution players are by type, (you should read it first.) I will now thoroughly answer what a producer’s rep does.

Simply put, a Producer’s rep is a mix between a PMD and an executive producer. A Producer’s Rep takes on a lot of the business development jobs for a film. We wear a lot of hats. Most often we'll connect filmmakers with completed projects to sales agents and negotiate the best possible deal. We're skilled negotiators with a deep knowledge of the film distribution scene, and entrenched connections there.

Would you rather watch or listed to a video instead of reading an article? Check out this video on my youtube channel for most of the same information.

If a producer's rep comes on in the beginning, we’ll do the job of an executive producer. We'll help you finance the film in the best way possible. not just through equity investment, but planning proper utilization of tax incentives, pre-sales, crowdfunding, occasional product placement, and sometimes helping to connect you to some of our angel contacts. That said, if we’ve never met, you have no track record and want us to start raising money for you, that probably won’t happen.

Not all producer’s reps will work with first-time directors and producers, I will, but generally only on completion or near the end of post-production. I will not help someone who I have not worked with before garner investment for their projects, except in very limited circumstances. I will help filmmakers get their financial mix in order. If a rep makes connections for investment, we need to know if the filmmakers I'm working with can deliver a quality product and get our investment contacts their money back.

A Good Producer’s Rep will also be able to act as a PMD, or at least refer you to a good one. We don't just work in traditional distribution, but we can help plan and implement other tactics including proper use of VOD. We’ll help you plan your marketing and distribution, then we’ll tell you how to implement it, helping you along the way. We’ll help you develop the best package in order to mitigate the risk taken by our investors. If we do bring on investors, you’d best believe we’re with you through the end of the project, to make sure that everyone ends up better off. We’ll check in and act as a coach to help you grow to the next level.

In a lot of ways, we’re agents for producers and films. Good reps, like good agents, won’t just think about this project, they’ll help you use your projects to move to the next step in your career.

So how do you pay a Producer’s Rep? Since the services we offer are so varied, our pay scale is as well. Some things are based primarily on commission. Sometimes that commission will come with a small[ish] non-refundable deposit that would be things like connecting to distribution. That commission is generally around 10%, but can range between 5-15%. Some things [like document and plan creation] are a flat fee, others are hourly plus commission on completion. That would apply primarily to packaging.

It is worth noting that not all producers reps are trustworthy. There are some that charge 5 figures upfront with no guarantee of performance. Admittedly, no one can guarantee they can sell your film, or get it financed investment. If they guarantee it and ask for a large upfront payment, you should be very wary of them. However, there are some with a strong track record of doing so. Just as you would when talking with sales agents, talk to people who have worked with them in the past.

Most reps will give you a discount based on doing multiple services. Remember to check last week's post for an idea of what each major player in indiefilm distribution Does!

If reading this made you think you want a producer’s rep, check out the Guerrilla Rep Media Services section!

If you like this content but aren’t ready to look into hiring us, but would like educational content you should for my Resources list to receive monthly blog digests segmented by topic. Additionally, you’ll get a FREE E-book of The Entrepreneurial Producer, plus a heaping helping of templates and money-saving resources to make your job finding money or the right distribution partner significantly easier.

What’s the Difference between a Sales Agent and Distributor?

Too few filmmakers understand distribution. Even something as basic as the disfference between each industry stakeholder is often lost in translation. This blog is a great place to start

As a Producer’s Rep, one of the questions I get asked the most is what exactly do I do? The term is somewhat ubiquitous and often mean different things to different people. So I thought it might be a good idea to settle the matter. In this post, I’ll outline what a producer’s rep is, and how we interact with sales agents, investors, filmmakers, and direct distribution channels. But first, we need a little background on some of the terms we’ll be using, and what they mean. These terms vary a bit depending on who you ask, but this is what I’ve been able to gather.

Would you rather watch/listen than read? Here’s a video on the same subject from my Youtube Channel.

Like and Subscribe! ;)

DISTRIBUTOR / BUYER

A distributor is someone who takes the product to an end user. This can be anything a buyer for a theater chain, a PayTV channel, a VOD platform, to an entertainment media buyer for a large retail chain like Wal-Mart, Target, or Best Buy. The rights Distributors take are generally broken up both by media type and by territory.

For Instance, if you were to sell a film to someone like Starz, they would likely take at least the US PayTV and SVOD rights, so that it could stream on premium television and their own app which appears on other SVOD services like Amazon Prime, or Hulu. They make take additional territories as well.

Conversely, it’s not uncommon to sell all of France or Germany in one go. It should are often sold by the language, so sometimes French Canada will sell with France. This is less common as of late.

Generally, these entities will pay real money via a wire transfer, and almost deal directly only with a sales agent. Although sometimes to a producer’s rep, and VOD platforms will generally deal with an aggregator. The traditional model of film finance is built around presales to these sorts of entities, but that presale model has recently shifted.

Recently, more sales agents have begun distributing in their territory of origin. XYZ is a good example of this. Some distributors have branched out into international sales. This is something that we did while I was at the Helm of Mutiny Pictures, to allow us to deal with filmmakers directly in a more comprehensive way.

Sales Agents

A Sales agent is a person or company with deep connections in the world of international sales. They specialize in segmenting and selling rights to individual territories. Often, they will be distributors themselves within their country of origin. This business is entirely relationship based, and the sales agents who have been around a while have very long-term business relationships with buyers all around the world. That’s why they travel to all of the major film markets.

Examples on the medium-large end would be Magnolia Pictures international, Tri-Coast Entertainment, and Multivissionaire. WonderPhil is up and coming as well, as is OneTwoThree Media. Lionsgate and Focus Features would also be considered distributors/sales agents, but they’re very hard to approach. They also both focus on Distribution over sales.

Generally, these sales specialists will work on commission. They may offer a minimum guarantee when you sign the film but that is not common unless you have names in your movie. Generally, they will charge recoupable expenses which mean you won’t see any money until after they’re recouped a certain amount. In general, these expenses will range between 10k and 30k, with the bulk falling between 20 and 25k. If it’s higher than 30k without a substantial screen guarantee, you should probably find another sales agent. There are ways around this, but I’ll have to touch on this in a later blog [or book].

A sales agent commission will be between 20% and 35%, this is variable depending on several factors, but generally 25% or under is generally good, and over 30% is a sign you should read more into this sales agent. Lately, this has been trending towards 20% with a slight uptick in expenses.

Aggregators

Aggregators are companies that help you get on VOD platforms. The most important service they provide is helping you conform to technical specifications required by various VOD platforms. This job is not as easy as you would think it is, which is why they charge so much. Additionally, they have better access to some VOD platforms than others. These days, it’s very difficult to get on iTunes or most platforms other than Amazon’s Transactional section without one.

Generally, aggregators charge a not insubstantial fee to get you on these platforms, and they offer little to help you market the project. Companies like this include Bitmax and arguably filmhub or IndieRights.

There are merits to going this this route, but they can be expensive, often costing about one thousand USD upfront and growing from there. If they operate on a commission like Filmhub or Indierights, they won’t help you with marketing so you’ll have to spend a decent amount there in order to get your film seen.

Producer of Marketing & Distribution (PMD)

In the words of Former ICM agent Jim Jeramanok, PMDs are worth their weight in gold. A PMD is a producer who helps you develop your marketing and social media strategy, your Festival strategy, and your distribution strategy. They’re also quite likely to have some connections in distribution. They’re there to give your film the best possible chance at making money when it’s done.

Generally, they’re paid just as any other producer would be, but if they’re good, they’re worth every penny. With a good PMD on board, your project’s chances for monetary success are exponentially better.

