The Basics of Financing your Independent Film with Tax Incentives

Making a profit on an indie film is HARD. If you can get your film subsidized by a tzx incentive your job is a lot easier. Here are the basics to get you started on that path.

Most filmmakers simply chase equity in order to finance their films. However, most investors don’t want to shoulder the financial risk involved in a film alone. That’s where tax incentives for independent film can come in and help to close the gap. But proper use of tax incentives for independent film financing is somewhat complicated. Here’s a primer to get you started.

Cities, States, Regions, and countries can have tax incentives

First of all, it’s important to understand that most forms of government can issue a tax incentive. In the US, the biggest and best incentives generally (but not always) come from states, however many cities, counties, and regions may supplement those incentives with smaller Internationally, many countries also provide some level of subsidy.

Europe Tends to provide better tax incentives than the US.

From the standpoint of the federal government, most European countries are much better about independent film subsidies than the US. Most of the time, these incentives take the form of co-production funding, but it’s relatively common for film commissions to provide grants to help promote the arts among their citizens.

This is particularly notable given that citizens of EU Member States can strategically stack incentives in a way that the majority of your film is financed via government subsidies. If, like me, you are based out of the United States, that’s just not possible due to the structure of most tax incentives.

There’s normally a minimum spend.

Especially in the US, there’s generally a fairly hefty minimum spend to qualify for a tax incentive. In some states that spending can start around 1 million dollars for out-of-state productions. Some states offer a lower cap for productions helmed by residents of the state.

There’s generally a minimum percentage of the total film budget needing to be shot there.

Most of the time you’ll only be eligible for a tax incentive if you shoot a certain percentage of your film or spend a certain percentage of your budget in a given territory. These can vary widely from territory to territory so look at the first place.

It’s normally not cash upfront

Unless you’re getting a grant from whatever film commission you’re shooting in, you’re probably just going to get a piece of paper that will state that you will be audited after the production and paid out according to the results of the audit. There are generally a few different ways that a tax incentive can be structured, but we’ll touch on those next week.

You need to plan for monetizing it.

In general, you’ll either end up selling the tax incentive for a percentage of its total value to a company with a high tax liability in your state, or you’ll have to take out a loan against your tax incentive in order to get the money you need to make the film. Both of these incur some level of cost which is different depending on which state you’re shooting in.

For example, Georgia and Nevada both have transferrable tax credits. Due to the large amount of productions going on in Georgia on a pretty much constant basis, the transferrable tax credit often monetizes at around 60% of face value. Nevada on the other hand has relatively few productions and many casinos that have very high tax burdens. As a result, the tax incentive in Nevada tends to monetize at around 90%. That said, there is presumably a more tested, experienced crew in Georgia than in certain parts of Nevada, of course, the film commission will tell you differently.

Not everything is covered

Not every expense for your film is covered. Exactly what is covered can vary widely from state to state, but in general only expenses that directly benefit the economy of the state are covered. There are often exceptions. One common exception is some mechanism to allow recognizable name talent to either be included in a covered expenditure or at least exempted from minimum thresholds of state expenditures.

Most of the time, high pay for above-the-line positions such as out-of-state recognizable name talent or directors are not covered covered by tax incentives. However, there are a few states that allow it. I talk a lot about it in this Movie Moolah Podcast with Jesus Sifuentes, linked below.

Related Podcast: MMP:003 Non-Traditional Investors & Maximizing Tax Incentives W/ Jesus Sifuentes

Not every program is adequately funded

Many film programs have a “cap” If that cap is too low, the money can be gone before the demand for the money is. Some states have the opposite problem.

Communicating with the film commission pays dividends long term

In general, the film commissions I’ve talked to are extremely friendly and easy to talk to. However, many times these commissions lose touch with the filmmakers they’re supporting shortly after they shoot. This isn’t necessarily a good thing, as most film commissions have significant reach into the greater film community and other aspects of local government. If you make sure they stay up to date as to what’s going on with your project you may find yourself getting help from unexpected places.

Also, if this is all a bit complicated, you should check out this new mentorship program I’ve started to help self-motivated filmmakers get additional resources as well as get their questions answered by someone working in the field. It’s more affordable than you may think. Check out my services page for more information.

If you’re not there yet, grab my free film Business Resource package. It’s got a lot of goodies ranging from a free e-book, free white paper, an investment deck template, and more. Grab it at the button below.

Finally, If you liked this content, please share it.

Click the Tags below for more, related content!

Filmmakers Glossary of Film Business Terminology.

I’m not a lawyer, but I know contracts can be dense, confusing, and full of highly specific terms of art. With that in mind, here’s a glossary of Art. Here’s a glossary to help you out.

A colleague of mine asked me if I had a glossary on film financing terms in the same way I wrote one for film distribution (which you can check out here.) Since I didn’t have one, I thought I’d write one. After I wrote it, it was too long for a single post, so now it’s two. This one is on general terms, next week we’ll talk about film investment terms. As part of the website port, I’m re-titling the first part to a general film business glossary of terms, to lower confusion on sharing it. It’s got the same terms and the same URL, just a different title.

Capital

While many types exist, it most commonly refers to money.

Financing

Financing is the act of providing funds to grow or create a business or particular part of a business. Financing is more commonly used when referring to for-profit enterprises, although it can be used in both for profit and non-profit enterprises.

Funding

Funding is money provided to a business or non-profit for a particular purpose. While both for-profit and non-profit organizations can use the term, it’s more commonly used in non-profit media that the term financing is.

Revenue

Money that comes into an organization from providing shrives or selling/licensing goods. Money from Distribution is revenue, whereas money from investors is financing, and donors tend to provide funding more than financing, although both terms could apply.

Equity

A percentage ownership in a company, project, or asset. While it’s generally best to make sure all equity investors are paid back, so long as you’ve acted truthfully and fulfilled all your obligations it’s generally not something that you will forfeit your house over. Stocks are the most common form of equity, although films tend not to be able to issue stocks for complicated regulatory reasons and the fact that films are generally considered a high-risk investment.

Donation

Money that is given in support of an organization, project, or cause without the expectation of repayment or an ownership stake in the organization. Perks or gifts may be an obligation of the arrangement.

Debt

A loan that must be paid back. Generally with interest.

Deferral

A payment put off to the future. Deferrals generally have a trigger as to when the payment will be due.

“Soft Money"

In General, this refers to money you don’t have to pay back, or sometimes money paid back by design. In the world of independent film, it’s most commonly used for donations and deferrals, tax incentives, and occasionally product placement. It can have other meanings depending on the context though.

Investor

Someone who has provided funding to your company, generally in the form of liquid capital (or money.)

Stakeholder

Someone with a significant stake in the outcome of an organization or project. These can be investors, distributors, recognizable name talent, or high-level crew.

Donor

Someone who has donated to your cause, project, or organization.

Patron

Similar to donors, and can refer to high-level donors or financial backers on the website Patreon. For examples of patrons, see below. you can be a patron for me and support the creation of content just like this by clicking below.

Non-Profit Organizations (NPO)

An organization dedicated to providing a good or service to a particular cause without the intent to profit from their actions, in the same way, a small business or corporation would. This designation often comes with significant tax benefits in the United States.

501c3

The most common type of non-profit entity file is to take advantage of non-profit tax exempt status in the US.

Non-Government Organization (NGO)

Similar to a non-profit, generally larger in scope. Also, something of an antiquated term.

Foundation

An organization providing funding to causes, organizations and projects without a promise of repayment or ownership. Generally, these organizations will only provide funding to non profit organizations. Exceptions exist.

Grantor

An organization that funds other organizations and projects in the form of grants. Generally, these organizations are also foundations, but not necessarily.

Fiscal Sponsorship

A process through which a for-profit organization can fundraise with the same tax-exempt status as a 501c3. In broad strokes, an accredited 501c3 takes in money on behalf of a for-profit company and then pays that money out less a fee. Not all 501c3 organizations can act as a fiscal sponsor.

Investment

Capital that has been or will be contributed to an organization in exchange for an equity stake, although it can also be structured as debt or promissory note.

Investment Deck (Often simply “Deck”)

A document providing a snapshot of the business of your project. I recommend a 12-slide version, which can be found outlined in this blog or made from a template in the resources section of my site, linked below.

Related: Free Film Business Resource Package

Look Book

A creative snapshot of your project with a bit of business in it as well. NOT THE SAME AS A DECK. There isn’t as much structure to this. Check out the blog on that one below.

Related: How to make a look book

Audience Analysis

One of 3 generally expected ways to project revenue for a film. This one is based around understanding the spending power of your audience and creating a market share analysis based on that. I don’t yet have a blog on this one, but I will be dropping two videos about it later this month on my youtube channel. Subscribe so you don’t miss them.

Competitive Analysis

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. This method involves taking 20 films of a similar genre, attachments, and Intellectual property status and doing a lot of math to get the estimates you need.

Sales Agency Estimates

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. These are high and low estimates given to you by a sales agent. They are often inflated.

Related: How to project Revenue for your Independent Film

Calendar Year

12 months beginning January 1 and ending December 31. What we generally think of as, you know, a year.

Fiscal year

The year observed by businesses. While each organization can specify its fiscal year, the term generally means October 1 to September 30 as that’s what many government organizations and large banks use. Many educational institutions tie their fiscal year to the school year, and most small businesses have their fiscal year match the calendar year as it’s easier to keep up with on limited staff.

Film Distribution

The act of making a film available to the end user in a given territory or platform.

International Sales

The act of selling a film to distributors around the world.

Related: What's the difference between a sales agent and distributor?

Bonus! Some common general use Acronyms

YOY

Year over Year. Commonly used in metrics for tracking marketing engagement or financial performance on a year-to-year basis.

YTD

Year to Date. Commonly used in conjunction with Year over year metrics or to measure other things like revenue or profit/loss metrics.

MTD

Month to Date. Commonly used when comparing monthly revenue to measure sales performance. Due to the standard reporting cycles for distributors, you probably won’t see this much unless you self-distribute.

OOO

Out of Office. It generally means the person can’t currently be reached.

EOD

End of Day. Refers to the close of business that day, and generally means 5 PM on that particular day for whatever the time zone of the person using the term is working in.

Thanks for reading this! Please share it with your friends. If you want more content on film financing, packaging, marketing, distribution, entrepreneurialism, and all facets of the film industry, sign up for my mailing list! Not only will you get monthly content digests segmented by topic, but you’ll get a package of other resources to take you film from script to screen. Those resources include a free ebook, whitepaper, investment deck template, and more!

Check the tags below for more related content!

How to Raise Development Funds for your Feature Film.

If you want to make a movie, you need to raise money. In order to raise any significant capital, you’ll need a package, and that cost money. Here’s where you raise the first money in.

Pretty much every filmmaker wants to find money to make their movie. Unfortunately, many don’t quite realize that in order to raise the kind of money you need to make anything above a micro-budget movie, you’ll generally need a lot already in place. It’s something of a catch-22. Investors need name talent to market the film, and distribution to make it available. Distributors need name talent and a tested team to give any meaningful commitments, and name taken need to know they’ll be paid. There are ways around all of this, but generally, they require money upfront. This blog is about how you raise it.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a magic bullet on any level of film funding. The best I can do is offer you tools and tactics to use to increase your chances of success. You will probably need more than one of these tools to get the job done.

Don't want to read? Check out the video on this topic below

Crowdfunding

Let’s get this one out of the way fast. Crowdfunding CAN be great for filmmakers not only as a way to raise partial funding, but also to engage yourself with your audience and provide market validation for both investors and distributors/sales agents. That said, it’s not without its drawbacks. Using crowdfunding as an early-stage race tool can cause your donors to question whether or not you’ll be able to get the whole film done. If you can’t, it can lead to problems. (Extra special shoutout to my patrons here, since we’re talking about crowdfunding.)

Friends and Family

I know, I know. This is the oldest piece of advice in the book. But, there’s a reason it’s still around. Your friends and family are (hopefully) among the people who are most likely to back and support you in this endeavor. If they’re like mine were when I was starting out, while they may be willing to help and actively want you to succeed, they’ll still need some proof it’s possible. However, the proof they’re like to need will probably be something easier to get than an investor would need. These

Equity

But Ben, didn’t you just say that you need more in place to get an investor? Yes and no. In order to raise a large round, you’ll need a lot in place, but if you’re only focusing on a smaller round you can get by with less. It is important to properly structure this investment though. You’ll either need to offer a more substantial stake in the company for the bigger risk taken for investing earlier, or you’ll need to do some other investment vehicle like Convertible debt.

Even at this stage, if you want to raise money from investors you’re going to need to create an independent film investment deck. You can learn more about it in this blog, or you can grab a template for free in my film business resource package in the button below.

Grants

Grants are great in that they don’t require you to pay back the money so long as you only use it for its intended purpose. They’re not so great in that they generally take a long time to be approved for the money, and you’re generally facing significant competition particularly for development stage grants.

Soft Costs and Deferrals

This essentially means calling in every favor you have to make sure that you have the best chance possible to succeed in developing a package for your film. This isn’t going to carry you the whole way though. Most people who do this for a living don’t work purely on a deferral or commission basis. I’m including myself in this, although I do defer a large portion of my fees and take on as much as I can on commission.

That said, while the higher-level connectors, Producers, Executive Producers, and the like are generally unwilling to work on a purely deferral or commission basis, the friends you need to make a great crowdfunding video, concept trailer, or something similar might not be. Getting their buy-in might help you make it to the next level.

Skin in the Game

Finally, we come down to the ever-present fallback of funding the development round yourself. This is generally the fasted way to complete the round, but it has the obvious drawback of needing deep enough pockets to just shell out and pay the money you need to get it done.

I know all of this is really hard to grasp, and quite frankly it’s a lot. While I do consult on this sort of stuff, I’m not cheap. (with good reason.) I try to make a lot of information available through my site, but there are times that you just kind of need someone to answer your questions and re-orient you. As such, I’ve decided to start a special mentorship group.

This special training group gets you access to additional content, an exclusive discussion group, and most importantly weekly group video calls where I’ll answer your questions personally, and occasionally bring on people who would also be of benefit to the group’s needs. Click the button below to go to a form and express interest in this group. Spots are limited.

Also, don’t forget about the Free indiefilm business resource package to get your free Investment deck template, e-book, white-paper, and more. .

Thanks so much for reading. Please share it! Also click the buttons below for more free content.

How Did Film Distribution Get So Broken?

Filmmakers know the system sales agents use to exploit their content is well, exploitative. The issue runs deeper that dishonesty. Here’s an exploration.

It’s no secret that many (if not most) filmmakers think film distribution is broken. While there are many reasons for it, part of it is due to the rapid change in the amount of money flowing to distributors, and what constituted effective marketing. What works for marketing films now isn't what worked in the past, and the systems distributors built themselves around have fallen apart. Here's an elaboration.

First, some history.

Independent Film Distribution used to be primarily a game of access. By controlling the access and becoming a gatekeeper, it was easy to make buckets of cash. If you had a VHS printer and access to a warehouse facility that could help you ship to major retail outlets you could make literal millions off of a crappy horror film.

In those days it was also significantly harder and significantly more expensive to make a film, as you’d need to buy 16mm or 35mm film, get it duplicated, cut it by hand using a viola, and then reassemble it and have prints made. This was a very expensive process, so the number of independent films that were made was much smaller than it is today.

Then DVD came along, and around the same time some of the early films from the silent era that actually had followings entered the public domain. As such, a good amount of companies started printing those to acquire enough capital to buy libraries and eventually build themselves into major studios. Sure, DVD widened the gate a bit, but it also expanded the market so everyone was happy.

Around this time, Non-Linear Editors and surprisingly viable digital and tape cameras were coming into prominence. As a result, it became much more possible to make an independent film than it was before. Of course, at that time it was still beyond the reach of most people, and since the average amount of content being made went up, the demand was growing enough that there still wasn’t a massive issue with oversaturation.

A similar expansion was expected with Blu-Ray, but at around the same time, alternative services like iTunes were starting to become viable as broadband internet was becoming commonplace. As such, the demand for physical media started to dwindle, and as a result, the revenue being made dropped.

At the same time, Full HD cameras were now very affordable, and some even rivaled 35mm film. So the amount of money being made in the industry went down, and more films were being made than ever before.

Shortly after that, the ability to disintermediate and cut out the gatekeepers came to be. As such, the market became flooded with often low-quality films that the challenge was no longer getting your film out there, it was now getting your film noticed. That’s where we are now, and nobody has fully been able to solve that problem yet.

Here’s a summary of how we got there, and how the process of distribution has changed.

Access USED to be enough

It used to be that access was all you needed. Once you had that, you could make an insane amount of money selling other people’s content.

Sell it on the box art

The box art being caught was the most important thing. Stores didn’t let you return movies because you didn’t like them, and other than your own limited circle of friends consumers didn’t have a lot of power to let people know about bad movies, or bad products in general.

Sell it on the trailer

Even if it was bad, nothing would come of it. Once you had their money, that was all you needed. The idea of making your money in the first weekend before bad word of mouth got around was much more viable as people couldn’t just tweet it out or rant about it on Facebook or YouTube.

Let’s contrast that with how things work Now:

Access is easy

Anyone with a few thousand dollars can put their film up on most Transactional platforms on the internet. You can also put it on Amazon or Vimeo yourself for free. There are very few in terms of quality controls.

the Poster/keyart is still important, but reviews are more important.

Sure, people still get their eyes caught by a poster. But the reviews matter significantly more in terms of getting them to a purchase decision. The poster may catch their eye, but the meta score from users on whatever platform you’re watching the film on is important.

The trailer might still be the deciding factor

Generally, after people see the poster, they’ll read the synopsis, and then they’ll either watch the trailer or read the reviews. If they watch the trailer, they may have more leniency on reviews.

Also, if the trailer is really good, it can get a bit of viral spread.

If it’s bad, it will become known.

Thanks to social media, if the film is bad it’s not hard to let people know about it. If the film is mismarketed, people will know. As such, authentic marketing to the film is extremely important.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this blog, you’ll probably like the stuff you get on my mailing list. That includes a film marketing & distribution resource packet, as well as monthly digests of blogs just like this one. Or, if you’re researching whether or not you want to self-distribute your independent film, you might want to submit it. I have hybrid models for distribution that help filmmakers build their brands, and get the right amount of visibility for their films so they can rise above the white noise. Check out the buttons below, and see you next week!

Check the tags below for free related content!

When and Where to use Each Indiefilm Investment Document

Most Sales agents don’t want your business plan, and a bank doesn’t want your lookbook. Here’s what stakeholders do want, and when.

There are 3 different documents you would need to approach an investor about your independent film. I’ve written guides on this blog to show you how to write each and every one of them. Those three documents are a Look Book (Guide linked here.) a Deck (Guide Linked Here) and a business plan. (Part 1/7 here) But while I’ve Written about HOW to create all of these documents, I’ve held back WHY you write them, WHO needs them, and WHEN to use them. So this blog will tell you WHO needs WHAT document WHEN and HOW they’re going to use it.

As with some other blogs, I’ll be using the term stakeholder to refer to anyone you may share documents with, be they an investor, studio head, sales agent, Producer of Marketing and Distribution (PMD) or Distributor.

What are these documents and WHY do you share them?

So first, let’s start with what each document is, just in case you haven’t read the other blogs (which you still should)

A Look book for an independent film is an introductory document, that’s very pretty and engaging and gives an idea of the creative vision of the film. The purpose is to get potential stakeholders interested enough in the project to request either a meeting or a deck. The goal in showing them this document is to get them to start to see the film in their head and get them to become interested in the project on an emotional level.

Related: Check out this blog for what goes into a lookbook

A Deck is a snapshot of the business side of your film. The goal is to send them something that they can review quickly to get an idea of how this project will go to market and how it will make money so that they get an idea of how they’ll get their money back.

Related: The 12 Slides you need in your indie film investment Deck

A business plan is a detailed 18-24 page document broken into 7 sections that will give potential investors not only an idea of your investment but of the industry as a whole. In a sense, it’s equal parts education and persuasion, especially for investors new to the film industry. The goal is to give the prospective stakeholder a deeper understanding of the film and media industry, and a very thorough understanding of your project and the potential for investing in it.

Related: How to Write an Indiefilm Business Plan (1/7 - Executive Summary)

WHO needs these documents and HOW they’ll use it

Different stakeholders need these documents at different times.

Look Books should be sent to any potential stakeholder, including investors, studio heads, sales agents, distributors, producer’s reps, Executive Producers, and more. It’s a creative document that gives a good idea of the product at the early stage. It helps people gauge interest in your project

Decks are primarily used by Investors, Executive Producers, PMDs, and potentially Sales Agents. Distributors and Studio Heads are less likely to need a deck since they know the business better than you do. At least most of the time.

Business plans are primarily needed by angel investors new to the film industry and Angel Investment Syndicates to use as the backbone for the Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) The First and last sections of the business plan (The Executive Summary and Pro-Forma Financial Statements) may be more widely used, often at the same general place as the deck, or only shortly after.

WHEN do they need these documents?

Look books come early on. It’s generally the first thing they’ll ask for when considering your project.

Decks come shortly after the lookbook. Sometimes in an initial meeting, or sometimes directly after that first meeting.

Looking at a business plan is generally very deep in the process of talking to a potential stakeholder, it’s almost always after at least 2-3 meetings and a thorough review of the deck.

If this was useful, you should definitely grab my free film business resource packet. It’s got templates for some of these documents, a free e-book, a whitepaper that will help you write these documents, as well as monthly blog digests segmented by topics about the film business so you can sound informed when you talk to investors. Click the button below to grab it right now.

Check out the tags for related content.

The 12 Slides You Need in Your IndieFilm Investment Deck - WITH TEMPLATE!

Generally, when you have your first serious meeting with an investor they’ll ask to see your deck. Here’s what they want.

Pitching to independent investors is a much different formula than we’re generally taught in Film Schools. The formula we’re taught in Film School is generally built around a studio pitch. A studio does a lot more than give money to a project. They have huge marketing, PR, legal, and distribution teams that they use to monetize any films they finance. As such it’s not the filmmaker’s job to pitch their projects on anything except story when working within that system.

Would you rather Watch a video than read a blog? I've got you covered in the video from my Youtube Channel.

Filmmakers must take a different approach when talking to independent film investors. Generally, angel investors are only looking to finance projects, they don’t have resources to help market and distribute the film. While Film is a highly speculative and inherently risky investment, and most film investors don’t invest in film solely for the ROI, they need to know you have a path to get their money back to them.

There’s a certain formula for creating a successful slideshow for investors. These presentations (Generally referred to as “Decks” in Silicon Valley) have been honed to tell the story of your company. Investors are used to seeing this format when deciding whether or not to invest in your project. It’s pretty easy to find samples of this formula for regular companies on SlideShare, but since the film industry is so specialized there must be some modifications made to the formula in order to make a good Deck to pitch your film to an investor. Below is a breakdown of what should go into a Filmmaking deck, or you can just grab the template in the resource pack.

SLIDE 0 – Project Name/Artwork.

In a standard company pitch, the first thing that appears is the name of the company and the logo. For a film or media project, instead use the name of the project, the name of your production company, and the one sheet for your project.

SLIDE 1 – Project Overview

Generally, this would be where an entrepreneur would put an overview of his or her company, what it does, and what its mission is. For a film or media project, put the logline of your project, as well as the genre and a basic overview of the story.

SLIDE 2 – Why Does this Project Need to be Made?

In a standard company pitch, slide 2 and 3 would be the problem that the company seeks to solve, and the solution it offers. Since Films are generally made more as entertainment, they don’t always have a problem that they’re fixing. So instead, focus on why this project should be made.

Some approaches you could take on this would be that there’s not enough family-friendly media being made, Women and minorities are vastly underrepresented in media, young LGBT kids need a role model, or that whatever niche you’re targeting doesn’t have enough entertainment. Figure out WHY your story needs to be told, and it can’t just be that you’re an artist and it’s in your soul.

SLIDE 3 – Why Your Project is the One to tell That Story

In the standard company deck, this would generally be the solution that your company offers. For film, focus on why you and your team are the ones to tell the story you established in slides 1 and 2. Don’t go too deep into the team, you’ll cover that later.

SLIDE 4 – Opportunity

This slide is where an entrepreneur or filmmaker focusus on the size of the market and how they plan to access it. Focus on any niche communities you can target, and the genre your film is in generally performs internationally.

SLIDE 5 – Unique Competitive Advantage

Your Unique competitive advantage will remain mostly the same as it would in a pitch for any sort of company. You need to emphasize why your film should be the one they invest in. Do you have a large following in the niche audiences you’re targeting? Do you have some unique insight into the subject matter that no one has heard before? Is there something unique about your background that makes you the ideal person to tell this story.

Focus on why your film or media project will stand apart from the competitors and has the best chance to make a profit. In short, How will you stand out from the pack when others don’t?

SLIDE 6 – Marketing Strategy

Long time silicon valley strategist Sheridan Tatsuno likens market research to setting up a target, and marketing to shooting the arrow at it. You’ve set up the target in slides 4 and 5, now it’s time to show how you’re going to shoot the arrow and make a bullseye. How will you utilize social media? Which platforms will you use? Are you already a part of the communities of your target market?

SLIDE 7 – Distribution Strategy

Generally, this would be your Go-To-Market strategy. In the film industry, this essentially means your distribution strategy. What rights will you be handling yourself, and what rights will you be handing to a distributor? What platforms will you use? How will you handle US Sales? Are you planning on attaching an international sales agent? How will you go about doing that if you haven’t already?

SLIDE 8 – Competitive Analysis

Show other films in a similar genre that have done well. Remember, this isn’t your business plan, so only show about 3 if you’re showing individual projects, not the 20 you should research. If you’ve already done your full competitive analysis, show one or two profitable representative samples and then the aggregate on all of the 10-20 films you researched. The charts and tables are good here.

You only want to use content from the last 3-5 years. Content older than that doesn’t realistically represent the current marketplace. This is something that even professionals who estimate ROIs don’t always follow. It’s always a red flag for investors when your examples are too old,

SLIDE 9 – Financials

Generally, you’ll need a few of the major line items from your top sheet budget. A good bet would be your above-the-line, pre-production, principal photography, post-production, and marketing and distribution (or P&A) costs. Due to union caps, it can often be beneficial to raise your marketing and distribution budget at a later date. Projected ROI will also go on this slide.

SLIDE 10 – Current Status

This should be fairly self-explanatory, but here are a few questions to ask yourself. What have you accomplished so far? Do you have any talent attached? Are you talking with Sales Agents? Where is the script in development? Are there any notable crew on board?

SLIDE 11 – Team

Focus on why you and your team are uniquely qualified to not only bring this film to completion but deliver a quality product that can give an excellent ROI to all involved. Has your leadership team won awards at festivals? Have projects they’ve been on done impressive things?

SLIDE 12 – Summary/Thank You

For the final slide, put the three most important and/or marketable things about your project into a single slide. Investors get approached with a lot of opportunities and their brains can get cluttered. If an investor walks away knowing only these three things about your project, what do you want them to be?

Most importantly, thank them for their time and consideration, and make sure there’s an easy-to-find way to contact you ON YOUR DECK. Ideally on the first and last page. We’ll often send out decks when we send out the executive summary, so make yourself easy to contact if they’re interested.

Also, I alluded to this at the top of the article in the image caption, but this post did indeed originally appear on ProducerFoundry.com. But, this isn't just a port. I also set up a FREE template in both Keynote and Powerpoint in my resources packet. Grab that with the buttons below.

How To Write a Business Plan for an Independent Film - 3/7 Project(s)

Filmmakers don’t tend to plan to fail, but they often fail to plan. Here’s how to write the project section of an independent film business plan.

Next up in my 7 part series on writing a business plan for independent film, we’ll be taking a deeper look at the project(s) section of the plan. The projects section of the plan is the most creative section, as it talks about the creative work that you’re seeking to finance. That being said, it breaks those creative elements into their basic business points. This section should be no more than a page if you have one project, and no more than 2 pages if you’re looking at a slate.

GENRE

Genre is a huge part of marketing any film. It essentially categorizes your film into what interest groups you’ll be marketing. This subsection should focus on the genre of your film, as well as who you expect the film to appeal to.

For more information on the concept of Genre in Film as it pertains to distribution, check out this blog.

RELATED: WHY GENRE IS VITAL TO INDIEFILM MARKETING & DISTRIBUTION

PLOT SYNOPSIS

This is as it sounds. It’s a one-paragraph synopsis of your film. When you’re writing it, keep in mind that you’re not telling your story, so much as selling it. Make it exciting. Make it something that the person reading the plan simply will not be able to ignore.

BUDGET

This one should also be self-explanatory, list the total budget of your film. It would make sense to break it into the following categories. Above the Line, Development, Pre-Production, Principle photography, post-production, and producer’s contribution to marketing and distribution.

The last part is to acknowledge that while the distributor will be contributing a large amount to the marketing and distribution costs of the film, it will not be the sole contribution, and you as the filmmaker will likely have to contribute some amount of time and/or money to make sure your film is sold well.

RATING

This section talks about your expected rating. Say what you expect to get, what themes you think will cause the film to get that rating, and how that will help you sell the film to the primary demographic listed above.

MARKETABLE ATTACHMENTS

Did you get Tom Cruise for your movie? What about Joseph Gordon Levitt? Or maybe Brian De Palma came on to direct. If you have anyone like this (or even someone with far less impressive credits) make sure you list that you’ve got them. If you’re in talks with their people, list it here too.

Related: 5 Reasons you Still need Name Talent in your film

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY STATUS

Finally, you’ll need to list the intellectual property status of your film. By this, I simply mean is the concept original? Is it based on anything? Did you acquire the rights to whatever it’s based on? If you optioned rights, when does the option expire? If you optioned rights, who is the original owner of the rights?

Writing a business plan that can actually raise funding is a lot more than just using a template. If you want a leg up you should check out my free resource pack which includes a deck template, a free e-book, digests of relevant industry-related content, delivered to your inbox once a month, and notifications of special events and other announcements tailored to the needs of the filmmakers I work with.

You should know that I’ve written a few dozen business plans for filmmakers, some of which have raised significant funding. If you want to talk about it check out our services page.

Thanks so much for reading! You can find the other completed sections of this 7-part series below.

Executive Summary

The Company

The Projects (This Post)

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

Check the tags below for related content

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 2/7 Company Section

One of many things you’ll probably need to finance an independent film is a business plan. Here’s an outline of one of the sections you’ll need to write.

Last time we went over the basics of writing an independent film executive summary. This time, we’re diving into the first section of a business plan. By this I mean the company section. If you want an angel investor to give you money, they’re going to need to understand your company. There are some legal reasons for this, but most of it is about understanding the people that they’re considering investing in.

The company section generally consists of the following sub-sections. This section only covers the company making the film, not the media projects themselves. Those will be explored in section III - The Projects.

FORM OF BUSINESS OWNERSHIP

This is the legal structure you’ve chosen to form your company as. If you have yet to form a company, you can tell an investor what the LLC will be formed as once their money comes in. I’ve written a much longer examination of this previously, which I’ve linked to below. Also, I’m Not a Lawyer, that’s not legal advice, don’t @ me.

Related: The Legal Structure of your Production Company

THE COMPANY

This subsection talks a bit about your production company. You can talk about how long you’ve been in business, what you’ve done in the past, and how you came together if it makes sense to do so. Avoid mentioning academia if at all possible, unless you went to somewhere like USC, UCLA, NYU, or an Ivy League School. Try to make sure this section only takes up 2-3 lines on the page.

BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY

This is what you stand for as a company. What’s your vision? What content do you want to make over the long term? Why should an investor back you instead of one of the other projects that someone else solicited?

Your film probably can’t compete with the potential return of a tech company. I’ve explored that in detail over the 7 part blog series linked below.

Additionally, you might want to check out Primal Branding by Patrick Hanlon it’s a great book to help you better understand how to write a compelling company ethos. I use it with clients as it frames it exceptionally well for creative people. That is an affiliate link.

Related: Why don’t rich Tech people invest in film?

Since you can’t compete on the merits of your potential revenue alone, you need to show them other reasons that it would behoove them to invest in your project. See the link below for more information.

Related: Diversification and Soft Incentives

PRODUCTION TEAM

These are the key team members that will make your film happen. List the lead producer first, the director second, the Executive Producer second, and the remaining producers after that. Directors of photography and composers tend to not add a lot of value in this section, but if you’ve got one with some impressive credits behind them, it might make sense to add the.

Generally, if you have someone on your team with some really impressive credits, it might make more sense to list them ahead of the order I listed above.

Essential Reference Books for Indiefilm Business Planning

PRODUCT

This should talk a little about the films you’re going to make, and the films you’ve made in the past.

OPERATIONS

This is a calendar of operations with key milestones that you intend to hit during the production of the film. These would be things like:

Financing Completed

Preproduction Begins

First Day of Principle Photography

Completion of principal Photography

Start of post-production

You’ll also want to include when you intend to finish post-production, as well as when you intend to start distribution, but that should be less specific than the items listed above. For the non-bullied items, I would say that you should just give a quarter of when you expect to have them happen, whereas the bullets should be a month or a date.

CURRENT EVENTS

The Current events are as they sound, a list of the exciting events going on with your film and with your company. This could be securing a letter of intent from an actor, director, or distributor, completing the script, or raising some portion of the financing.

Assisting filmmakers in writing business plans is a decent part of the consulting arm of my business. The free e-book, blog digests, and templates in my resource package can give you a big leg up. That said, If this all feels like a bit much to do on your own you might want to check out my services page. Links for both are in the buttons below.

Thanks so much for reading! You can find the other completed sections of this 7 part series below

Executive Summary

The Company (This One)

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-forma Financial Statements.

Check the tags for more related content.

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 1/7 Executive Summary

If you want to raise money from an investor, you have to do your homework. That includes making a business plan. A business plan starts with an executive summary.

One of my more popular services for filmmakers is Independent Film Business Plan Writing. So I decided to do a series outlining the basics of writing an independent film business plan to talk about what I do and give you an idea of how you can get started with it yourself.

Before we really dive in it’s worth noting that what will really sell an investor on your project is you. You need to develop a relationship with them and build enough trust that they’ll be willing to take a risk with you. A business plan shows you’ve done your homework, but in the end, the close will be around you as a filmmaker, producer, and entrepreneur.

The first Section of the independent film business plan is always the Executive Summary, and it’s the most important that you get right. So how do you get it right? Read this blog for the basics.

Write this section LAST

This section may be the first section in your independent film business plan, but it’s the last section you should write. Once you’ve written the other sections of this plan, the executive summary will be a breeze. The only thing that might be a challenge is keeping the word count sparse enough that you keep it to a single page.

If you have an investor that only wants an executive summary, then you can write it first. But you’ll also need to generate your pro forma financial statements for your film, and project revenue and generally have a good idea of what’s going to go into the film’s business plan in order to write it. I would definitely write it after making the first version of your Deck, and rewrite it after you finish the rest of the business plan.

Keep it Concise

As the name would imply, the Executive Summary is the Summary of an entire business plan. It takes the other 5 sections of the film’s business plan and summarizes them into a single page. It’s possible that you could do a single double-sided page, but generally, for a film you shouldn’t need to.

A general rule here is to leave your reader wanting more, as if they don’t have questions they’re less likely to reach out again, which gives you less of a chance to build a relationship with them.

Here’s a brief summary of what you’ll cover in your executive summary.

Project

As the title implies, this section goes over the basics of your project. it goes over the major attachments, a synopsis, the budget, as well as the genre of the film. You’ll have about a paragraph or two to get that all across, so you’ll have to be quite concise.

Company/Team

This section is a brief description of the values of your production company. Generally, you’ll keep it to your mission statement, and maybe a bit about your key members in the summary.

Marketing/Distribution

In a standard prospectus, this would be the go-to-market strategy. For a film, this means your marketing and distribution sections. For the executive summary, list your target demographics, whether you have a distributor, plan to get one, or plan on self-distributing. Also, include if you plan on raising additional money to assist in distribution.

SWOT Analysis/Risk Management

SWOT is an acronym standing for Strengths Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. For the executive summary, this section should include a statement that outlines how investing in film is incredibly risky, due to a myriad of factors that practically render your projections null and void. Advise potential investors to should always consult a lawyer before investing in your film. Cover your ass. I’ve done a 2*2 table with these for plans in the past, and it works reasonably well. Speaking of covering one’s posterior, you should have a lawyer draft a risk statement for you. Also, I am not one of those, just your friendly neighborhood entrepreneur. #NotALawyer #SideRant

Financials

Finally, we come to the part of the plan that the investors really want to see. How much is this going to cost, and what’s a reasonable estimate on what it can return? There are two ways of projecting this, outlined in the blog below.

Related: The Two Ways to Project Revenue for an independent film.

In addition to your expected ROI, you’ll want to include when you expect to break even and mention that pro forma financial statements are at the end of this plan included behind the actual financial section.

Pro Forma Financial Statements.

If you’re sending out your executive summary as a document unto itself, you will strongly want to consider including the pro forma financial statements. For Reference, those documents are a top sheet budget, a revenue top sheet, a waterfall to the company/expected income breakdown, an internal company waterfall/capitalization table, a cashflow statement/breakeven analysis, and a document citing your research and sources used in the rest of the plan.

Writing an executive summary well requires a lot of highly specialized knowledge of the film business. It’s not easy to attain that knowledge, but my free film business resource package is a great place to start! You’ll get a deck template, contact tracking templates, a FREE ebook, and monthly digests of blogs categorized by topic to help you know what you’ll need to have the best possible chance to close investors.

Here’s a link to the other sections of this 7 part series.

Executive Summary (this article)

The Company

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

5 Rules for Finding Film Investors

If you want to make a movie, you need money. If you don’t have money, you probably need investors. Here’s how you find them.

One of the most common questions I get is where to find investors for a feature film. Inherent in that question is simply where to find investors. While I may not have a specific answer for you regarding exactly where to find them, I do have a set of rules for figuring out where you might be able to find them in your local community. This is meant to be applicable outside of the major hubs in the US, and as such it’s not going to have to be more of a framework than a simple answer.

Would you rather watch or listen than Read? Here's the same topic on my YouTube Channel.

Like and Subscribe!

1. Go where the money is.

Think about where people in your community who have money congregate. In San Francisco, the money comes from tech. In Colorado, the money came from oil, gas, and tourism, but has recently grown to include legal recreational marijuana. In many communities, some of the most affluent are the doctors and medical professionals. In most communities, the local lawyers tend to have money, but you’ll have to make sure you come prepared. