The Underlying Cause of Many Issues Facing The Indiefilm Industry.

There are many issues independent filmmakers complain about when it comes to the indie film business, many all stem from the film industry coping with he same problem, Uncertainty. This article expands on that to help creatives better adapt to it.

As an independent filmmaker, you probably didn’t get into the game to sell widgets or do insurance paperwork as your primary 9-5. As such, it’s completely understandable that indie film producers wouldn’t really consider the distributor’s perspective when making their independent films. Filmmakers got into the industry to make movies, which is an all-encompassing goal in and of itself.

Speaking from the other side of the negotiation table, there’s an issue that most independent filmmakers just don’t consider when they’re setting out to monetize their work. That issue is around the uncertainty of market demand that really only matters at least three years after you write your script, as well as the uncertainty that requires distributors and studios to plan for the inevitable unpredictability of that faces the film industry and likely always will.

This article is meant to outline some of the issues associated with uncertainty for those creatives so that they can better account for it down the line.

Content is King, but only if it’s good

For a long time, I thought that the saying content is king was primarily a platitude said by speakers at conventions to keep filmmakers making films. Obviously, distributors need films to sell in order to run their business. What most speakers leave unsaid is that there is such a gargantuan dirth of under-monetized independent film out there I thought it was something primarily meant to keep the film buyers in a superior position so they could get away with some of the shenanigans we all know independent film distributors and sales agents for. Having led a distribution company for a few years, I can say that both I and the speakers who say content is king on stage were wrong. Content is king, but only if good.

Well-made, engaging, commercial films will get distributors fighting for the right to distribute. Bad films will get bad deals which means the filmmaker is unlikely to ever see a cent. Unfortunately, the same is true for good films in a non-marketable genre, or with a hard-to-define audience.

Only about 1 in 10 films makes money

After having released many movies, I can tell you from experience that only about 1 in 10 films will make enough money to cover their budget over the course of a 7-year term distribution agreement. I know that’s a rough pill to swallow, but you should know it going in. About 20-30% of the others can make a meaningful portion of their budget back over the same time period if they’re working with an ethical sales agent or distribution company. The rest will get little to nothing back. Again, all of that is assuming you have a distributor or sales agent who actually pays you and is transparent in their bookkeeping, which is rare. This basic reality of the business influences many more choices made by your distributor than you may realize and greatly informs the business model and operations of distributors.

Nobody can pick winners all the time.

In the words of William Goldman, nobody knows anything. Having said that, I think Goldman’s statement is overly broad. I think there are so many factors that weigh on a single film’s success there’s absolutely no way that even the best distributor or analyst in the world could Plan for and create hit after hit. Pixar did in their early days, but they also had a functional monopoly of hot new technology and the finances and resources of Disney, so it’s not exactly a realistic use case for those of us operating on the independent side of the industry. In the world of distribution, if you get about half of the acquisitions you make to over-perform expectations you’ve done extremely well and you would be inducted into the hall of fame if we had one. On average, the best of us only get around 35%, but even if you get around 25% you’re still doing pretty alright and will likely keep your job.

This functionally means that even if your sales agent or distributor is being entirely genuine about their expectations for the film there’s at least a 50% chance they won’t be able to live up to their most optimistic projections. Again, I don’t mean this as a slight to those of us who work in acquisitions. There are so many variables that are impossible to predict. One example of such unpredictable complications (at least for the time) would be the initial release of The Boondock Saints hitting theaters the same week as the Columbine Shooting in Colorado. While mass shootings are sadly a near-daily occurrence in the US in 2023, Columbine was one of the first of its kind. Due to a fear of inadvertently endorsing vigilante justice, most theaters that were set to play the film dropped it. For a while this made The Boondock saints was one of the biggest box office bombs in movie history.

There’s no way a studio executive, writer, producer, or anyone involved in the release of this film could have predicted that, and as a direct result the film massively underperformed. Since it was a pretty modest budget for the time and the film found a second life as a cult classic it’s likely it remained as big a flop as it started.

Granted, this is an extreme example, but it is indicative of the butterfly effect that can cause even the best film with the best team to underperform.

Producers can’t always be relied on to help market their work.

Marketing a film is expensive and time-consuming. If you don’t have a big name to help you make a big splash, you’re going to need to help your distributor spread the word about your movie if you want it to find success. There are so many films released on a weekly basis that without the filmmakers helping to push the film to rise above the white noise caused by the glut of feature film releases the film doesn’t stand much of a chance of finding an audience. Unfortunately, not all producers can be relied upon to help market their own work.

Even at this late date, many producers feel that it should be entirely on the distributor to make their film a success. After all, isn’t that what their commission and their fees are for? While I can understand the sentiment and I even agree that most distributors should do more to earn their commissions it’s not as simple as it sounds. Independent Film Distributors have a lot more to do than it may initially appear. Delivery to each platform is extremely time-intensive, and we also need to handle a lot of regular pitches, shifting mandates, filmmaker relations, investor relations, buyer relations, press relations, and a whole lot more. If you work with us to make our job easier, you’ll get more meaningful attention paid to your film as we won’t have to spend time identifying and engaging with the core audience.

In the end, if you won’t promote your own work, how can you expect anyone else to? For more, read this blog.

RELATED: Why you NEED to help your distributor market your film (If they’ll let you)

A known cast helps everything, but the competition is fierce, and not everyone is honest.

In general, the best way to rise above the white noise created by the glut of independent films released on a regular basis is to attach a star to your film. I know, I know. Everyone says this, and it’s both hard and expensive. While it’s not as hard or expensive as you may think if you do it properly, it’s still outside the reach of most sub-100k feature filmmakers. If you do get a celebrity attached to your feature film, you’ll almost certainly get a lot of distributors coming to you in an attempt to procure the rights to your film.

Unfortunately, a mediocre genre film with a B list name in it is more likely to garner a decent return than a great film of the same genre without a name in it. Of course, exceptions exist but it is a key indicator that’s likely to lead to success.

The issue here is that while you may be able to get multiple distribution offers for your film, not all of them will be companies you want to work with. Most sales agents and distributors will do whatever they need to in order to get the film from you. After they get the film, whether they even live up to their own contract isn’t a guarantee. In most cases, it’s exceptionally difficult to get your rights back.

The outcome? Consolidation and risk aversion, Exploitation of Filmmakers, or sales agents make their own micro-budget content.

There have been massive industry-spanning consequences resulting from the high level of uncertainty coupled with dwindling revenue from physical media and transactional video-on-demand sales. Many of the resulting decisions that have led to extreme consolidation of the industry are made simply out of a need for the sales agent or distributor to make payroll, although often those issues extrapolate into something else. Additionally, almost all of them are bad for filmmakers.

The most obvious example of negative consequences for filmmakers is the fact that many contracts are structured in a way that exploits filmmakers by passing through disproportionate risk and falsified expenses. This is covered across the internet so I won’t go too far into it here. Additionally, in the last few years, the industry has been consolidating into the hands of fewer and fewer companies. This leads to less competition for acquisitions, which means lower payments, less transparency, and an explosion of growth in the exploitation mentioned above. Simply put, when there are fewer companies who can buy your film, they don’t have to do as much to get it.

Given all of this uncertainty, sales agents and distributors are less likely to acquire content outside of the standard genre fare they know they can sell. This means newer voices and content are likely to get lost in the shuffle. In order to combat this, some sales agents have started their own production lines to develop content that fits the needs of their buyers. The most notable recent example of this was Winnie The Pooh, Blood & Honey Which was made by ITN Studios. ITN was a distributor and sales agent for quite a while before Stuart decided the best move was to create a bespoke model for his buyers. It worked wonders and many sales agents are following their example.

The problem with the direct production model is primarily that it creates a new kind of competition for filmmakers, and could quite easily mean that the traditional method of acquisition for independent films is disrupted in a way that leaves independent artists completely out in the cold.