If you’re an investor reading this, you want any film you invest in to at least have access to a PMD or Producer’s Rep, if not a preferred sales agent or at least domestic distribution. (Not Financial Advice)

Executive Producer (EP)

In the independent film world, these are producers who are hyper-focused on the business of independent film. They either help raise money to make the film, or they help bring money back to those who put money into it in the first place. As such, the traditional definition in of an indiefilm executive producer is someone who helps you package projects by attaching, bankable talent, investors, or other forms of financing. They’ll also help you design a beneficial financial mix, [I.E. where can you best utilize tax incentives, presales, brand integration, and equity, and gap debt.] in order to help your project have the best chance of success. They can also play a significant role in distribution. The latter is where most of my EP credits come from.

Often, they’ll take a percentage of what they raise or what they bring in. sometimes they’ll require a retainer, but most of the time they should have some degree of deliverables such as business plans, decks, or similar as part of that. These fees should not be huge, but they will be enough to give you pause due to the amount of specialized work involved in doing these jobs.

Producer’s Reps

I’ll go into this much more deeply next week, But Producer’s Reps are essentially a connector between all of these sorts of people and companies. Producer’s Reps will connect you do sales agents, aggregators, buyers, and investors. But more than that, a good one will help you figure out how and when to contact each one. Most often, they’re credited as an executive producer or a consulting producer as the PGA does not have a separate title that applies to this particular skillset. For a more detailed analysis of what exactly a Producer's Rep does, Check out THIS BLOG!

Thank you so much for reading! If you found it useful, please share it to your social media or with your friends IRL. If you want more content like this in your inbox segmented by month, you should sign up for my resources pack. I send out blog digests covering the categories and tags on this site once per month. You’ll also get a free EBook of The entrepreneurial producer with this blog and 20 other articles in it, as well as templates, form letters, and money-saving resources for busy producers.

If this all seems like a lot, and you need your own personal docent to guide you through the process, check out the Guerrilla Rep Media Services page. If you’d rather just get a map or an audio tour and explore the industry on your own, the products page might have some useful books or courses for you. Finally, if you just appreciate the content and want to support it, check out my Patreon and substack.

Peruse the tags below for related free content!

7 Ways to become a leader in your Filmmaking (or Any) community

If you want to succeed in the film industry (or an industry for that matter) you’re going to have to grow a community around you and your work. Here’s how to rise to the top and lead a burgeoning community.

In any community, there are members who get more done than others. Some people rise to the top of the pile, while others tread water and don’t move their projects forward. Some people are only tolerated in their community, while others become leaders. It’s not random, the people who become community leaders do certain things to set themselves apart from the pack.

Successful entrepreneurs and filmmakers have a way of becoming leaders in their communities. The qualities required for both are remarkably similar. What are those qualities you ask? Fear, not my intrepid reader, what follows is a list of the 7 ways to become a leader in your filmmaking (or any) community.

1. Show up.

The old adage of half the battle is showing up is very true. If you always show up, then the community will begin to know you. After a while, you’ll become a face. You’ll get to know the other members of the community. If you’re always there then the organizers will eventually trust you with more responsibility. As you become more ingrained in the community, you will naturally figure out how the community functions. Once you know how the community functions, you can begin to become a leader within it.

2. Learn People’s Names

I’ll admit that I’m kind of bad at this one, but it really does make a difference. When you can greet a person by their name, then you’re going to forge a much better connection and business relationship with them. It can be hard to remember everyone’s names when you meet a lot of people at a networking event, but it really is worth the time and mental energy.

3. Actively participate

If you want to become a leader, you need to be noticed. It’s been said that only about 1 in 10 members of a community actively create content for it. If you sit in a corner and mess around on your phone, no one is going to notice you. If you ask intelligent questions, you become a part of the conversation. Take the time to actively participate, and you’ll be amazed at what it will do for your career.

4. Connect Both Online and Offline

If you only see members of your community once a month at whatever event you all frequent, your ties to them won’t be that strong. Assuming we’re talking about a professional community, connecting on LinkedIn will be the best place to do this. Google Plus and Twitter can also be good. Once you’ve known someone for a while, Facebook might not be a bad idea but you might want to add them to different lists in order to keep your personal and professional lives separate.

5. Don’t make it all about you.

The essence of community is being a part of something larger than yourself. Unfortunately, many people only take part in communities because they feel like they can get something out of it for their own personal projects. If you focus not only on your needs, but the needs of others, then you’re going to be able to get a lot farther in your community. Successful people never forget the ones who helped them get there. Not everyone you help will be successful, but if you help enough people then some of them will.

6. Help others before you ask for help.

If you have the resources and ability to help someone, you should. Time is one of those resources, so I’m not saying let your own projects or health fall by the wayside. However, helping people is key to building social capital.

7. Celebrate the successes of your community

If something good happens to someone in your community, celebrate it. Be happy for your community members who find success. Being envious of people for their achievements will prevent you from furthering your own goals. Negativity only creates more negativity. Luckily, the same can be said for positivity. If something big happens within the community, then share it. Revel in it. Take pride that you’re part of a community that is making things happen.

People remember how others respond to their success. Having found some level of success myself, I can tell you far too many respond with envy. They respond by tearing you down because they feel threatened by your success. Those people are toxic, and you need to associate yourself with people who will celebrate your successes. The only way to surround yourself with those types of people is to be one yourself.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

Thanks for reading! This blog is one of 21 articles included in The Entrepreneurial Producer. As part of the celebration of the relaunch of my website, I’m giving that Ebook away FOR FREE as part of my film business resource package. In addition to that FREE e-book, you’ll also get some other templates, form letters, as well as money and time-saving resources. You’ll even get monthly digests covering industry topics you’ll need to know to be a successful producer.

Check out the tags for more related content

One Simple Tool to Reopen Talks with Investors

Closing an investment is not the same thing as finding an investor. Here’s a very valuable tool for closing an investor you thought was lost.

Man in suit in front of a chalkboard with angel wings drawn on it holding fanned out 100 dollar bills in front of his face.

Taking a little bit of a break from the visions of the film industry and the direction that it should go in, this week I'll be offering a piece of useful advice for all the producers out there. I should start this by saying that I am NOT a financial planner. I am IN NO WAY qualified to evaluate security. I am also not qualified to give professional advice as to what stocks to buy, how to manage a portfolio, or anything even remotely related to that information.

In my time at the Institute for International Film Finance and Global Film Ventures, I’ve heard many people speak on various tricks to get Films Financed. One of the single most valuable tools in my arsenal is one that I will share with you now. I will say this was not developed by me, but rather by a speaker for one of my events a while back. I will start by saying that in order to be a producer, you need to understand your competition. Not just in terms of other movies and entertainment that are up against yours in the marketplace, but also how your investment stacks up against other potential investments that High Net Worth Individuals may be considering. This requires that a savvy producer understand the stock market, as it is the most common place where investors keep their money.

It’s important to understand that just because someone is worth 7 or 8 figures doesn’t mean they have millions of dollars to throw around. Most of their money is “Tied Up.” Pretty much any qualified Investor you’ll talk to will have a rather large stock portfolio. A lot of their stocks they’ll have been holding for quite a long time, and they’ll have grown quite a lot in value in the time they will have held them. Given the amount of Capitol Gains Tax they’d have to pay on selling those stocks, getting them the liquidity needed to invest in your film can be a difficult sell.

If you’re talking to a wealthy friend or relative, and they’re interested in your project, the little voice in their head is likely saying things along the lines of, “Hmm… I like it, it’s got potential, but I’d have to sell this, this and this, and my capital gains tax would be this…” That alone is often enough for them to not invest, sometimes simply out of the hassle and paperwork involved in the transaction, not to mention the loss of money. That, my dear readers, is where portfolio loans come in. A Portfolio Loan is essentially a mortgage on a stock portfolio. It allows the investor to keep the stocks in their portfolio, but also free up some money to invest in other projects, such as yours.

