Filmmakers Glossary of Film Investment Terminology

It’s hard to raise funding for a film, and the contracts get confusing quickly. Here’s a glossary to help you understand the mountain of paperwork you’ll need to sign to get your film financed. This blog doesn’t mean you don’t still need a lawyer (I’m not one, and this isn’t legal advice), but it will help you understand the paperwork you’re sent.

Last week I laid out a glossary of general-use film business terms, but the blog ended up a bit too long and dense to be a single post. So, I broke it into two. Last week was the basics of business terms, this week is the next level, and focuses entirely on investment terms. Some of these may seem tangential and unnecessary, however if your goal is to close an investor, you’ll need to thoroughly speak their language. If there’s something you don’t see here, check out last week’s blog here. I’m not a lawyer, this isn’t legal advice, and you should have a solid attorney on your team before trying to close an investment round. With that out of the way, let’s get started.

Capital

While many types exist, The term most commonly refers to money.

Liquid Capital

Money that can be spent immediately, or near immediately. Non-liquid capital would be considered something like real estate holdings which would first need to be liquidated in order to sell.

Principle

In finance: it’s general the initial capital investment or the remaining balance on a debt.

Interest

A percentage fee is added on to the principle of a loan or line of credit.

Compound interest

Interest on the principle of the loan and interest.

Simply: interest on interest.

High-Risk Investment

An investment where an investor may lose most or all of the money they put in. Independent Films are always high-risk investments

Securities and Exchanges Commission (SEC)

The main financial regulatory agency in the United States. It oversees most forms of investment.

Accredited Investor

A person of means who is generally considered to have enough business know-how to appraise an investment, pay someone to appraise it for them, or who wouldn’t be completely destitute from taking a high risk-gamble. As of the date of this publishing, according to the SEC the investor must meet either (NOT both of) the income or net worth requirement in order to be considered an accredited investor.

Income Requirements

1.If filing individually, a person must have made 200,000 USD a year for the past 2 years, and be likely to do the same this year.

2.If filing Jointly, a household must have made 300,000 USD a year for the past 2 years, and be likely to do the same this year.

Net Worth.

The investor or household must have 1 million dollars in net worth OUTSIDE of their primary residence.

High Net Worth Individual (HNWI)

Outside the obvious, this term is generally a financial industry term for accredited investor

Edgar Database

A database of high-risk investments maintained by the SEC that is only accessible to Accredited investors and licensed brokerage or investment firms.

Financing Round

A round of financing or funding that is large enough to take an organization or project to the next major milestone. For how this works in film, check out the youtube video I’ve linked below, and the blog linked below that.

Related Video: The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Financing

Related Blog: The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Financing

Business Plan

A document written by an entrepreneur or filmmaker outlining their investment. In the film industry, this document will also often educate the investor on how the industry functions as a whole. This document is also known as a prospectus, but that term is not as commonly used as it once was.

Private Placement Memorandum (PPM)

A document that’s filed with the SEC for investors to consider investing in your project. Frequently an attorney will base this document off of the filmmaker or entrepreneur’s business plan. In most cases, a PPM will be registered with the aforementioned Edgar database for a modest filing fee.

Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Financial documents consisting of an expected income breakdown, cash-flow statement, and top sheet budget to be invaded in the business plan and function as the basis for many of the financial sections of other documents

The Three points above are heavily outlined in my business planning blog series.

Related: How to write an independent Film Business Plan (1/7)

Backed Debt

A secured loan backed by something like a tax incentive or pre-sale agreement.

Unbacked Debt

An unsecured loan, or debt without backing. Generally very high interest.

Financial Gap

The space between what you are able to raise and the amount you need to finish your project.

Financial Markets

A market where stocks, bonds, derivatives, or other securities are bought and sold. Common examples in the US would be the DOW and the NASDAQ.

Film Market

A convention where films are bought and sold primarily by sales agents and distributors. For more, check out the link below.

Related: What is a film market and how does it work?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The total value of all newly finished goods in a given country during a set timespan. Most commonly calculated on an annual basis.

Recession

A macroeconomic term signifying a period of a significant decline in economic activity. It’s generally only recognized after two consecutive quarters of down financial markets.

Depression

A severe recession that lasts longer than 3 years and corresponds with a drop in GDP of at least 10%

Bull Market

A market that’s strong and growing. It’s called a bull market as the upward trending graph looks like a bull nodding its head according to some people on Wall Street.

Bear Market

Yes, I spelled that right. It’s a financial market that’s going down, or staying stagnant. The name comes from a bear swiping its claws down. Probably the same wall street guy came up with it.

Thanks so much for reading! If you liked this, please make sure to check out last week’s general financing glossary, as well as my glossary of distribution terms. Also, please share. It helps A LOT.

Filmmakers Glossary of Business Terms

Additionally, make sure you grab my free Film Business Resource Package to get a print ready PDF version of all 3 glossaries.

Check the tags below for more related content.

Filmmakers Glossary of Film Business Terminology.

I’m not a lawyer, but I know contracts can be dense, confusing, and full of highly specific terms of art. With that in mind, here’s a glossary of Art. Here’s a glossary to help you out.

A colleague of mine asked me if I had a glossary on film financing terms in the same way I wrote one for film distribution (which you can check out here.) Since I didn’t have one, I thought I’d write one. After I wrote it, it was too long for a single post, so now it’s two. This one is on general terms, next week we’ll talk about film investment terms. As part of the website port, I’m re-titling the first part to a general film business glossary of terms, to lower confusion on sharing it. It’s got the same terms and the same URL, just a different title.

Capital

While many types exist, it most commonly refers to money.

Financing

Financing is the act of providing funds to grow or create a business or particular part of a business. Financing is more commonly used when referring to for-profit enterprises, although it can be used in both for profit and non-profit enterprises.

Funding

Funding is money provided to a business or non-profit for a particular purpose. While both for-profit and non-profit organizations can use the term, it’s more commonly used in non-profit media that the term financing is.

Revenue

Money that comes into an organization from providing shrives or selling/licensing goods. Money from Distribution is revenue, whereas money from investors is financing, and donors tend to provide funding more than financing, although both terms could apply.

Equity

A percentage ownership in a company, project, or asset. While it’s generally best to make sure all equity investors are paid back, so long as you’ve acted truthfully and fulfilled all your obligations it’s generally not something that you will forfeit your house over. Stocks are the most common form of equity, although films tend not to be able to issue stocks for complicated regulatory reasons and the fact that films are generally considered a high-risk investment.

Donation

Money that is given in support of an organization, project, or cause without the expectation of repayment or an ownership stake in the organization. Perks or gifts may be an obligation of the arrangement.

Debt

A loan that must be paid back. Generally with interest.

Deferral

A payment put off to the future. Deferrals generally have a trigger as to when the payment will be due.

“Soft Money"

In General, this refers to money you don’t have to pay back, or sometimes money paid back by design. In the world of independent film, it’s most commonly used for donations and deferrals, tax incentives, and occasionally product placement. It can have other meanings depending on the context though.

Investor

Someone who has provided funding to your company, generally in the form of liquid capital (or money.)

Stakeholder

Someone with a significant stake in the outcome of an organization or project. These can be investors, distributors, recognizable name talent, or high-level crew.

Donor

Someone who has donated to your cause, project, or organization.

Patron

Similar to donors, and can refer to high-level donors or financial backers on the website Patreon. For examples of patrons, see below. you can be a patron for me and support the creation of content just like this by clicking below.

Non-Profit Organizations (NPO)

An organization dedicated to providing a good or service to a particular cause without the intent to profit from their actions, in the same way, a small business or corporation would. This designation often comes with significant tax benefits in the United States.

501c3

The most common type of non-profit entity file is to take advantage of non-profit tax exempt status in the US.

Non-Government Organization (NGO)

Similar to a non-profit, generally larger in scope. Also, something of an antiquated term.

Foundation

An organization providing funding to causes, organizations and projects without a promise of repayment or ownership. Generally, these organizations will only provide funding to non profit organizations. Exceptions exist.

Grantor

An organization that funds other organizations and projects in the form of grants. Generally, these organizations are also foundations, but not necessarily.

Fiscal Sponsorship

A process through which a for-profit organization can fundraise with the same tax-exempt status as a 501c3. In broad strokes, an accredited 501c3 takes in money on behalf of a for-profit company and then pays that money out less a fee. Not all 501c3 organizations can act as a fiscal sponsor.

Investment

Capital that has been or will be contributed to an organization in exchange for an equity stake, although it can also be structured as debt or promissory note.

Investment Deck (Often simply “Deck”)

A document providing a snapshot of the business of your project. I recommend a 12-slide version, which can be found outlined in this blog or made from a template in the resources section of my site, linked below.

Related: Free Film Business Resource Package

Look Book

A creative snapshot of your project with a bit of business in it as well. NOT THE SAME AS A DECK. There isn’t as much structure to this. Check out the blog on that one below.

Related: How to make a look book

Audience Analysis

One of 3 generally expected ways to project revenue for a film. This one is based around understanding the spending power of your audience and creating a market share analysis based on that. I don’t yet have a blog on this one, but I will be dropping two videos about it later this month on my youtube channel. Subscribe so you don’t miss them.

Competitive Analysis

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. This method involves taking 20 films of a similar genre, attachments, and Intellectual property status and doing a lot of math to get the estimates you need.

Sales Agency Estimates

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. These are high and low estimates given to you by a sales agent. They are often inflated.

Related: How to project Revenue for your Independent Film

Calendar Year

12 months beginning January 1 and ending December 31. What we generally think of as, you know, a year.

Fiscal year

The year observed by businesses. While each organization can specify its fiscal year, the term generally means October 1 to September 30 as that’s what many government organizations and large banks use. Many educational institutions tie their fiscal year to the school year, and most small businesses have their fiscal year match the calendar year as it’s easier to keep up with on limited staff.

Film Distribution

The act of making a film available to the end user in a given territory or platform.

International Sales

The act of selling a film to distributors around the world.

Related: What's the difference between a sales agent and distributor?

Bonus! Some common general use Acronyms

YOY

Year over Year. Commonly used in metrics for tracking marketing engagement or financial performance on a year-to-year basis.

YTD

Year to Date. Commonly used in conjunction with Year over year metrics or to measure other things like revenue or profit/loss metrics.

MTD

Month to Date. Commonly used when comparing monthly revenue to measure sales performance. Due to the standard reporting cycles for distributors, you probably won’t see this much unless you self-distribute.

OOO

Out of Office. It generally means the person can’t currently be reached.

EOD

End of Day. Refers to the close of business that day, and generally means 5 PM on that particular day for whatever the time zone of the person using the term is working in.

Thanks for reading this! Please share it with your friends. If you want more content on film financing, packaging, marketing, distribution, entrepreneurialism, and all facets of the film industry, sign up for my mailing list! Not only will you get monthly content digests segmented by topic, but you’ll get a package of other resources to take you film from script to screen. Those resources include a free ebook, whitepaper, investment deck template, and more!

Check the tags below for more related content!

When and Where to use Each Indiefilm Investment Document

Most Sales agents don’t want your business plan, and a bank doesn’t want your lookbook. Here’s what stakeholders do want, and when.

There are 3 different documents you would need to approach an investor about your independent film. I’ve written guides on this blog to show you how to write each and every one of them. Those three documents are a Look Book (Guide linked here.) a Deck (Guide Linked Here) and a business plan. (Part 1/7 here) But while I’ve Written about HOW to create all of these documents, I’ve held back WHY you write them, WHO needs them, and WHEN to use them. So this blog will tell you WHO needs WHAT document WHEN and HOW they’re going to use it.

As with some other blogs, I’ll be using the term stakeholder to refer to anyone you may share documents with, be they an investor, studio head, sales agent, Producer of Marketing and Distribution (PMD) or Distributor.

What are these documents and WHY do you share them?

So first, let’s start with what each document is, just in case you haven’t read the other blogs (which you still should)

A Look book for an independent film is an introductory document, that’s very pretty and engaging and gives an idea of the creative vision of the film. The purpose is to get potential stakeholders interested enough in the project to request either a meeting or a deck. The goal in showing them this document is to get them to start to see the film in their head and get them to become interested in the project on an emotional level.

Related: Check out this blog for what goes into a lookbook

A Deck is a snapshot of the business side of your film. The goal is to send them something that they can review quickly to get an idea of how this project will go to market and how it will make money so that they get an idea of how they’ll get their money back.

Related: The 12 Slides you need in your indie film investment Deck

A business plan is a detailed 18-24 page document broken into 7 sections that will give potential investors not only an idea of your investment but of the industry as a whole. In a sense, it’s equal parts education and persuasion, especially for investors new to the film industry. The goal is to give the prospective stakeholder a deeper understanding of the film and media industry, and a very thorough understanding of your project and the potential for investing in it.

Related: How to Write an Indiefilm Business Plan (1/7 - Executive Summary)

WHO needs these documents and HOW they’ll use it

Different stakeholders need these documents at different times.

Look Books should be sent to any potential stakeholder, including investors, studio heads, sales agents, distributors, producer’s reps, Executive Producers, and more. It’s a creative document that gives a good idea of the product at the early stage. It helps people gauge interest in your project

Decks are primarily used by Investors, Executive Producers, PMDs, and potentially Sales Agents. Distributors and Studio Heads are less likely to need a deck since they know the business better than you do. At least most of the time.

Business plans are primarily needed by angel investors new to the film industry and Angel Investment Syndicates to use as the backbone for the Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) The First and last sections of the business plan (The Executive Summary and Pro-Forma Financial Statements) may be more widely used, often at the same general place as the deck, or only shortly after.

WHEN do they need these documents?

Look books come early on. It’s generally the first thing they’ll ask for when considering your project.

Decks come shortly after the lookbook. Sometimes in an initial meeting, or sometimes directly after that first meeting.

Looking at a business plan is generally very deep in the process of talking to a potential stakeholder, it’s almost always after at least 2-3 meetings and a thorough review of the deck.

If this was useful, you should definitely grab my free film business resource packet. It’s got templates for some of these documents, a free e-book, a whitepaper that will help you write these documents, as well as monthly blog digests segmented by topics about the film business so you can sound informed when you talk to investors. Click the button below to grab it right now.

Check out the tags for related content.

How to Make LookBook for an Independent Film

Decks and lookbooks are not the same. Here’s how you make the latter.

I’ve written previously about what goes into an indie film deck, but as I get more and more submissions from filmmakers, I’m realizing that most of them don’t fully understand the difference between a lookbook and a deck. So, I thought I would outline what goes into a lookbook, and then I’ll come back in a future post to outline when you need a lookbook when you need a deck, and when you need a business plan.

What goes in a lookbook is less rigid than what goes in a deck. It’s also designed to be a more creatively oriented document than a deck. But in general, these are the pieces of information you’ll need in your lookbook. I’ve grouped them into 4 general sections to give you a bit more of a guideline.

You’ll often see the term stakeholder. I use this to mean anyone who might hold a stake in the outcome of your project, be they investors, distributors, or even other high-level crew.

Basic Project Information

This section is to give a general outline of the project and includes the following pieces of information.

Title

Logline

Synopsis

Character Descriptions

Filmmaker/Team bios

The title should be self-explanatory, but if you have a fancy font treatment or temp poster, this would be a good place to use it.

The logline should be 1 or 2 sentences at most. It should tell what your story is about in an engaging way to make people want to see the movie. You probably want to include the genre here as well,

The synopsis in the lookbook should be 5-8 sentences, and cover the majority of the film’s story. This isn’t script coverage or a treatment. It’s a taste to get your potential investors or other stakeholders to want more.

Character descriptions should be short, but more interesting than basic demographics. Give them an heir of mystery, but enough of an idea that the reader can picture them in their head. Try something like this. Matt (white, male, early 20s) is a bit of a rebel and a pizza delivery boy. He’s a bit messy, but nowhere near as bad as his apartment. He’s more handsome than his unkempt appearance lets on, If he cleaned up he’d never have to sleep alone. But one day he delivers pizza to the wrong house and gets thrust into time-traveling international intrigue.

Even that’s a little long, but I wasn’t actually basing it on a movie, so tying it into the film itself was trickier than I thought it would be. That would be alright for a protagonist, but too long for anyone else.

Filmmaker and Team bios should be short, bullet points are good, list achievements and awards to put a practical emphasis on what they bring to the table DO NOT pad your bio out to 5000 words of not a lot of information. Schooling doesn’t matter a lot unless you went to UCLA, USC, NYU or an Ivy League school.

Creative Swatches

These are general creative things to give a give the prospective stakeholder an idea of the creative feel of the film. They can include the following, although not all are necessary.

Inspiration

Creatively Similar Films

Images Denoting the General Feel of the Film

Color Palette

The inspiration would be a little bit of information on what gave you the vision for this film. It shouldn’t be long, but it definitely shouldn’t be something along the lines of “I’ m the most vissionnarry film in the WORLD. U WILL C MAI NAME IN LAIGHTS!” (Misspellings intentional) Check your ego here, but talk about the creative vision you had that inspired you to make the film. Try to keep it to 3-4 sentences.

Creatively similar films are films that have the same feel as your film. You’re less restricted by budget level and year created here than you would be in a comp analysis, that said, don’t put the Avengers or other effects-heavy films here if you’re making an ultra-low budget piece. I’d say pick 5, and use the posters.

Images denoting the general feel of the film are just a collection of images that will give potential stakeholders an idea of the feel of the film. These can be reference images from other films, pieces of art, or anything that conveys the artistic vision in your head. This is not a widely distributed document, so the copyright situation gets a bit fuzzy regarding what you an use. That said, the stricter legal definition is probably that you can’t use without permission. #NotALawyer

The color palette would be what general color palette of the project. This is one you could leave out, but if there’s a very well-defined color feel of the film like say, Minority Report, then showing the colors you’ll be using isn’t a terrible call, Also,, it's generally best to just let this pallet exist on the background of the document on your look book.

Technical/ Practical swatches

This section is a good indicator of what you already have, as well as some more technical information about the film in general. It should include the following.

Locations You’d like to shoot at

Cities You’d Like to shoot in

Equipment you plan on using

Photos are great here, if you use cities or states include the tax incentives for them, The equipment should only be used if it’s the higher end like an Arri or Red. If you’re getting it at a fantastic cost, you should mention that here as well. People tend not to care about the equipment you’re using, but if you’re going to put it in any pitch document, this is the one.

Light Business Information

The lookbook is primarily a creative document, but since most of the potential stakeholders you’re going to be showing it to are business people, you should include the basics. When they want more, send them a deck.

Here’s what you should include

Ideal Cast list & Photos

Ideal Director List

Ideal Distributors

These are important to assess the viability of the project from a distribution standpoint. It can also affect different ways to finance your film. If your director is attached, don’t include that. If you have an LOI from a distributor, don’t mention potential distributors. Unless your film is under 50k, don’t say you won’t seek name talent for a supporting role. You should consider it if it’s even remotely viable.

If this was useful to you but you need more, you should snag my FREE indiefilm resource package. I’ve got lots of great templates you get when you join, and you also get a monthly blog digest segmented by topic to make sure you’re informed when you start talking to investors. Click below to get it.

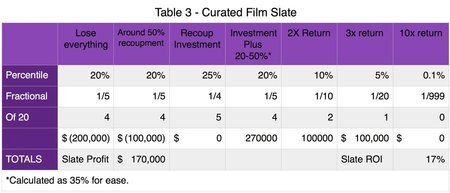

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 7/7 Pro-Forma Financial Statements

If you want an ivestor to give you their money, you’ll need to show them how you’ll spend it and how they’ll get it back. That’s what pro-forma financial statements are for. Here’s how you make them.

In the final part of my 7-part series on writing a business plan for independent film and media, I’ll be going over all of the financial statements you’ll need in your business plan. This is a section that you’ll want to write before you write the financial text section of your plan, as it will have a great impact on that section and potentially other sections of the plan. Each document should take up only a single page.

Topsheet Budget

If you’re reading this, hopefully, you already know what a topsheet budget is. In case you don’t, It’s the summary budget of your entire film that should take up no more than a page. Unlike the rest of these documents which should be made by an executive producer, the top sheet budget is best made by a line producer or UPM. It’s important to note, that you can’t just make a topsheet budget, it comes as a byproduct of making a detail budget for your film. It’s not something that should be effectively created for it’s own sake.

Revenue Topsheet

This page is a summary of all the money that will come into your project, and how it will go out and come back to the production company and the investor, loosely organized by what comes in domestically vs internationally, and what media right types bring in what money.

This is not something that all people writing business plans for films include, however, I feel that it’s an important document that gives an angel investor a simplified snapshot of the entire revenue picture before diving into some of the more gory details.

Waterfall to Company (Expected Income Breakdown)

Louise Levison says you only need an expected income breakdown. When I create proformas, I tend to include how the overall revenue table that outlines where the money will be divided among the major stakeholders. This includes the distribution platforms, distributors, sales agents, producer’s reps, banks, and investors. It’s likely that if this is your first film, you won’t have all of those stakeholders, but it’s important to include the stakeholders you do have.

Additionally, I use this outline what cuts are standard for each of those stakeholders, and what remains from each right type to go to the production company and the investor.

Internal Company Waterfall/Capitalization Table

This is another document that not everyone includes, but due to my time in the tech industry, I find something like it is essential. The term capitalization table (or Cap Table for short) is taken from the tech industry and outlines who owns what part of a company.

This document goes further than a standard cap table, in that not only does it outline the major owners of the company, it also shows where the money goes once it comes back to the production company, and how it’s divided between debt, investors, producers, actors, and other people within your production company who made the film.

This document should calculate the investor’s expected Return on Investment (ROI) as well as how much is likely to go to producers and anyone else who has received profit participation. If you have more than one set of people on the crew receiving profit participation, then you may want to lump it into a cast/crew equity pool.