Again, all of these issues are greatly influenced if not caused by the issue of uncertainty of the independent film industry. Uncertainty faces every industry, but the level of it is significantly greater than in most other industries outside of early-stage high-growth startups or perhaps certain types of small businesses. However, there is one thing that is certain for filmmakers. If you sign up for my Newsletter you’ll get my independent film resource package which includes an independent film investment deck template, festival promotional brochure template, monthly content digests segmented by topic, a free e-book, white paper, and more! Click the button below to add it.

Thanks for reading, more next week, and please share this if you liked it!

Check out the tags below for related content!

What you CAN and CAN’T negotiate in an Indiefilm Distribution Deal

Negotiation is a skill, and it takes a while to understand it. Here are some things I’ve seen as an acquisitions agent for a US distributor, as well as from my time as a producer’s rep.

A HUGE part of my job as a producer’s rep has been to negotiate with sales agents and distributors on a filmmaker’s behalf. While I happen to think my contracts are exceptionally fair, most filmmakers tend to do some level of negotiation. However, others can overplay their hands and lose interest. I’ve checked up on some of the ones that did, and they didn’t make it anywhere. So, no matter who you intend to negotiate with here’s a list of what tends to be possible to negotiate.

One thing to keep in mind is your position as a filmmaker. Distributors tend to have more power in this negotiation. Filmmakers do still have power, as you own your film, but it’s important to keep in mind that in many circumstances, they’ll have significantly more options than you will.

It’s also important to note that these contracts are only as good as the people and companies you’re dealing with. So vetting them is important. The link below has more information on that.

Related: How to vet your sales agent distributor.

There are of course exceptions to these rules, but you knowing the general rules will help. Those exceptions are directly tied to the quality and marketability of your film.

What you CAN negotiate

These are things you CAN negotiate, within reason.

Exclusions

Distribution deals are all about rights transfers and sales. In general, you can negotiate a few exclusions to keep back and sell yourself. It’s important to note that you shouldn’t try for too many of these though, as the distributor needs to be able to recoup what they put into your film. Here are some of the common ones

Crowdfunding fulfillment

Website sales

Tertiary regions the film was shot in.

In general, all rights are given exclusively, but crowdfunding fulfillment might need to be carved out so you can fulfill your obligations to your backers. I’ve never had trouble with this one.

Generally, it’s wise to retain the right to sell your film transactionally through your own website using a platform like Vimeo OnDemand or Vimeo OTT. Distributors tend not to utilize these platforms, so they generally won’t have an issue with it so long as they get advisement on release timing AND it’s only available on said platform transactionally. That is to say, people must pay to purchase or rent the film.

If the film was shot in a very minor territory like the Caribbean, Paraguay, parts of Africa, or maybe parts of the Philippines, it might be possible for you to retain those territories and sell the film yourself. Be careful with how many of those you do.

Marketing Oversight (Home Territory)

Pretty much no matter what territory you’re from, you have some pretty meaningful ability to negotiate additional marketing oversight. This is not an unlimited right, however, and it’s common that final say will remain with the sales agent or distributor. It’s important to do your diligence on how they’ve used that oversight in the past.

Term (To an extent)

If a Distributor or sales agent brings you an agreement with a 25-year term and no MG, walk away. If a Distributor tries to get a 12-15 year term, try to get them down to 10. That’s the industry standard for what we work on.

Exit Conditions (to Some Extent)

You need to make sure that you have aa route out if things go sideways. In general, you need a bankruptcy exit, and I would push for an option to exit on acquisition of the distributor, or if a key person leaves.

What you CAN’T GENERALLY negotiate

(but should probably look out for)

Here’s what you generally can’t negotiate. There are exceptions to how much you can negotiate this, but no matter what these are things you need to fully understand.

The Payment Waterfall

I wrote about the waterfall fairly extensively in the related blog linked below. The biggest issue is that most distributors start taking their commissions BEFORE they recoup their expenses. I understand how and why they do it, but it’s generally not the best.

The biggest negotiation you MIGHT be able to get is what’s known as a producer’s corridor, which effectively helps you get a small amount of money from the first sale. Generally you’ll be placed (essentially) in line with the distributor or sales agent, which means it will take significantly longer for them to recoup their expenses. That said, any way you slice those numbers, you still get paid more.

Related: Indiefilm Distribution Payment Waterfalls 101

Related: The Problem with the Film Distribution Payments

Recoupable Expenses

Recoupable expenses are money a distributor or sales agent invest into the marketing of your film. They generally have to get this back before paying you. The exception above is notable. Generally, there is little ability to negotiate this but you should make sure you get the right to audit at least once per year.

Related: What is a Recoupable Expense in Indiefilm Distribution

Payment Schedule

The payment schedule is how often you receive Both a report and a check. In general, they start out quarterly and move to semi-annually over 2 years. There are exceptions, some of my buyers report monthly. However, in general, after 2 years most of the revenue has been made, and the reports will continue to get smaller and smaller.

DON’T EVEN BRING THESE ONES UP

These are issues you just can’t bring up. The distributor might walk away if you do.

Their Commission

Don’t bring up the sales agent’s commission. You probably don’t have the negotiating power to alter it beyond the corridor I mentioned above.

EXCLUSIVITY

I wrote a whole blog about this linked below, but the basics of it are that we’re essentially dealing with the rights to infinitely replicate media broken up by territory and media right type. The addition of exclusivity is the only way to limit the supply, which is the only reason the rights to the content have any value at all.

DIRECT ACCESS TO THEIR CONTACTS.

These contacts are generally very expensive to acquire, and the entire business model of the sales agent or distributor relies on maintaining good relationships with them. No distributor is ever going to give this to you. They’ll get very annoyed about you even asking.

Thanks so much for reading! If you think that this all sounds like a bit much, and would rather have help negotiating, check out Guerrilla Rep Media’s services which include producer’s representation. your film using the button below. If you need more convincing, join my email list for free educational and news digests and resources on the entertainment business which include an investment deck template, a contact tracking template to help you keep track of the distributors you’re talking to, and a whole lot more.

CHECK THE TAGS BELOW FOR MORE CONTENT

Filmmakers Glossary of Film Investment Terminology

It’s hard to raise funding for a film, and the contracts get confusing quickly. Here’s a glossary to help you understand the mountain of paperwork you’ll need to sign to get your film financed. This blog doesn’t mean you don’t still need a lawyer (I’m not one, and this isn’t legal advice), but it will help you understand the paperwork you’re sent.

Last week I laid out a glossary of general-use film business terms, but the blog ended up a bit too long and dense to be a single post. So, I broke it into two. Last week was the basics of business terms, this week is the next level, and focuses entirely on investment terms. Some of these may seem tangential and unnecessary, however if your goal is to close an investor, you’ll need to thoroughly speak their language. If there’s something you don’t see here, check out last week’s blog here. I’m not a lawyer, this isn’t legal advice, and you should have a solid attorney on your team before trying to close an investment round. With that out of the way, let’s get started.

Capital

While many types exist, The term most commonly refers to money.

Liquid Capital

Money that can be spent immediately, or near immediately. Non-liquid capital would be considered something like real estate holdings which would first need to be liquidated in order to sell.

Principle

In finance: it’s general the initial capital investment or the remaining balance on a debt.

Interest

A percentage fee is added on to the principle of a loan or line of credit.

Compound interest

Interest on the principle of the loan and interest.

Simply: interest on interest.

High-Risk Investment

An investment where an investor may lose most or all of the money they put in. Independent Films are always high-risk investments

Securities and Exchanges Commission (SEC)

The main financial regulatory agency in the United States. It oversees most forms of investment.

Accredited Investor

A person of means who is generally considered to have enough business know-how to appraise an investment, pay someone to appraise it for them, or who wouldn’t be completely destitute from taking a high risk-gamble. As of the date of this publishing, according to the SEC the investor must meet either (NOT both of) the income or net worth requirement in order to be considered an accredited investor.

Income Requirements

1.If filing individually, a person must have made 200,000 USD a year for the past 2 years, and be likely to do the same this year.

2.If filing Jointly, a household must have made 300,000 USD a year for the past 2 years, and be likely to do the same this year.

Net Worth.

The investor or household must have 1 million dollars in net worth OUTSIDE of their primary residence.

High Net Worth Individual (HNWI)

Outside the obvious, this term is generally a financial industry term for accredited investor

Edgar Database

A database of high-risk investments maintained by the SEC that is only accessible to Accredited investors and licensed brokerage or investment firms.

Financing Round

A round of financing or funding that is large enough to take an organization or project to the next major milestone. For how this works in film, check out the youtube video I’ve linked below, and the blog linked below that.

Related Video: The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Financing

Related Blog: The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Financing

Business Plan

A document written by an entrepreneur or filmmaker outlining their investment. In the film industry, this document will also often educate the investor on how the industry functions as a whole. This document is also known as a prospectus, but that term is not as commonly used as it once was.

Private Placement Memorandum (PPM)

A document that’s filed with the SEC for investors to consider investing in your project. Frequently an attorney will base this document off of the filmmaker or entrepreneur’s business plan. In most cases, a PPM will be registered with the aforementioned Edgar database for a modest filing fee.

Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Financial documents consisting of an expected income breakdown, cash-flow statement, and top sheet budget to be invaded in the business plan and function as the basis for many of the financial sections of other documents

The Three points above are heavily outlined in my business planning blog series.

Related: How to write an independent Film Business Plan (1/7)

Backed Debt

A secured loan backed by something like a tax incentive or pre-sale agreement.

Unbacked Debt

An unsecured loan, or debt without backing. Generally very high interest.

Financial Gap

The space between what you are able to raise and the amount you need to finish your project.

Financial Markets

A market where stocks, bonds, derivatives, or other securities are bought and sold. Common examples in the US would be the DOW and the NASDAQ.

Film Market

A convention where films are bought and sold primarily by sales agents and distributors. For more, check out the link below.

Related: What is a film market and how does it work?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The total value of all newly finished goods in a given country during a set timespan. Most commonly calculated on an annual basis.

Recession

A macroeconomic term signifying a period of a significant decline in economic activity. It’s generally only recognized after two consecutive quarters of down financial markets.

Depression

A severe recession that lasts longer than 3 years and corresponds with a drop in GDP of at least 10%

Bull Market

A market that’s strong and growing. It’s called a bull market as the upward trending graph looks like a bull nodding its head according to some people on Wall Street.

Bear Market

Yes, I spelled that right. It’s a financial market that’s going down, or staying stagnant. The name comes from a bear swiping its claws down. Probably the same wall street guy came up with it.

Thanks so much for reading! If you liked this, please make sure to check out last week’s general financing glossary, as well as my glossary of distribution terms. Also, please share. It helps A LOT.

Filmmakers Glossary of Business Terms

Additionally, make sure you grab my free Film Business Resource Package to get a print ready PDF version of all 3 glossaries.

Check the tags below for more related content.

How Independent Filmmakers can THRIVE in the current distribution Marketplace.

If you want to make a career in film, you need to make money. To do that effectively, you need distribution, and that sphere is a tumultuous mess. Here’s a guide to thriving in the current distribution landscape

To cap off my first-ever distribution month, I thought I’d talk a little bit about where Independent Film Distribution is heading. Markets are going to be a big center of commerce for the film industry for a few years, but they’re going to continue to wane for the truly independent filmmakers, which means one of the biggest areas for entry for filmmakers is likely to go away. With the fall of Distribber, and how Amazon looks like it’s going to scale back its filmmaker direct distribution programs there’s only one real path left for filmmakers. That path is to build an audience that’s highly engaged with your content and distribute not only your film to them but other products related to your Intellectual property (IP.)

BUILD AN ENGAGED AUDIENCE

The first step in this (as I’ve brought up in at least half of the blogs this month…) is to build a highly engaged audience and following. This is something that Youtubers have become fantastic about. You have to have lots of touch points with your audience and provide them a perspective that they emote with but can’t find anywhere else. By that I mean…

Create Niche Content that speaks to an underserved audience

With a massive glut of generalized content, You have to identify an underserved niche and start to make authentic, high-quality content that speaks specifically to a small niche of people. This turns the old TV model on its head, instead of being a 6/10 for 10 people, you need to be a 10/10 for 2 people, and budget your film in such a way that you can keep your business afloat on the revenue from that much smaller audience. Luckily, when you do this you’ll be able to successfully sell the film, as you won’t be competing as directly with outlets with huge, bland libraries.

Think less about the format

Movies don’t just have to be 90-minute feature films any more. If you can establish a following, keep content coming in the form of shorts, webseries, and features. Don’t spend more time on them than you have to, but make sure that you continue to release new content to engage with your audience.

Sell Merchandise

Once you have a dedicated following, think about ancillary ways you can monetize your brand and your content. Bands sell T-Shirts at their shows as their primary source of revenue, and film trends tend to follow about 5-10 years behind the music industry. You have to start building ways to monetize your Intellectual Property and your Brand beyond simply selling your movie at 3.99 a pop.

Community Screenings

Theatrical releases are not cost-effective for many filmmakers. Instead, you can focus on building community screenings that give your core audience a place to congregate, and if you organize them well they can also be a great place to sell merch. It’s also a great place for you as the filmmaker to Skype in and answer questions directly.

Create Custom Experiences around your IP

Mark Cuban (former owner of Landmark Theaters and Shark on Shark Tank) is fairly well known for saying this is the future of entertainment. It’s not always easy for Indies to commute in this space, but if you’re releasing a horror film you might consider a themed haunted house as part of a release or as part of a community screening. There are other ways to make this work in conjunction with your core IP, but it’s difficult to scale and tends to be a custom solution for each film.

Thanks so much for reading! This blog is something of a mix between a distribution blog and something to make you think a little bit more like an entrepreneur. If you like this sort of content, make sure you come back in February for Entrepreneurship Month. If you don’t want to miss it, make sure you subscribe to my mailing list or check out my Youtube Channel. If you want to be extra awesome, throw me a few bucks on Patreon. Links below.

Check out the tags below for related content.

22 Indiefilm Distribution Definitions Filmmakers NEED to know

There are a lot of terms of art in film distribution. Here’s a primer.

If you’re going to read and understand your distribution agreement, then there’s some terminology you have to grasp first. So with that in mind, here’s a breakdown of some key terminology you ABSOLUTELY need to know if you’re going to get traditional distribution for your film.

This is one of those blogs I should probably start out by saying that I’m not a lawyer. Always talk to a lawyer when looking at a film or media distribution contract. With that out of the way, I’d recommend we get started.

1. License

At its core, a license for an independent film or media project is the right to exploit the content for financial gain. Every other piece of a license agreement is clarifying the limitations of that license.

2. Licensor

A licensor is a person or entity that is licensing a piece of media to another entity to either distribute or sub-distribute its content. In general, this is the filmmaker when the filmmaker is dealing with a sales agent or producer’s rep, or the sales agent or producer’s rep when they’re dealing with distributors.

3. Licensee

The License is the entity that is acquiring the content to distribute it and exploit it for financial gain. In the instance of filmmakers and sales agents, it would be the sales agent, in the instance of sales agents and distributors, it would be the distributor.

4. Producer’s Representative (Producer’s Rep)

An agent who acts on behalf of a filmmaker or film to get the best possible sales and distribution deals.

Related: What does a Producer’s Rep Actually do, anyway?

5. Sales Agent

A Company that licenses films from sales agents or Producer’s Reps in order to sub-license the film to territorial distributors around the world.

6. Distributor

A company that directly exploits a film in a given territory on agreed upon media right types.

Related: What’s the difference between a sales agent and distributor

7. MG (Minimum Guarantee)

This is a huge one. It’s the amount of money you get up front from a sales agent, or a sales agent receives from a distributor. The biggest difference between this and a license fee is that at least in theory an MG has the potential to receive more in residual payments beyond the additional payment. In practice, this is less common.

8. License Fee

A license fee is a set amount of money paid by a distributor to exploit media in a defined territory and set of media rights. Unlike a minimum guarantee, a License fee is the total amount of payment the licensor will receive over the course of the license, regardless of the financial success the film goes on to achieve. License fees can be paid in one lump sum, or over the course of the license.

9. Revenue Share

Revenue share is the other most common way films can receive payment. Revenue share essentially means that the licensee will split the revenue with the licensor according to an agreed-upon commission generally after they recoup their expenses.

10. Producer’s Corridor

A producer’s corridor is an alternate payment waterfall of money a filmmaker is paid prior to the licensee recouping their expenses. This generally means that the producer is paid from dollar one.

11. Term

Term is the length of time a contract is in place. For most independent film sales agency contracts, the term is generally 5-7 years.

12. Region

The instances that generally apply to traditional distribution in the modern-day region refer to a set of territories in which a film can be distributed in. While they vary slightly from sales agency to sales agency, they are generally English Speaking, Europe, Latin America, Asia/Far East, and others.

13. Territory

When it comes to film distribution and international sales. territories are areas within a region that add greater specificity to where a sales agent can parse rights. Latin America is both a region and a territory.

14. Media Rights

The sorts of media that a distributor has to exploit in a given territory or set of territories.

Related: Indiefilm Media Right types

15. Benelux

A territory consisting of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

16. Four-Wall

The act of renting theaters in order to screen your film in them. It generally involves a not insignificant upfront fee, and as a result, all money returns to the licensor.

17. Community Screening

An alternative to a theatrical run for films with a strong niche or cause. See below for more information.

Related: How Community Screenings can replace a Theatrical Run

Related: 9 Essential Elements of Independent Film Community Screening Package

18. Payment Waterfall

When it comes to independent film distribution agreements, a payment waterfall is contractual representation How many flows from stakeholder to stakeholder? If there is a producer’s corridor or some other non-standard modifications of a license agreement, there may be more than one waterfall in said contract.

Related: IndieFilm Distribution Payment Waterfalls 101

19. Collection Account

A collection account is an account that a sales agent pays into which pays out all other stakeholders according to a pre-defined set of parameters.

20. Reports

In the context of independent film distribution and international sales agreements, a report is a statement made monthly, quarterly, bi-annually, or annually that states all incomes and expenses for a film. Generally, this is accompanied by a check one is due.

21. Payment Threshold

When it comes to film and media distribution, a payment threshold is a minimum payment owed by a licensee in order to issue a payment to a licensee. This payment amount is generally dependent on what payment method is being utilized. For instance, the minimum is for a wire transfer is generally higher than a check which in turn is generally higher than for a direct deposit.

22. Recoupable Expense

A recoupable expense is an investment made into marketing or distribution-related expenses by a licensee. This investment will need to be paid back before the licensee pays the licensor, with the notable exception of the producer’s corridor. Generally, these investments will fall into one of 3 categories of capped, uncapped, and uncovered expenses. For more information, please check out the blog below.

Related: What are recoupable expenses?

BONUS! - Expense Cap

An expense cap is a cap on the total amount of expenses that a licensee is able to take out before paying the licensor. There are exceptions, see the related link above for more information.

Thank you so much for reading the glossary! I hope it’s Helpful. If this is all intimidating and you need a little help, consider hiring a professional to assist you in the process. So you could consider checking out Guerrilla Rep Media’s services. These blogs Blogs are largely a public service and marketing tool for me, most of my business is from representing and consulting with filmmakers just like you. You can learn more and submit your film via the link below. Or, if you're not ready for that, but want to support more content like this, join my email list to stay up to date on new offerings and get an awesome film business resource package while you’re there.

Check the tags below for related content

Can You Get Your Movie on Netflix or Disney+ By Yourself?

Every filmmaker wants to get their movie on the major streamers. Few know how. This might help.

At least until recently, a lot of filmmakers assumed that they could get on any platform they needed to be on just by calling up Distribber or another aggregator like Quiver. With the fallout of the fall of Distribber, many filmmakers are wondering what they can do for distribution. So, I thought I’d share some knowledge as to what platforms a filmmaker can still get on themselves using aggregators like Quiver, and what platforms you’ll need an accomplished sales distributor, or producer’s rep to get on.

I’m going to break this into general media right types. If you’re not sure what that means, learn more by clicking through to the related blog below.

Related: Independent Film Media Right types.

Also, this analysis is based on the US Market

Theatrical

Most distributors just won’t do this for most films, however, the ones that can do it tend to either rent the theaters outright or be extremely skilled salespeople with deep connections to the booking agents for theaters who will book the films on a revenue share basis. It's just too much work for buyers to work directly with Filmmakers in this fashion.

For filmmakers, the most economical solutions tend to be either paying to rent a theater for a few screens or using a service like Tugg, to have a screening demanded if the film has enough of a following to make it work. I have my issues with their model, but that’s a topic for a future blog/video.

Physical Media:

Distributors have a lot more options for physical media than filmmakers tend to. Some distributors still replicate DVDs on a massive scale, which gives them the ability to get higher quality disks and get them into brick-and-mortar stores like Walmart, Target, Family Video, or kiosks like Redbox. Many distribution companies also have access to libraries. Also, Blu-Ray in general is only really available on a wide scale through a distributor.

Even if they use a Manufacture on Demand (MOD) service, they tend to have access to companies who will put them out on the online storefronts of pretty much anywhere that sells DVDs and Blu-Rays. This is largely due to the fact that those companies tend to only publish catalogs.

If you’re a filmmaker, you’ll generally be limited to either buying a few thousand DVDs with no guaranteed warehouse solution or distribution network, or you’ll be limited to using something similar to Createspace to put them up on Amazon. While this tends to have the highest margins, it doesn’t tend to move a lot of products, and the quality of the product is generally pretty low.

Broadcast, PayTV, and Ancillary (Generally Airline)

To get on any network or PayTv channel, you’ll need the help of a distribution company. Same for airlines. These entire right types are not generally available to you as a filmmaker.

Video On Demand (VOD)

For ease, I’m going to break this into a few categories that are generally accepted within the industry. Those categories are Transactional VOD (TVOD) Subscription VOD (SVOD) and (AVOD)

Transactional Video On Demand (TVOD)

In General, TVOD is pretty accessible to filmmakers on their own. Filmmakers can pay an aggregator to get you on most platforms for a fee. These platforms include iTunes, Google Play/YouTube, Fandango Now, and many others. Also, Filmmakers have been able to put their own work up on Amazon Instant video largely for free until recently, although it seems those winds may be changing. Either way, filmmakers can use Vimeo OTT or Vimeo On Demand to sell the film directly through their website.

There are, however, more than a Few TVOD platforms that only a distributor can access. These include a subset of TVOD called Electronic Sell Through VOD (ESTVOD) that’s primarily used for paid on-demand offerings of cable and satellite providers, as well as the occasional hotel chain. The hotel chains VOD offerings have greatly declined in recent years as free WiFi has become commonplace. Additionally, there’s a service that enables your content to be rented through library systems that are only accessible to distributors with decently sized catalogs.

Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD)

In order to get on any platform like Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, HBO NOW, HBO MAX, or any other major streaming platform, you need the help of a distributor. Distribber SAID they could pitch you, but that turned out to not be as true as you might hope, and their pitch fee was the size of most commissions a sales agent would take. Also, their success rate was abysmal for someone charging up front. This was primarily due to them pitching dozens of films a month, and as such them not getting much attention.

If you want to utilize your SVOD rights as a filmmaker, you pretty much have three options. Put it on Amazon Prime, (at least for now.) You can start your own subscription service using Vimeo OTT, or try to sell it to people who started their own subscription services that you’ve found. I doubt those last people will have much money though.

Advertising Supported Video On Demand (AVOD)

Finally, we come to Advertising Supported Video on Demand or AVOD. This is an exciting space that’s only recently emerged. The two biggest players that do it profitably are TubiTV and PlutoTV. Both of which only deal with filmmakers and sales agents with large catalogs of high-quality, distributable films. This means they generally only deal with distributors or sales agents.

If you’re a filmmaker, you can put your movie on YouTube in the normal way for AVOD dollars, but it’s generally inadvisable for feature film content. It’s good for vlogs about film distribution though..,

Thanks so much for reading!

Educational content isn’t my primary business, the reason I know this stuff is I work in the field. If you’d like to work with me, submit your project idea via the link below. Distribution and brokerage tasks are on commission, earlier stage projects involve some reasonable fees. Also, If you like content like this, you should join my mailing list. It will get you lots of great blog digests of content just like this, as well as notices of major releases from Guerrilla Rep Media.

Check the tags below for related content!

What does current state of Independent Film Distribution look like in 2020?

If you want to make movies, they have to make money. Here’s a throwback guide.

2019 was quite a year for most of us, and while we’re entering 2020 with more stable economic footing than we expected, there are definitely some notable industry trends heating up that I thought to weigh in on a bit and let those of you who frequent my tiny corner of the internet know my thoughts on the matter.

Note from the future: Oof. That stable economic footing did not last.

The SVOD Wars

Anyone who’s been on the internet, watched TV, or stepped out of their house in the last 10 months has probably seen at least about 50 ads for Disney+. It’s the latest major entry into the Subscription Video on Demand market (SVOD) and it really changed the power dynamics of that particular section of the industry. Disney is moving a lot of their legacy content onto the platform as with the fall of DVD the vault isn’t as profitable as it once was. Now that Disney is here, it’s going to shape up the landscape a significant amount. For more on that, check back in a few weeks for a post elaborating on the state of SVOD and how it changes the whole landscape.

The fallout from the Distribber Debacle

If you follow Alex Ferrari of Indie Film Hustle as I do, you’ll be well aware of the issues facing Distribber and GoDigital. Through reports from the people they took money and films from, it seems clear that they’ve proven themselves to be every bit as untrustworthy as the sales agents and distributors we’ve all heard about. So the big question here is if aggregators don’t deliver or screw you, where else can a filmmaker go to get their film out there? Should they use the old path, and go to a film market?

Film Markets

I’ve said it before, and I maintain that I would not have a career had I not gone to the American Film Market. However, if I were to give advice to anyone starting out today, I don’t know if I’d tell them they should go. While there were a lot of buyers at AFM last year, none of them seemed to be buying enough to sustain that sort of system. According to the Hollywood reporter, this year AFM hit “Schlock bottom” and the rich got richer.

It’s not the right political climate for that to continue, and most of the people reading this probably aren’t studio heads or those making 5-10mm dollar features.

For more on Markets, Check out my book!

AVOD Surges

I think it’s very likely that we’ll see a massive surge in the Advertising supported video on demand market over the course of 2020. That market is poised to explode, especially in the even of an economic downturn. People are aware of AVOD, but many don’t really watch much of it due to a lack of content. That’s changing. Quickly. TubiTV and PlutoTV’s buyers were some of the only people acquiring catalogs en mass at AFM in November. Their user base is global, and growing.

If there is an economic downturn, it’s likely that more people will have less money and more time. That spells a boom for free entertainment, and the longer people watch the more ad impressions the platform racks up, even if the Cost per impression goes down due to lack of purchase power of the viewer. If your content is up there, the more you engage with a new user base and the greater the royalties.

So how do you maximize your profit in this landscape?

BUILD YOUR AUDIENCE!

Everything mentioned above are tactics to make your content available to your audience. They all share the same problem, the inability to generate an audience or help a new audience discover your work. So if you do one thing to build your filmmaking career, it should be to grow your audience. If you have an engaged audience, it can sustain your career more than anything else. It can make it more likely you’ll get picked up by an SVOD platform, it can help you have leverage with aggregators and sales agents you meet at markets, and if you are looking to grow your audience by having a free AVOD platform they can watch your content through that’s much more selective than something like YouTube can help you to do so.

So if you want to grow your profits from film distribution, the solution is simple. Build an audience hungry for your content. If you want some help with that, the button below will let you join my email list and get a marketing packet that will help you with some additional information, money saving links, and templates.

Check the tags below for related content

5 Things to expect from the 2019 American Film Market #AFM2019

Film markets were changing even before COVID. Here’s an analysis from 2019.

AFM this year will be interesting. Here’s the current state from someone who’s been going for 10 years, and has been a Practicing Producer’s rep for 6 years. Two quick things before we get started.

First, You should definitely go to AFM at least once. It’s eye-opening, and if I hadn’t done it I probably wouldn’t have a career.

Second: These opinions are mine alone, and have not been approved, endorsed, or otherwise condoned by the International Film and Television Alliance (IFTA) owner of the American Film Market. (AFM is also a Registered Trademark of the IFTA.)

And with that, we’re on to the less optimistic (or legal) parts of the current state of AFM and Film Markets.

Film Markets could be in trouble.

All Film markets might be in trouble. I’ve spoken with many buyers, and they’re pretty much ready to pack up shop. There’s nowhere near as much money in it as there used to be, and it’s difficult to contuse to turn a profit in this changing landscape. They’re not going away in the next year or so, but they are likely to recede over time.

AFM is Becoming much more filmmaker focused in their marketing, which means less involvement from Buyers and Sales agents.

AFM Themselves have been shifting focus to their filmmaker services and somewhat away from their buyer and exhibitor services.

That's not necessarily a bad thing in general. It's what I tend to do with content like this, but I go for a very different customer set than AFM has historically.

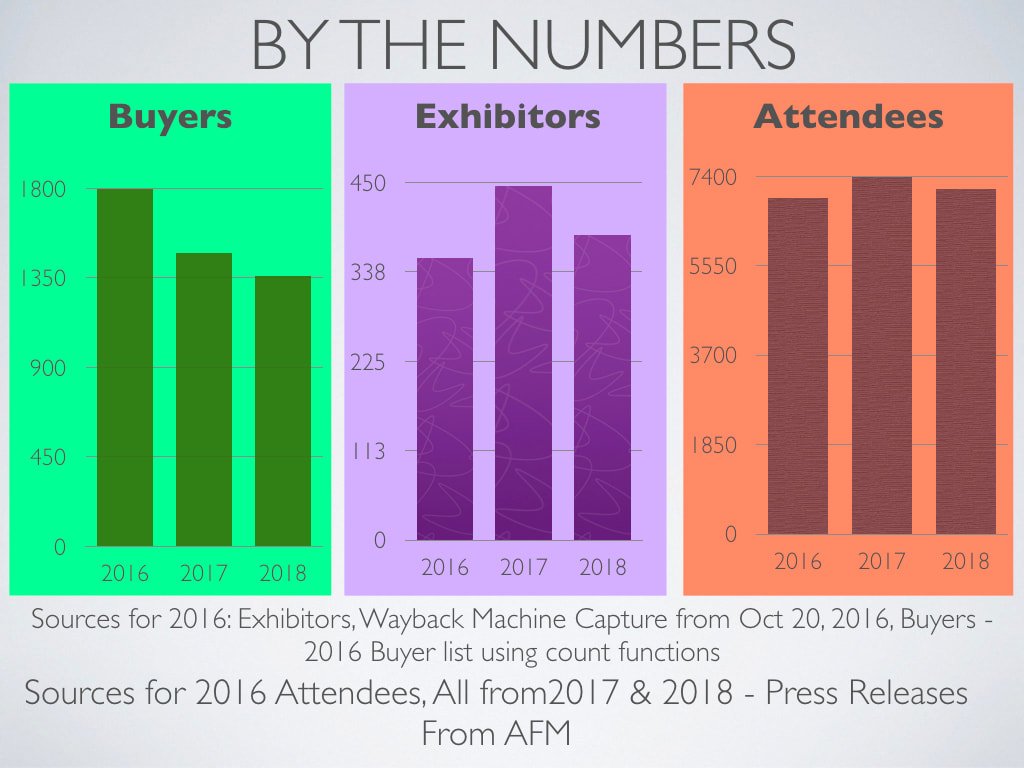

Buyer numbers have been on the decline for a few years, and if they continue to decline it will be difficult to attract the higher-priced exhibitors, and the culture of AFM and all markets is likely to change. The Image below should help illustrate my point.

The current system is prone to collapse in a down economy

2008 was Terrible for AFM. I’ve been expecting a recession to happen at any point since around this time last year. While the time that I was expecting it to happen seems to have passed, I’m still convinced of an impending recession, but willing to admit I might have missed the timing and the immediacy.

In any case, when the recession happened in 2008, the market dried up and it still hasn’t fully recovered. If we were to see another recession, it might spell the nail in the coffin for AFM and potentially the entire market scene. What would replace it has yet to be seen, as after Distribber’s recent collapse it will be very interesting to see how filmmakers can get their films out there.

Buyers have been on the decline for a few years.

I mentioned this above, but total buyer attendance have been on the decline for the past 2 years. It’s difficult to tell whether the size and number of deals have been increased, but given that the number of tickets sold on the top 100 box office films have remained largely stationary despite the box office revenue going up as well as a few other metrics and the general sentiment of my contacts on the sales agency side I’d be inclined to doubt it.

Again, if buyers dry up, sales agents won’t keep coming. When I’ve talked to sales agents about this over drinks, there’s a feeling of extreme pessimism bordering on depression about the current state.

AVOD and SVOD buyers likely to be the biggest players this year.

Given that many believe there’s a looking recession, SVOD and AVOD players are going to be even more sought after than they already are. AVOD is free for all, and SVOD doesn’t require extra payment on the consumer end. Given that the economy is a house of cards, many people who are struggling financially are more likely to cut services and stop buying individual rentals. They might even cancel subscriptions, which is likely to lead to a greater viewership of TubiTv, PlutoTV and other similar services.

Thanks so much for reading. If you want more on AFM, Check out Last Week’s blog, my first appearance on IndieFilm Hustle, or my book. Also, if this all seems a little dauting, consider submitting your film via the link below.

6 Things for Filmmakers to Prepare for the 2019 American Film Market #AFM2019

If you want to get the most out of the American Film Marktet, you need to prepare. Here’s what you need.

With AFM 2019 right around the corner, it’s time for filmmakers to prepare for the market and do their best to get a traditional distribution deal. For those of you who don’t know, AFM is still the best place for American Filmmakers to get traditional, non-DIY distribution. So, with that in mind, here are the major things you need to prepare.

Also, For legal reasons, I need to say that the following: The American Film Market® AFM® are registered trademarks of the International Film and Television Alliance® (IFTA®) Any and all Opinions expressed in this video are Not Endorsed by the International Film and Television Alliance® or leadership at the American Film Market.

Just in case you'd rather watch than listen, Here's a Youtube Video on this topic!

Leads Lists

You need to know what sales agents and distributors you want to submit your film to. This starts with research and leads lists. You need to figure out which sales agents tend to work in your genre and budget level, what similar films they’ve helped sell recently, what their current market lineup is, whether they require recognizable names, and who the name of their acquisitions lead and CEO are.

To make your job easier, I put a free template in my resources packet which you can get by signing up below.

Join my mailing list and get the FREE AFM Advance contact tracking template.

Trailers

You need to get their attention, and a trailer is a great way to do it. I’ve gotten limited theatrical agreements based on an excellent trailer. See that trailer here.

If you don’t have a trailer, you can submit without it. However, it will be much less likely to achieve the desired results.

Pitches

There are elements of an indie film pitch. I tackle the topic in extreme detail in my book, but here’s an overview of what needs to go into that 10-30 second pitch.

Title of Film

Stage of development

Any attachments

Genre

Sub-Genre/Audience

Budget Range

Check out my book on Amazon for the full chapter

Related: What investors need to know about your movie

Key Art

You’ll need a poster, even if it’s a temp poster that’s eye catching and will convince the sales agent they can move units. It can be a temp poster, but it needs to invoke the spirit of the film and imbue a sense of intrigue for anyone who looks at it.

Promotional materials

Once you’ve got the key art, you can use it to create promotional materials. One of those would be a quarter page flyer, another may be a tri-fold brochure. I’ve included a pages and word document for use at festivals in the resources packet, but it could be modified for AFM. If I get a few people tweeting at me or commenting the want it on my youtube videos that they’d like that, I might make it.

Screening links

If your film is done, you need screeners. The distributors will need to see it, and they’ll probably want a Vimeo screener. Youtube unlisted or private won’t due, as the compression on Youtube makes it difficult to see all the technical issues with the film.

If you can get it out in advance of the market, all the better. It normally takes a few markets to start seeing money from your film if you don’t get a minimum guarantee. Getting that started would be in the best interest of all involved.

Thanks so much for reading. If you liked this and want more, come back next week for what you should expect from AFM 2019, as well as where the market seems to be heading. OR, if you can’t wait, you could listen to me on Indie Film Hustle Talking about AFM.

You could also check out my book!

It’s the first book on Film Markets, used as a supplemental text in at least 10 film schools, and is still the highest selling book on film markets. Check it out on Amazon Prime, Kindle, Audiobook on Audible, Online at Barnes and Nobles, Your Local Library, and anywhere books are sold. Also, join my email list to get a great indiefilm resource package totally free!

Check the tags below for related content

The 6 Steps to Negotiating an Indiefilm Distribution Deal

If you want the best distribution deal for your independent film, you have to negotiate. Here’s a guide to get you started.

Much of my job as a producer’s rep is negotiating deals on behalf of filmmakers. However, now that I’m doing more direct distribution, I’m realizing there are several things about this process that most filmmakers don’t understand. As I tend to write a blog whenever I run into a question enough that I feel my time is better spent writing my full answer instead of explaining it again, here’s a top-level guide on the process of negotiating an independent film distribution deal.

Submission

Generally, the first stage of the independent distribution process is submitting the film to the distributor. There are a few ways this can happen. Some distributors have forms on their website (mine is here) Others will reach out to films their interested in directly. Some will have emails you can send your submissions to. There are a few things to keep in mind here, but in the interest of brevity, just check out the blog I’ve linked to below. There’s a lot of useful information in that blog, but I will say that YES, THE DISTRIBUTOR NEEDS A SCREENER IF THEY’RE ASKING FOR ONE.

Related: What you NEED to know BEFORE submitting to film distributors

Initial Talk

Generally, the next step is for the distributor to watch the film. I have a 20-minute rule, and that’s pretty common. Generally, if I make it through the entire film, I’ll make an offer. If I don’t, I won’t ever make an offer. If I’m requesting a call, I’m normally doing so to size up the filmmaker and see if they’re going to be a problem to work with.

This is not an uncommon move for distributors that actually talk to filmmakers and sales agents. Generally, we want to discuss the film as well as size up the filmmaker before we send them a template contract.

Template Contract

Generally, when we send over the template contract, it will be watermarked and a PDF so that the filmmaker can understand our general terms. This also won’t have any identifying information for the film on there. We’ll also attach it. Few appendices to the contract can change more quickly than the contract itself. My deliverables contract is pretty comprehensive as of right now, but honestly, I think I’ll pare it down soon as I haven’t had to use much of what’s in there yet.

Red-Lining

The next major step in the process of the distribution deal is going through and inserting modifications and comments using the relevant function on your preferred word processor. Most of the time they’ll send it in MSWord, but you can open Word with pretty much any word processor and this is unlikely to be too affected by the formatting changes that happen as a result of putting the document into pages or open office. That said, version errors around tracking changes do happen, and if you find yourself in that situation comment on everything.

What you should go through and do is make sure track changes are turned on, and then comment on anything you have a question about and cross out anything that simply won’t work for you.

NOTE FROM THE FUTURE: Since someone commented on this at a workshop, I’m aware that Redlining has another historical context in the US, but it is the common parlance for this form of contract markup as well. I’m in favor of negotiating distribution deals, and not in favor of racist housing policies.

Counter-Offers

Generally, distributors and sales agents will review your changes, accept the ones they can, reject the ones they can’t, and offer compromises on others. While there are some exceptions to this framework, after the first round of negotiations, it’s often a take-it-or-leave-it arrangement. If it’s good enough, sign it and you’re in business. If not, walk away.

Quality control

Most sales agents and distributors will have you send the film to a lab to make sure the film passes stringent technical standards. If you have technically adept editor friends, you’ll want them to do a pass first, as each time you go through QC it will cost you between 800 & 1500 bucks. You will need to use their lab, but it’s best for everyone if it passes the first time.

If you need help negotiating with sales agents or just need distribution in general, that’s what I do for a living. Check out my services using the button below. If you want more content like this, sign up for my email list so you can get content digests by topic in your inbox once a month, plus some great film business and film marketing resources including templates, ebooks, and money-saving resources.

Check the tags below for related content

How To Title a Film so it SELLS

One of the most important parts of selling your film is the title. Here’s a guide to titling your independent film so it stands out to viewers, sales agents, and distributors.

They say don’t judge a book by its cover, so you’d think it should follow that you shouldn’t judge a film by its title. You would think wrong. Title is a hugely important part of your film marketing, and it should be something you think about from the very beginning, not simply as an afterthought. So here’s how to go about creating a title that will stick.

Short

Brevity is key when it comes to titles. You don’t want more than one or two words. If it starts with A or a number, that can be better as some cataloging systems in various parts of the world still primarily use Alphatical Sorting. This is less important than it used to be, as most of the major players have algorithms that take a lot more into account when recommending a film. Altough if you look at films from the early 2010s, you’ll notice a disproportionate amount that start with a number, A, or B. This is why.

The reason you want it to be short is that shot can be easier to remember, and easier to make an impact with. This leads me to the next point.

Accurate to the film

The title of the film definitely needs to reflect the film itself, otherwise it’s not going to ring true to anyone who watches the film, which will end poorly for you. More in the blog below

Related: The SINGLE most important thing in your Movie Marketing

Punchy

Being punchy is about being memorable. Think about the difference between A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones. Game of Thrones the same general intellectual property, fewer words, much more punchy and much more memorable. Although A Song of Ice and Fire is also a thematically relevant title, Game of Thrones is much easier to latch on to.

It’s got to be Memorable

There’s a strong chance that if you and your distributor are doing your marketing and publicity right, a potential customer will have heard of your film prior to whenever they come across the ability to watch the film. Here are some Examples

Zombie with a Shotgun

Snakes on a Plane

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

These are all genre examples I could think of off the top of my head, but there are lots of other things that make your title memorable. Comment some of your favorites and I might include them in the YouTube Port.

If the title is memorable, they’re more likely to move to the next step in the independent film purchase process. More below.

Related: The independent film purchase process

Unique (or at least highly unusual) for SEO.

Rising above the vast amount of noise due to the glut of content created in the indiefilm world is crucial to success. Good SEO is key to that. If people hear about your movie, you don’t want it to be hard to find. As such, you should be thinking about how to best differentiate yourself from the slew of content out there, and choosing an unusual title is part of that.

It doesn’t need to be unique, we’re not talking about exclusivity and trademarks here. It does, however need to be more discoverable than a film with a title like Peter Pan that’s made multiple times every single year.

When we released The Devil’s restaurant, it was as a result of a change from “The Restaurant” primarily for SEO and memorability purposes.

Easy to spell

If people keep misspelling your title, it will make it harder to index and harder to find. I’ll admit I’m a hypocrite on this one. “Guerrilla” is extremely hard to spell. That said, I made the mistake so you don’t have to, and you might see some more corrections I’m making on that soon.

Be Careful of Double-Entendres

Titles with double meanings can be great, but if it’s not something you intended it can be extremely bad. Examples off the top of my head could be Snatch, Fire Down Below, or Free Willy. Great titles, terrible for immature jerks who blog.

Expect the title to change for the international releases

A lot of movie marketing tends to change depending on what country the film is being released in. This is especially true for the title. One film I represented came to me as Paralyitic, then was distributed internationally as Still Alive, and marketed domestically as Narco Hitman. Another was Luna De Cigarres in South America, Cicada Moon in the US (Originally), and Filthy Luck internationally.

Also, yes. Your distributor has the right to change the title. The best way to avoid them doing it is to give them no reason to.

If you like this blog, you’d probably like others I write, so sign up for my email list via the button below. Also, check me out on YouTube for more film-related content you can listen to instead of reading.

Check the tags below for more related content.

What is a Recoupable Expense in Independent Film Distribution?

Distribution is expensive, here’s how distributors classify their expenses.

Filmmakers Ask me about Recoupable Expenses all the time. A lot of filmmakers think that recoupable expenses mean money they have to pay. Except in some VERY limited circumstances, that’s not the case.

A recoupable expense is simply an expense that a distributor or sales agent fronts to your film. Another way of looking at this is that your distributor is your last investor, as they’re putting in a zero-interest loan in the form of paying for fees and services necessary to take the film to market. Most of the time, the distributor will need to get that money back before they start paying the filmmaker. Distributors and sales agents have businesses to run and generally put money into anywhere between 24 and 60 films every year. Without the ability to recoup what we put in, distributors would not be able to continue to invest in new films.

Before we really get into what each type of recoupable expense is. There are generally 2 or 3 types. Capped, uncapped, and Uncovered Expenses. Here’s what they mean.

Capped Expenses

These are expenses that fall into a cap that cannot be exceeded by the distributor. It’s normally a total cap that encompasses all expenses listed in an appendix. If the expense is listed as capped, it is generally a total cap, not an individual cap. A lot of filmmakers ask for individual caps but most distributors won’t do that. We did at Mutiny for the sake of transparency, but probably caused more problems than it solved due to confusion around the expense system.

Generally, there’s a reserve for capped expenses that often just ends up being the total amount of the expense cap. This should be too bad as most of the capped expenses will be spent getting the film ready to take to market.

Examples of Capped Expenses

This is not meant to be a complete list, but it is some of the most common examples. (I did take these from my Appendix B, but I added a few.)

Key Art Generation

DVD Art Generation

DVD Menu Generation

Trailer Generation

Aggregation fees

M.O.D. Listing Fees

ISBN listing fees

Publicity fees (generally Cross Collateralized with other clients at the same stage.)

Social Media Advertising

Market Fees.

Minimum Guarantee (If Any)

These are all parts of bringing a film to market that are largely unavoidable. Personally, I don’t spend the money if I don’t need to. Like, if the film has a phenomenal trailer and key art, I don’t make new key art or cut a new trailer. As a result, I don’t charge for those expenses. This decision is solely at the discretion of the distributor, generally speaking. Also, this is very much the rarity.

Market fees will often be on the recoupable expenses (They’re not on mine, but that’s another story.) However, if they are there they should definitely be cross collateralized. No single film should bear the total cost of market fees for a slate.

Uncapped Expenses

Uncapped expenses are exactly what they sound like they are. That said, they’re not necessarily as scary as they sound like they are, providing that you’re not dealing with a predatory sales agent or distributor. Expenses a distributor covers but are not subject to caps. These expenses are generally things that you’d often want to go higher, as it means more sales are being made. Look at the examples below.

Examples of Uncapped Expenses.

Again, this is not a complete list.

Physical Media Replication.

DCP Generation.

Errors and Omissions Insurance (as needed)

Any expense outlined in As Needed deliverables.

4-Walled Theaters (Upon Mutual Agreement in Writing)

In order to replicate more DVDs & Blu-Rays, a distributor must be selling them. You want them to do that. In order to generate more DCPs the Distributor must be booking theaters, which is generally a good thing. Errors and Omissions insurance is generally only required for large PayTV or SVOD deals (like Netflix, Hulu, Starz, Showtime, and HBO) or broadcast deals. As such, if you need E&O you probably got a big SVOD or Broadcast deal.

Related: Indiefilm Media Right Types

Regarding needed Deliverables, there are some deliverables that a re only needed in very limited circumstances like Beta Tapes, and others. There are reasons for each of them, but they get added beyond the cap as they’re difficult to anticipate. Here’s the relevant section of a series I wrote on distribution deliverables.

Related: Distribution Deliverables 4/4 - As Needed Deliverables.

Uncovered Expenses

Uncovered expenses is generally anything not listed in the appendix, although some expenses may not be covered like the 4-Walled Theaters listed above. These are expenses that the filmmaker may be invoiced for. They are rare, and the filmmaker SHOULD have advance notice of them.

Some exceptions

For a long time I thought the term “Recoupable expense” was self-explanatory, but given all the questions I’ve gotten about it, I thought I would make sure it was said completely plain. As stated right at the top, most of the time, the filmmaker is not liable for unrecouped expenses. There are two primary exceptions. The first is the uncovered expenses above, where filmmakers will be invoiced immediately. This is rare, and generally VERY transparent. If it’s not, that’s another issue.

The other exception is generally if the filmmaker tries to take the film back prior to the close of the full term of the contract while expenses remain to be recouped. That's also normally spelled out in a contract.

Thanks for Reading! As you can see, writing blogs and creating content is not my only (or even my primary job.) I also represent movies for sales and distribution. If you’d like me to consider yours, use the services button below. If you want to continue to reap the benefits of this free knowledge, grab my free indiefilm business resource package! some free resources, join my mailing list. You’ll get free blog digests that are like a topical e-book in your inbox every month, as well as templates to help you prep for festivals and investors or track your contact with sales agents, an actual e-book, and a whitepaper. That one is the lowest button

Check the tags below for more related content.

One HUGE Don't When Dealing with Film Distributors

There are many things you SHOULD do when selling your film with your distributor. There’s one BIG thing you should NEVER do.

As with nearly anything in life, there are dos and don’ts when you; ’re dealing with your independent film distributor. Also as with most things in life, there is (at least) one thing you can do that will irreparably harm your relationship with that distributor and might even result in legal action taken against you. What is it? Read on to find out.

DON’T GO AROUND YOUR DISTRIBUTOR OR SALES AGENT TO SELL YOUR FILM

Once you sign with a producer’s rep, sales agent, or Distributor for your project, they have the right to negotiate on your behalf. Many buyers won’t deal with filmmakers directly, so the point of contact will either be your producer’s rep or Sales agent.

While most buyers will appreciate the filmmakers helping to push the film, they will not be so grateful for reaching out to the buyer directly about reports, or any other form of unapproved contact.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t help promote your film in ways that it makes sense to do so. See the blogs below for reasons why.

Related: WHY you should help your distributor MARKET your MOVIE

Related: HOW to Best COLLABORATE your Distributor MARKET your Movie

The biggest takeaway for how to market your movie that you can take from the blog above is to only post approved links. If you’re smart, you’ll also include Vimeo on Demand and Vimeo OTT as a holdback for you to sell the film through your own website. Distributors tend not to utilize that right, so it’s generally something that you’ll be able to negotiate. It’s included as a holdback in my standard template contracts for the filmmaker’s country of origin. I do stipulate that it’s generally subject to advisement regarding the timing of the release.

Another thing that you should be fine “selling” is whatever you need to fulfill any crowdfunding obligations like DVDs, Blu-Rays, and TVOD Screeners. Although again, you should make sure to negotiate this into your distribution agreement. That said, it’s never been an issue, although it might be subject to the same sort of advisement on timing as the Vimeo on Demand example above.

If you distributor does not agree to either of the stipulations above, you should consider walking. Here are some tips on vetting your distributor/Sales agent, and producer’s rep.

Related: How to vet your distributor/Sales Agent

Related: How to Vet Your Producer’s Rep

The biggest thing you need to keep in mind is that no matter how much you disagree with the choices on artwork and marketing made by the distributor, you should not post any unauthorized sales links. If you do, you could be putting yourself in a pretty massive legal liability.

This one came out a little short, but thanks for reading anyway. If you like it and want to see more content like this, you should join my mailing list. You’ll get monthly blog digests segmented by topic, it’s like a short e-book in your inbox every month FOR FREE! You’ll also get access to my resources packet, which includes an actual e-book, whitepaper, several templates, and more!

Finally, if you’ve got a project you’d like a guiding hand through this process, I offer individual consultation, as well as consideration for my distribution, marketing, business planning, and financial services packets, use the submit your film button. Thanks, and see you next week.

How best to COLLABORATE with your Distributor to Market your Movie

Good relationships are about give and take. Here’s a basic ruleset for working with your distributor or sales agent.

The Distributor’s job is largely to make your film available for sale and set it up in such a way that people are likely to buy it. Some will work to market your film, but most won’t. Even when they do market your film, you helping market your work will make the marketing your distributor does much more effective. However, there are some basic rules that you should follow to make sure everything goes as well.

Quick disclaimer: This assumes that they'll work with you on it. that's not always a safe assumption, although it should be something you talk about when you're in negotiations with your sales agent and distributor.

1. COMMUNICATE with your distributor.

If you want your relationship with your distributor to be effective, then you need to lay out what you would define as success. You should listen to when they need something from you, and work towards making it happen as quickly as possible. Do what you can to help them promote your film.

A lot of the communication with your distributor will likely be at the beginning of your relationship in closing the contract. You can learn a lot about them through this process, but the most important thing to do before you sign is call 3 of their previous clients. Here’s a link for more information about doing your due diligence.

Related: 5 Rules for vetting your Distributor/Sales Agent

Also, you might want to understand what a film distribution contract looks like to better facilitate that communication. The blog below may help.

Related: The 7 Main Indiefilm Distribution Deal points

2. Make sure you ONLY sell the OFFICIAL links

Unless you redline the ability to sell your film through Vimeo through your own website, you should ONLY post the official sales links for your film that your distributor will set up. Even if you have the right to sell the film through your own website, you should still at least occasionally post the distributor’s sales links. Not only does it help keep your distributor happy, it also makes your film look bigger since its available in more places.

3. Take as many interviews as you can, and seek them out where appropriate.

If you want to build a career in film, you will need to build a brand for yourself as a filmmaker. A brand will help you engage with your community, find work, get more sales for the work you produce yourself, and can even help you finance your next project. Getting Press will help you expand that brand. It also helps raise awareness of your film, which in turn will help move more units or get more views and can create a positive feedback loop to help you build your career. In essence, it’s the very definition of a win-win.

4. Keep your social media up to date!