It’s extremely low interest, often below 4%. The interest varies week to week, so for precise rates have your Investor contact their broker and/or financial planner. It’s lower interest than borrowing on margin, and while there are many risks involved, the repayment terms are very flexible, and the interest can often be offset by stocks that pay dividends. Also, if you’re borrowing on Margin, you are technically only allowed to invest in other stocks, at least according to the SEC. Although that is admittedly not all that well enforced. This tool can be a great excuse to call up some of your potential investors who have all but turned you down, and can help to reopen conversations with them. It has done just that for me, as well as several of my clients.

In no waay should this be considered financial advice, but in my personal experience this tool is best used in times when the market is expected to go up over the period between when your investor funds your project and when you start to pay them back out. That makes it an excellent tool for when we’re heading towards the bottom of a bear market or towards the beginning of a bull market that is expected to continue. In times when the market is pretty much at its peak, it would probably make more sense to just liquidate part of their portfolio in favor of a higher-risk speculative investment such as an independent film.

Again, I’m not a financial planner, advisor, or a lawyer. Contact one of those people if you really want to know more about this, but just knowing what to ask about can be a huge leg up. As always, be well and thanks for reading, and please share this with your friends!

If you want to hear more from an experienced Executive Producer, or find other tips, tools, and templates you should sign up for my free film business resources package. It includes contact tracking templates, form letters, and even a deck template that should translate to your investors better than most look books sign up for that below and follow on social media for all the latest from Ben Yennie and Guerrilla Rep Media

If you liked this content, but need help from an experienced producer to take your project to the next level, check out the services offered by Guerrilla Rep Media by clicking the button below. If you’re the sort who would rather save some money and do it yourself but need a roadmap, check out my books, courses, and other standalone projects. Finally, if you just appreciate this content and want to support it, check out my Substack and Patreon. Those services don’t pay my bills the same way film projects do, but they help justify me creating more content like this.

Check out the tags below for more FREE content.

Why Film Needs Venture Capital

Part of creating a sustainable revolution in the film industry is creating a new system of finance. For that, we should look to other industries starting with Private Equity and Venture Capital. Here’s how we do that.

A lightbulb next to a chart outlining the allocation of venture funds in 2011 above a text blurb outlining the data source.

There’s an old joke that goes something like this. Three artists move to Los Angeles, a Fine Artist, a poet, and a Filmmaker. The first day they’re in town, they check out the Mann’s Chinese Theater. When they get there, a wave of inspiration overtakes them. The fine artist says, “This is incredible, I have to draw something! Does anyone have a piece of chalk?” Low and behold a random passerby happens to have one, and hands it over. The fine artist does a beautiful rendering on the sidewalk.

Watching this, the poet says, “I’ve had a flash of inspiration, I must write! Does anyone have a pen and paper?” It happens to be a friendly sort of Los Angeles day, and someone hands over a pen and paper. He writes a beautiful Shakespearean sonnet about his friend’s artistry with the chalk.

The filmmaker says “This is amazing, I’ve got to make a movie about it! Does anyone have any money?”

Even though the costs of making a film have been cut drastically, the joke remains true. I mentioned in my last post that the film world is in need of new money, and that what the film world really needs is something akin to Venture Capital. I think the topic deserves more exploration than a couple paragraphs in a post about transparency.

Venture capitalists bring far more than money to the table. They also bring connections and a vast knowledge of financial and industry specific business knowledge to the table. Essentially these people are experts at building companies, and when you really break it down the best films really are just companies creating a product.

The contribution of connections and knowledge is just as vital to the success of the startup as the money is. We have something somewhat similar in the film world, it’s generally the job of the executive producer to find the money for the film and put the right people in place to run the production and complete the product.

The biggest problem is that good executive producers with contact to money are few and far between, and there are very few connection points between the big money hubs and the independent film world. Filmmakers often don’t only need money, they need to have an understanding of distribution and finance that many simply do not have, and most film schools just do not teach. These positions are generally not full time positions, and most filmmakers just don’t have the money they need to pay people like this. If a venture capital model were to be adapted in film, the firm could link to these experts, and included in the budget for the film at a cost far less than it would normally be, because the person could split their time between all of the projects represented by the firm.

Most people understand that filmmakers need money, what many people do not understand is that there are very valid reasons for an investor to invest in film.A good investor knows that a diverse portfolio is far better than one that focuses solely on one industry. Industries can change and the revenue brought in by any single industry can crash with little notice. Savvy investors will seek to have money in many pots as it really helps to weather through downturns. Film is considered to be a mature industry, and has grown steadily over the past several years, even in the economic downturn. In fact, the film industry is moderately reversely dependent on the economy, so it often does better in economic downturns.

The biggest problem is that most investors just don’t invest in things they don’t know. Investors need to understand an investment before they put money into it.

Film is a highly specialized and inherently risky business. All the money goes away before any comes back, and that can scare off many investors. Especially since they often don’t understand what a good use of resources for a film is and are often incapable of seeing when the project should be stop-lossed as to not lose any more money.

One solution a venture capital firm could bring to this industry that single investors simply cannot is stage financing. Stage financing is a system of finance that is widely used in Silicon Valley. The concept is basically that the investors only release funds once certain checkpoints are met. Single angel investors do not have the time or expertise to act in this way, which is a big part of the reason for the standard escrow model. If a project that makes it through the screening process is only given the money they need for pre production up front, they must pass a review to have funds released for principle photography then it becomes a far more sustainable investment.

Filmmakers may balk at the idea of review, but quite frankly so long as the production is being well managed, they should be able to complete the checkpoints and have the additional funds released with little difficulty, assuming that the right review panel is put in place. The fund itself has every reason to see it’s projects through to completion, so it will only be filmmakers who are not doing their jobs that end up not passing the review process.

Edit: Additionally, there are deals that can be made to help agents and bankable talent feel more comfortable with such a process. This may be a subject of a later blog, and is mentioned in the comments.

Why does the fund have every reason to see films through to completion? Because if the films are not completed, then the fund will have lost all the money it put in with no chance of getting it back. That said, if the production is a disaster, and it’s clear that additional funds would not actually result in a finished and marketable film, then it is far better to cut losses and move on with other projects that have higher potential for revenue.

As mentioned in the last blog, a lack of transparent accounting is also a big issue with investors.

A single filmmaker does not really have the ability to negotiate with a distributor, at least not to a level necessary to resolve the transparency issue. In the relationship, the distributor has all of the power and there’s really very little most filmmakers, especially those just starting out, can do to change that.

But in film as in any industry, money talks. If there were a venture capital firm for film that only worked with distributors who have transparent books, and those distributors could then turn around and propose new projects to the venture capital firm, then some of the issues of transparent accounting could start to change. Many distributors, especially those working in the low budget sphere, are continually raising money for their own projects. So, having a good relationship with a venture capital firm is a big incentive to maintain good books and responsible business practices for filmmakers.

It got listed in the comments section of Black Box that filmmakers shouldn’t necessarily need to have that much business sense, since it takes their whole being to create. Filmmaking is indeed a collaborative effort, and it’s not a director’s job to think about target demographics and marketing strategies. The problem is the people in the film world that truly understand investment and recoupment are few and far between. Many of them also take advantage of filmmakers, as evidenced by the stories of studio accounting from Black Box. Part of what’s needed is the creation of teams that have what it takes to both tell quality stories with high production values, also get the films to market and figure out exit strategies, target demographics, and general budget recoupment tactics.