CashFlow Statement/Breakeven Analysis

This is a yearly/quarterly estimate of how the money will go out and come back in. Generally, your entire budget will go out before any money comes back in. If you’re using staged investments, you’ll want to outline when additional rounds of funding are likely to come into the company. Part of this is keeping track of the cash flow as you spend the money and as it goes back to investors.

I’ll generally make an assumption that it will take a year from investment to complete the film. After that, money will start coming back in about 3-4 quarters, and trickle in from each source according to however you think the film will be windowed. That’s actually the optimistic version timeline. By the end of 5-7 years after the initial investment, you’ll likely just want to end the cash flow statement since it’s unlikely your film will be producing that much revenue. Films are not evergreen.

Research/Sources

This is as it sounds. it’s all the resources for your comparative analysis that you used to make revenue projections, as well as any other sources you may have referenced in your plan. If you did a comparative analysis, you’ll want to include the details on the films you chose as well as where you got the data, as reporting is inconsistent across major platforms like IMDb pro, The-Numbers, Box Office Mojo, and Rentrack. I also have a useful whitepaper and some useful links in the resource pack.

Thanks so much for reading this blog. Thanks even more if you read all 7 parts! If you’re a film school teacher and would like to use this in a course, feel free to email me using the link below to get a free print-ready version of this series, or anything else you may want to reverence.

Making your pro-forma financial statements requires a lot of research. My resource package has a whitepaper and collection of links that will help speed that process up a bit, as well as other templates and related content. Grab it for free with the button below.

If you need a guiding hand through the process, I’ve written. few dozen plans. Check out my services page if this is just. a bit too daunting to do on your own.

Lastly, if you want to review any of the other sections of this 7 part series, here’s a guild for you below.

Executive Summary

The Company

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements. (This Section)

Check out the tags below for related content.

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 6/7 Financial Methodolgy

If you want to raise money from investors to make your independent film, you’ll need rock-solid financials. Here’s how you write that section of your business plan.

In part 6 of my 7-part series on independent film business planning, we’re going to go over the text portion of the financial section of the business plan. This is where you explain the methodology you used in your financial projections, the general plan for taking in the money, and then an overview of what you’re going to present in the final section, the pro-forma financial statements.

It’s pretty common to send this section out as a standalone document, or perhaps paired with the deck or executive summary. That said, the reason it’s at the back of the business plan is to force your potential investor to flip around through the plan and better acquaint themselves with your prospectus and project. That, and this is relatively standard practice across multiple industries.

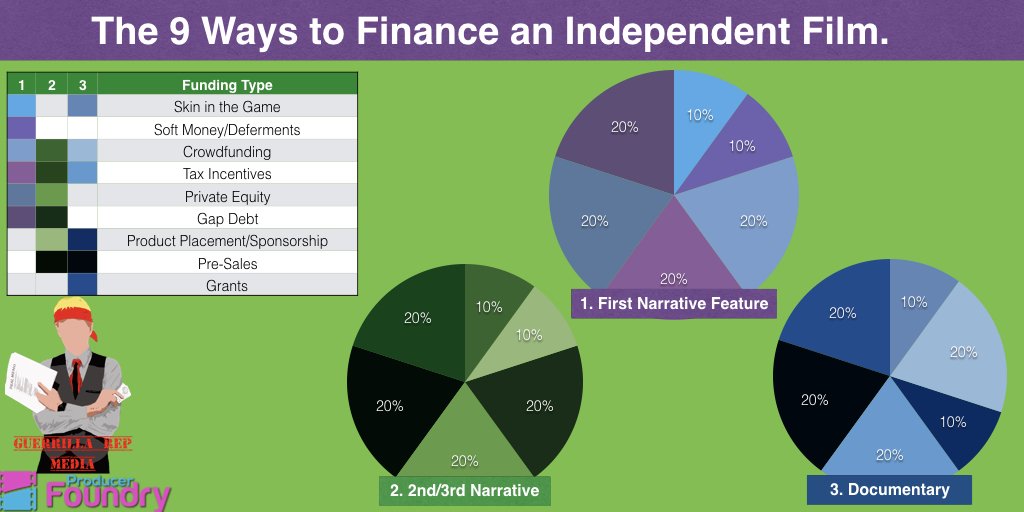

Investment Plan

This subsection is devoted to how you intend to raise your funding. As a hint, the answer SHOULD NOT be that you intend on raising your funding entirely from equity investors. You’ll want to outline where you intend to raise each part of your money from, as well as how that money will be raised.

Some questions to ask yourself here are as follows, how much are you planning on raising in tax incentives? How much are you planning on raising in product placement? Do you have any pre-sales from a distributor or sales agency? Are you planning on any other forms of backed debt? Did you have a successful crowdfunding campaign? How much are you looking for in equity investment? And how much do you intend to raise in unbacked debt?

For more detail on this, you should check out one of my most popular articles.

Related: The 9 ways to finance an independent film.

You’ll also want to figure out if you’re staging the investment. By this, I mean are you planning on raising money for development first? Do you plan a separate raise for completion or marketing funds? There can be some pretty big advantages to raising funding for your film across multiple rounds.

For more information on this, I encourage you to check out my blog on the 4 stages of independent film investment.

Related: The 4 stages of independent film investment.

You absolutely must to make sure they understand your offer. Some questions you’ll need to answer are: What’s the amount you’re raising in equity and what percentage ownership in your project are you offering for that funding? What’s your minimum buy-in? Who are the other stakeholders?

Additionally, you’ll want to highlight the potential revenue for your film and give them their estimated Return on Investment (ROI). This will have to be done after your pro-forma financial statements. You’ll also want to outline when you expect them to break even.

Financial Assumptions

This section is primarily about outlining the assumptions you used while making your pro-forma financial statements. You’ll want to outline the criteria you used when creating a comparative analysis, as well as what assumptions you made while creating your cash flow sheet, and waterfall to your company/expected income breakdown.

For more detail on financial projections, please check out this blog below.

Related: The two main types of financial projections

Pro Forma Financial Statements

Finally, you’ll want to outline your Pro-Forma financial statements. For reference, these are the following documents.

Topsheet Budget: A snapshot of how the money will be spent on your film. You can only get this by doing a full detail budget. If you try to make a top sheet from scratch, you’ll end up creating more problems than you solve.

Revenue Topsheet: An overview of money to the company and to the investor.

Waterfall to Company/Expected Income breakdown: An outline of how much money your film will make based on your comparative analysis, and from what sources. Generally, when I make a waterfall like this, I’ll also deduct the fees from various other stakeholders including platforms, distributors, sales agents, and producer’s reps (if applicable.)

Internal company waterfall (capitalization table). This sheet is something that not everyone does, but it essentially outlines where the money will go once it gets to your company. I feel this is necessary if you’re using a more complicated financial mix that incorporates debt and tax incentives.

Cashflow Sheet/ Breakeven analysis: This document is an overview of how money will flow through the company and subsequently come back in. you’ll want to highlight when they can expect to recoup their investment.

Research/Sources: This is self-explanatory, it’s the research you used in the other sections of the plan, particularly the films you used in the comparative analysis.

Thanks so much for reading! I’ll be back next week with the final installment going into much more detail on the pro forma financial statements.

The reason I was able to write this blog series is that I’ve written a few dozen independent film business plans. If you need help with yours, you should check out my services page.

If you need more help researching for your business plan, check out the indiefilm Business Resource Pack. As mentioned above, it’s got a whitepaper to help you with your research, as well as lots of other helpful links and resources to aid in the creation of all the documentation you’ll need to talk to your investors. Plus, you’ll get a monthly blog digest full of helpful content so that you can be as knowledgeable as possible when you speak to your investor contacts.

Finally, if you want to check out the other sections of this 7 part blog series, I’ve included a table of contents below.

Executive Summary

The Company

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financial Section (Text/Methodology) - This Post

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

Check the tags below for related conent!

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 5/7 SWOT/ Risk Analysis

Investing is always risky. Investing in Film is moreso. If you’re raising money, you need to make sure your investors know this.

In part 5 of my 7-part series on business planning, we talk about the risk management/SWOT Analysis of your project. It begins with a risk statement that goes into exactly why film is a highly speculative and inherently risky investment, and then goes into a SWOT Analysis that illustrates how you plan on managing those risks. For those of you who don’t know SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

Risk Statement

This is a boilerplate legal copy that you should not write yourself. You’ll need a lawyer to write it, or some editions of Filmmakers and Financing by Louise Levinson have a statement you can use. You’ll see it in the related books section below. The purpose of this statement is to ensure that any potential knows that film investment carries a fairly significant risk of losing everything you put into it.

This is something you MUST include in order to not paint too blue a sky, or make false promises. If it scares off any investors, it’s probably better you didn’t work with them anyway.

SWOT Analysis

The way I do my SWOT analysis is on the bottom third of the page that contains the risk statement, I do a 2*2 grid of strengths weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that outlines everything that will come for the following pages. If it fits, this is succinct and a great way to manage space while informing your people.

The other four sections of this plan are things I generally dress in a format similar to an outline, starting with a restatement of the Strength, Weakness, opportunity, or threat itself, and then stating how I intend to mitigate the negative and capitalize on the positive. Here’s an outline of what each of these parts of the acronym stands for.

Strengths

Strengths are good things that are inherent to your project. This could be something like holiday movies tend to have longer lifespans because they have regular movies to trigger people feeling the need to watch them, or there’s already an existing fan base for the intellectual property you’ve optioned. Another good thing to focus on would be the track record of your team, and the general stength of any marketable attachments you’ve gotten. If you don’t have any of those, there’s an article on it in the free ebook in the resouce pack.

Weaknesses

Conversely, weaknesses are things inherent to your project that may represent a problem. These could be things like the Fourth of July is a uniquely American Holiday, so the film may be difficult to sell internationally. It could also be something like, the film is completely original and has no existing fanbase. As previously stated, you’ll want to add exactly how you plan on addressing any weaknesses below each one.

Opportunity

While Strengths are inherent to your project, opportunities are more related to the current state of the overall market. This could be a marketable attachment you’ve got that just had a big win, such as one of your cast being cast in a major show or movie that was just announced.

Another example of this might be that there aren’t enough Fourth of July movies currently being made to sate demand and you’ve budgeted your film such that you can make your money back domestically.

Another example would be that a book from the same author as the book we’ve based our script on just got picked up for a television series by *insert name of the studio or PayTV Channel.*. Similarly, if your story is inspired by current conditions going on in the world or targeting a growing audience this is a good place to hammer that point home.

Threats

Just like opportunities, threats are reflective of current market conditions. An example of a threat would be that due to the current geopolitical state of the world, many foreign countries are less likely to buy American than they used to be. A potential trade war would also be considered a threat, although as of right now that’s not incredibly likely to effect to film and media. Without being too political, many threats you’ll need to understand are a result of macroeconomic conditions that you can only really track by being politically aware.

Thank you SO much for reading! I do a lot of this sort of work with my clients, so if you have a direct question that you need help answering for your business, then check out the Guerrilla Rep Services page.

If you like the content, you should grab my free film business resource package You’ll get great research aides and a whitepaper on the state of the industry, you’ll also get a free e-book, money and time-saving resources, templates, monthly digests of content like this segmented by topic, plus a whole lot more. Link in the button below.

Finally, this is part 5 of a 7 part series. Next week we’ll be tackling the financial text section, and then we’ll round it out with proforma financial statements the following week. In the meantime, check out the other parts of the series with the links below.

Executive Summary

The Company

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis (This Section)

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 4/7 Marketing Section

If you want to raise money from investors, you’re going to need a plan. A business plan, to be exact. Here’s how you write the marketing section.

In this installment of my 7 part blog series on business planning, we’re going to take a look at the marketing section of the plan. This section is likely to be the longest section, as it encompasses an overview of the industry, as well as both marketing and distribution planning. Generally, this section will encompass 3-5 pages of the plan, all single-spaced. This is among the most important sections of the plan, as it is a real breakdown of how the money will come back to the film

Industry

In this subsection, you’ll want to define some key metrics of the film industry. You’ll want to include its size, how much revenue it brings in, and ideally an estimate of how many films are made in a year, as well s the size of the independent part of the film industry vs the overall film industry. If you want help with some of those figures, you should look at the white paper I did with ProductionNext, IndieWire, Stage32, and Fandor a few years back. To the best of my knowledge, it’s still among the most reliable data on the film industry.

The fact that the film industry is considered a mature industry that is not growing by significant margins is also something you’ll also want to mention. You’ll also want to talk about the sectors of growth within the film industry, as well as where the money tends to come from for independent producers, and a whole lot of other data you’re going to have to find and reference. As mentioned above, the State of the Film Industry book linked in the banner below has much of this information for you.

Overall, this section should be about a page long. The best sources for Metrics are the MPA THEME report and the State of The Film Industry Report. You can find links or downloads of both of those in my free resource pack.

Marketing

The marketing subsection of the plan goes into detail about both the target demographics and target market of your film, as well as how you plan on accessing them. To quote an old friend and long-time silicon valley strategist Sheridan Tatsuno, Finding your target market is like placing the target, and marketing is like shooting an arrow. For more detail on how to go about finding your target market, I encourage you to check out the blog below, as my word count restrictions will not let me go too deeply into it here

Related: How do I figure out who to sell my movie to?

Figuring out how you’re going to market the film can be a challenge for many filmmakers. Generally, I’d advise putting something more detailed than “smart social media strategy.” I tell most of my clients to focus on getting press, appearing on podcasts, and getting reviews. Marketing stunts can be great, but timing them is difficult to pull off.

All of this being said, you’ll need more to your marketing strategy than simply going to festivals to build buzz. The marketing category at the top of this blog, as well as the audience, community, and marketing, tags at the bottom of the page, are a good place to start.

Distribution

This section talks about how you intend to get your film to the end user. This section should be an actionable plan on how you intend to attract a distributor. This section should not be “We’ll get into sundance and then have distributors chasing us!” I hate to break it to you, but you’re probably not going to get into Sundance. Fewer than 1% of submissions do.

The biggest thing you need to answer is whether you plan on attaching a distributor/sales agent or whether you intend to self-distribute. if you’re not sure, this blog might help you decide. There’s lots more to it, I’d recommend checking the distribution category or the international sales tag on this site to learn more of what you need to write this section.

Related: 6 questions to ask yourself BEFORE self distributing your indiefilm

Somewhere between a quarter and a third of all the blogs on this site are devoted to distribution, so there’s lots of stuff here for you to use when developing this plan. If you want to develop more of a plan than distributing it yourself, it’s also something I’d be happy to talk to you about it. Check out my services page for more.

If that’s a bit too much for you but you still want more information about the film business, check out my film business resource package. You’ll get a free e-book, monthly digests segmented by topic, and a packet of film market resources including templates and money-saving resources.

This is part of a 7 part series. I’ll be updating the various sections as they drop. So check back and if you see a ling below, it will take you to whatever section you most want to read.

Executive Summary

The Company

The Projects

Marketing (This post)

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-forma Financial Statements.

Check the tags for more content!

How To Write a Business Plan for an Independent Film - 3/7 Project(s)

Filmmakers don’t tend to plan to fail, but they often fail to plan. Here’s how to write the project section of an independent film business plan.

Next up in my 7 part series on writing a business plan for independent film, we’ll be taking a deeper look at the project(s) section of the plan. The projects section of the plan is the most creative section, as it talks about the creative work that you’re seeking to finance. That being said, it breaks those creative elements into their basic business points. This section should be no more than a page if you have one project, and no more than 2 pages if you’re looking at a slate.

GENRE

Genre is a huge part of marketing any film. It essentially categorizes your film into what interest groups you’ll be marketing. This subsection should focus on the genre of your film, as well as who you expect the film to appeal to.

For more information on the concept of Genre in Film as it pertains to distribution, check out this blog.

RELATED: WHY GENRE IS VITAL TO INDIEFILM MARKETING & DISTRIBUTION

PLOT SYNOPSIS

This is as it sounds. It’s a one-paragraph synopsis of your film. When you’re writing it, keep in mind that you’re not telling your story, so much as selling it. Make it exciting. Make it something that the person reading the plan simply will not be able to ignore.

BUDGET

This one should also be self-explanatory, list the total budget of your film. It would make sense to break it into the following categories. Above the Line, Development, Pre-Production, Principle photography, post-production, and producer’s contribution to marketing and distribution.

The last part is to acknowledge that while the distributor will be contributing a large amount to the marketing and distribution costs of the film, it will not be the sole contribution, and you as the filmmaker will likely have to contribute some amount of time and/or money to make sure your film is sold well.

RATING

This section talks about your expected rating. Say what you expect to get, what themes you think will cause the film to get that rating, and how that will help you sell the film to the primary demographic listed above.

MARKETABLE ATTACHMENTS

Did you get Tom Cruise for your movie? What about Joseph Gordon Levitt? Or maybe Brian De Palma came on to direct. If you have anyone like this (or even someone with far less impressive credits) make sure you list that you’ve got them. If you’re in talks with their people, list it here too.

Related: 5 Reasons you Still need Name Talent in your film

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY STATUS

Finally, you’ll need to list the intellectual property status of your film. By this, I simply mean is the concept original? Is it based on anything? Did you acquire the rights to whatever it’s based on? If you optioned rights, when does the option expire? If you optioned rights, who is the original owner of the rights?

Writing a business plan that can actually raise funding is a lot more than just using a template. If you want a leg up you should check out my free resource pack which includes a deck template, a free e-book, digests of relevant industry-related content, delivered to your inbox once a month, and notifications of special events and other announcements tailored to the needs of the filmmakers I work with.

You should know that I’ve written a few dozen business plans for filmmakers, some of which have raised significant funding. If you want to talk about it check out our services page.

Thanks so much for reading! You can find the other completed sections of this 7-part series below.

Executive Summary

The Company

The Projects (This Post)

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

Check the tags below for related content

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 2/7 Company Section

One of many things you’ll probably need to finance an independent film is a business plan. Here’s an outline of one of the sections you’ll need to write.

Last time we went over the basics of writing an independent film executive summary. This time, we’re diving into the first section of a business plan. By this I mean the company section. If you want an angel investor to give you money, they’re going to need to understand your company. There are some legal reasons for this, but most of it is about understanding the people that they’re considering investing in.

The company section generally consists of the following sub-sections. This section only covers the company making the film, not the media projects themselves. Those will be explored in section III - The Projects.

FORM OF BUSINESS OWNERSHIP

This is the legal structure you’ve chosen to form your company as. If you have yet to form a company, you can tell an investor what the LLC will be formed as once their money comes in. I’ve written a much longer examination of this previously, which I’ve linked to below. Also, I’m Not a Lawyer, that’s not legal advice, don’t @ me.

Related: The Legal Structure of your Production Company

THE COMPANY

This subsection talks a bit about your production company. You can talk about how long you’ve been in business, what you’ve done in the past, and how you came together if it makes sense to do so. Avoid mentioning academia if at all possible, unless you went to somewhere like USC, UCLA, NYU, or an Ivy League School. Try to make sure this section only takes up 2-3 lines on the page.

BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY

This is what you stand for as a company. What’s your vision? What content do you want to make over the long term? Why should an investor back you instead of one of the other projects that someone else solicited?

Your film probably can’t compete with the potential return of a tech company. I’ve explored that in detail over the 7 part blog series linked below.

Additionally, you might want to check out Primal Branding by Patrick Hanlon it’s a great book to help you better understand how to write a compelling company ethos. I use it with clients as it frames it exceptionally well for creative people. That is an affiliate link.

Related: Why don’t rich Tech people invest in film?

Since you can’t compete on the merits of your potential revenue alone, you need to show them other reasons that it would behoove them to invest in your project. See the link below for more information.

Related: Diversification and Soft Incentives

PRODUCTION TEAM

These are the key team members that will make your film happen. List the lead producer first, the director second, the Executive Producer second, and the remaining producers after that. Directors of photography and composers tend to not add a lot of value in this section, but if you’ve got one with some impressive credits behind them, it might make sense to add the.

Generally, if you have someone on your team with some really impressive credits, it might make more sense to list them ahead of the order I listed above.

Essential Reference Books for Indiefilm Business Planning

PRODUCT

This should talk a little about the films you’re going to make, and the films you’ve made in the past.

OPERATIONS

This is a calendar of operations with key milestones that you intend to hit during the production of the film. These would be things like:

Financing Completed

Preproduction Begins

First Day of Principle Photography

Completion of principal Photography

Start of post-production

You’ll also want to include when you intend to finish post-production, as well as when you intend to start distribution, but that should be less specific than the items listed above. For the non-bullied items, I would say that you should just give a quarter of when you expect to have them happen, whereas the bullets should be a month or a date.

CURRENT EVENTS

The Current events are as they sound, a list of the exciting events going on with your film and with your company. This could be securing a letter of intent from an actor, director, or distributor, completing the script, or raising some portion of the financing.

Assisting filmmakers in writing business plans is a decent part of the consulting arm of my business. The free e-book, blog digests, and templates in my resource package can give you a big leg up. That said, If this all feels like a bit much to do on your own you might want to check out my services page. Links for both are in the buttons below.

Thanks so much for reading! You can find the other completed sections of this 7 part series below

Executive Summary

The Company (This One)

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-forma Financial Statements.

Check the tags for more related content.

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 1/7 Executive Summary

If you want to raise money from an investor, you have to do your homework. That includes making a business plan. A business plan starts with an executive summary.

One of my more popular services for filmmakers is Independent Film Business Plan Writing. So I decided to do a series outlining the basics of writing an independent film business plan to talk about what I do and give you an idea of how you can get started with it yourself.

Before we really dive in it’s worth noting that what will really sell an investor on your project is you. You need to develop a relationship with them and build enough trust that they’ll be willing to take a risk with you. A business plan shows you’ve done your homework, but in the end, the close will be around you as a filmmaker, producer, and entrepreneur.

The first Section of the independent film business plan is always the Executive Summary, and it’s the most important that you get right. So how do you get it right? Read this blog for the basics.

Write this section LAST

This section may be the first section in your independent film business plan, but it’s the last section you should write. Once you’ve written the other sections of this plan, the executive summary will be a breeze. The only thing that might be a challenge is keeping the word count sparse enough that you keep it to a single page.

If you have an investor that only wants an executive summary, then you can write it first. But you’ll also need to generate your pro forma financial statements for your film, and project revenue and generally have a good idea of what’s going to go into the film’s business plan in order to write it. I would definitely write it after making the first version of your Deck, and rewrite it after you finish the rest of the business plan.

Keep it Concise

As the name would imply, the Executive Summary is the Summary of an entire business plan. It takes the other 5 sections of the film’s business plan and summarizes them into a single page. It’s possible that you could do a single double-sided page, but generally, for a film you shouldn’t need to.

A general rule here is to leave your reader wanting more, as if they don’t have questions they’re less likely to reach out again, which gives you less of a chance to build a relationship with them.

Here’s a brief summary of what you’ll cover in your executive summary.

Project

As the title implies, this section goes over the basics of your project. it goes over the major attachments, a synopsis, the budget, as well as the genre of the film. You’ll have about a paragraph or two to get that all across, so you’ll have to be quite concise.

Company/Team

This section is a brief description of the values of your production company. Generally, you’ll keep it to your mission statement, and maybe a bit about your key members in the summary.

Marketing/Distribution

In a standard prospectus, this would be the go-to-market strategy. For a film, this means your marketing and distribution sections. For the executive summary, list your target demographics, whether you have a distributor, plan to get one, or plan on self-distributing. Also, include if you plan on raising additional money to assist in distribution.

SWOT Analysis/Risk Management

SWOT is an acronym standing for Strengths Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. For the executive summary, this section should include a statement that outlines how investing in film is incredibly risky, due to a myriad of factors that practically render your projections null and void. Advise potential investors to should always consult a lawyer before investing in your film. Cover your ass. I’ve done a 2*2 table with these for plans in the past, and it works reasonably well. Speaking of covering one’s posterior, you should have a lawyer draft a risk statement for you. Also, I am not one of those, just your friendly neighborhood entrepreneur. #NotALawyer #SideRant

Financials

Finally, we come to the part of the plan that the investors really want to see. How much is this going to cost, and what’s a reasonable estimate on what it can return? There are two ways of projecting this, outlined in the blog below.

Related: The Two Ways to Project Revenue for an independent film.

In addition to your expected ROI, you’ll want to include when you expect to break even and mention that pro forma financial statements are at the end of this plan included behind the actual financial section.

Pro Forma Financial Statements.

If you’re sending out your executive summary as a document unto itself, you will strongly want to consider including the pro forma financial statements. For Reference, those documents are a top sheet budget, a revenue top sheet, a waterfall to the company/expected income breakdown, an internal company waterfall/capitalization table, a cashflow statement/breakeven analysis, and a document citing your research and sources used in the rest of the plan.

Writing an executive summary well requires a lot of highly specialized knowledge of the film business. It’s not easy to attain that knowledge, but my free film business resource package is a great place to start! You’ll get a deck template, contact tracking templates, a FREE ebook, and monthly digests of blogs categorized by topic to help you know what you’ll need to have the best possible chance to close investors.

Here’s a link to the other sections of this 7 part series.

Executive Summary (this article)

The Company

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

5 Rules for Finding Film Investors

If you want to make a movie, you need money. If you don’t have money, you probably need investors. Here’s how you find them.

One of the most common questions I get is where to find investors for a feature film. Inherent in that question is simply where to find investors. While I may not have a specific answer for you regarding exactly where to find them, I do have a set of rules for figuring out where you might be able to find them in your local community. This is meant to be applicable outside of the major hubs in the US, and as such it’s not going to have to be more of a framework than a simple answer.

Would you rather watch or listen than Read? Here's the same topic on my YouTube Channel.

Like and Subscribe!

1. Go where the money is.

Think about where people in your community who have money congregate. In San Francisco, the money comes from tech. In Colorado, the money came from oil, gas, and tourism, but has recently grown to include legal recreational marijuana. In many communities, some of the most affluent are the doctors and medical professionals. In most communities, the local lawyers tend to have money, but you’ll have to make sure you come prepared. Figure out what industries drive your local economy and then extrapolate from that who might have enough spare income to invest in your project.

If you know what these people do, then you can start to figure out where they go when it’s after working hours. If you know where they go after hours, you can go get a drink and start to work your way to making a new friend in this investor.

All that being said, Be careful not to solicit too early, as that can actually be illegal. #NotALawyer.

2. Figure out a place where you can find something in common

Any investment as inherently risky and a-typical as the film industry relies heavily on your relationship with your investor. As such, finding something you have in common is a great way to start the relationship right.

RELATED: 7 Reasons Courting an Investor is Like Dating

As an example of what I mean, I’ve met investors while singing karaoke at Gay bars in San Francisco. I’ve met others at industry events, and I’ve even met a few by going to some famous silicon valley hot spots where investors and Venture Capitalists are known to congregate. If you know where all the doctors go to drink after work, and if there’s a regular activity at one of the bars that can facilitate meeting them, it might not be a bad idea to go and try to establish some connections in that community. This segues us nicely to…

3. Understand that moneyed people tend to have their own community

Generally, wealthy individuals know other wealthy individuals. If you develop a relationship with someone within that community, it means that even if that investor you ended up establishing a relationship with won’t invest, they may talk to a friend about it who might.

The reverse of this notion is also true. If you get a bad reputation in the Wealthy community then you’re likely to find it very hard to raise funds for your next film.

4. Understand that most people with money will have other investment options.

As stated above, film investment is highly volatile and inherently risky. If these investors took on every potential project that comes asking for their money, they would not be rich for very long. As such, you’re going to have lots of competition when it comes to raising funds for your film. This competition will not only come from other films, but also from stocks and bonds, other startups and small businesses, and even the notion that if they’re going to spend 100k they never get back, why not just buy a new Mercedes?

5. Find a not entirely monetary way to close the deal.

So to bring the last point home, you have to find other reasons that aren’t solely based on return on investment to get people to consider investing in your independent film. This can be the tax incentives, the moral argument to support culture, the fact that investing in a film is an inherently interesting thing to do, or a few other potential things. The blog below explores this in much more detail than I have the time or the word count to do here today.

Related: Why Don't Rich Tech People Invest in Film Part 5: Diversification and Soft Incentives

If you still need help financing your film, you should check out my free indiefilm business resource package. It’s got lots of tools and templates to to help you talk to distributors and investors, as well as a free-ebook so you can know what you need to know to wow them when you do. Additionally, you’ll get a monthly content digest to help you stay up to date on the ins and outs of the film industry, as well as be the first to know about new offerings and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media. Get it for free below.

7 Reasons Courting an Investor is Like Dating

Closing investment for your film is all about your relationship with your investor. It’s weirdly like dating. Here’s why.

There’s an old adage that Investing is like Dating. In fact, I’ve talked about the similarities both on meetings with investors, and dates with people who are qualified to be investors. So as something of a tongue-in-cheek yet still (Mostly) safe-for-work post, here are 7 ways courting an investor is like dating.

1. Your goal is to see how compatible you are with the other person.

Most of the time, if you want to get into bed with someone, you want to be compatible with them first. Getting money from an investor isn’t like a one-night stand. You don’t just get the check and then never hear from them again. Getting into bed with an investor is a long-term deal, so making sure you two work well together is simply a must. Otherwise, the break-up may not be pretty.

2. If you come off as Asking for too much the first time out, you probably won't get a second.

The first time you go out with an investor is kind of like that first coffee date. you’re both sizing each other up, and you want to see how you click. If you went on a first date trying to make out and take the partner back to your place, it’s probably not going to end well for you. Similarly, if you start asking an investor to whip out their checkbook on the first meeting, then you’re not likely to get a call back for a second.

In summation, the goal of your first date should always be to get a second. If you’re out with an investor, then the second meeting is the sole goal of the first meeting.

3. It Generally takes at least 3-5 meetings to jump into bed together.

As with dating, it generally takes 3-5 meetings to decide to get into bed together. Often, the longer it takes the more likely it is that the relationship will be fruitful down the line. At least to a point. If it takes more than 7 meetings to get a check, the investor (or your romantic partner) might just want to be friends.

4. Both Parties have something to gain, but generally speaking one has significantly more options than the other.

Just like women are generally more sought after than men in the dating scene, Investors are generally more sought after than entrepreneurs. This may sound crass, but the only pretty girl in the room is going to get a lot more offers than the 10 guys pursuing her. The ratio is similar for investors.

So sure, while everybody is looking for a mate, and every investor needs deal flow, generally one side has more options than the other. It’s important to remember that when attempting to court an investor.

5. They're Probably going to Google You.

Everybody does diligence in this day and age. If you didn’t think your date was going to check out your online presence, you should probably think again. Investors are going to look into your past history, and maybe even check your credit before they invest in you. Dates will do as much as they can on a similar level, but probably not check your credit.

Related: 5 Steps for Vetting Your Investors

6. If you jump into bed on the first date, you're in for a wild ride. a

One-night stands can be fun and all, but if you jump into bed with the wrong person right after meeting them it can be a real nightmare. (Or so I’ve been told…) If you don’t take the time to get to know somebody before you get into a serious relationship with the, you’re going to be in for a nasty surprise. All investment deals are serious relationships. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

7. When you seal the deal, you might be stuck with that person for YEARS.

If you take money from someone you’ll be dealing with them until all investors somehow exit the company. This can be many years. The Series A Investors at Twitter didn’t exit until their IPO Years later, and a film generally takes 3-5 years to pay back their investors, if they ever do.

If you do get into bed with an angel investor to finance your feature film or web series, they’re going to be a part of your business for a long time. It’s not just about finding independent film angel investors, it’s also about courting them and making sure you’ve found the right investor, not just the first investor who makes you an offer.

If you want some help with this courting process, my free resource package is a great place to start. It’s got a free e-book that might answer some questions your investor may have. It’s also got a deck template you can use in your first meeting. Get it for FREE below.

Check out related content using the tags below.

The Two Main types of Financial Projections for an IndieFilm

If you’re seeking investment for your movie, you need to know how much it will make back. Here are the 2 primary ways to do that.

As a key part of writing a business plan for independent film, a filmmaker must figure out how much the film is likely to make back. This involves developing or obtaining revenue projections.

There are generally two ways to do this, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The first way is to do a comparative analysis. This means taking similar films from the last 5 years and plugging them into a comparative model to generate revenue estimates. The second way is to get a letter of intent from a sales agent and get them to estimate what they could sell this for in various territories across the globe.

This blog will compare and contrast these two methods (Both of which I do regularly for clients) in an effort to help you better understand which way you want to go when writing the business plan for your independent film.

Would you Rather Watch/Listen to this than read it? Here’s a corresponding video on my YouTube Channel!

Comparative Analysis - Overview

A comparative analysis is when you comb IMDb Pro and The-Numbers.com to come up with a set number of comparable films to yours. These are films that have a similar genre, similar budgets, similar assets, are based on similar intellectual property, and are generally within the last 5 years. If you can match story elements that are a plus, but there are only so many films with the necessary data to compare.

When I do it, I compare 20 films, average their ROIs from theatrical, pull numbers from home video wherever I can (Usually the-numbers.com), and then run them through a model I’ve developed to come up with revenue estimates. Honestly, I don’t do a lot of this work. Most of the time I refer it to my friends at Nash Info Services since they run The-Numbers.com and the brand behind these estimates means a lot to potential investors.

I will do it when a client asks though, generally as a part of a larger business plan/packaging service plan.

Sales Agency Estimates - Overview

Sales Agency Estimates are when you get a letter of intent from a sales agent, and as part of that deal the sales agent prepares estimates on what they think they can sell the film for on a territory-by-territory basis. Generally, they work from what buyers they know they have in these territories, whether or not they buy content like this, and what they normally pay for content like yours.

These estimates are heavily dependent on the state of your package, who’s directing your film, and who’s slated to star in it. If you don’t have much of a package and a first-time director, then you’re not going to get very promising numbers.

Comparative Analysis - Benefits

Generally, anyone can get these estimates. Some people figure out the formula and do it themselves, others pay someone like me or Bruce Nash to do it for them. There’s either a not insubstantial fee involved or a lot of time involved in getting them. They’ll generally satisfy an investor, especially if Bruce does it.

Sales Agency Estimates - Benefit

The biggest benefit to a sales agency approach is that if they’re doing estimates for you, they’re probably going to distribute your film. Also, these estimates have the potential to be more accurate, because they’re based on non-public numbers on what buyers are paying in current market conditions. Finally, if a sales agent has given you an LOI, these estimates are generally free.

Comparative Analysis - Drawbacks

The first drawback is likely that they’re either very time intensive or somewhat costly to produce. Also, because VOD Sales data is kept under lock and key, it’s very difficult to estimate total revenue from VOD using this method. Given how important VOD is, that’s a somewhat substantial drawback.

Further, these estimates are greatly helped by the name value of who made them. Likely, if the filmmaker makes them themselves, then they’re not as viable as if someone like Bruce or Me does them. This is not only because we both have a track record in them, (Bruce much Moreso) but also because we’re mostly impartial third parties.

These revenue estimates can be very flawed if a filmmaker makes them because many filmmakers have a tendency to only pick winners, not the films that lost money. In business, we call this painting too blue a sky, as it makes everything look sunny with no chance of rain. In film, there’s always a substantial chance of rain.

Sales Agency Estimates - Drawbacks

The biggest drawback to these estimates is that not everyone can get these estimates. You have to have a relationship with the sales agency for them to consider giving them to you. Generally, you’ll need to have convinced them to give you an LOI first. That’s not always the case though.

If you have a producer’s rep, they can sometimes get you through the relationship barrier, but they’ll often charge for doing so when we’re talking about a film that’s still in development.

Also, Sales agencies can sometimes inflate their numbers to keep filmmakers happy and convince them to sign. This does not look good to investors if that money never comes in

Conclusion

Overall, which method you use to estimate revenue depends entirely on what situation you find yourself in. If you have the ability to get the sales agency estimates, they can be VERY strong, if you don’t, the comparative estimates are reliable enough to do what you need them to do. That being said, I wouldn’t advise taking a comparative analysis to a sales agency.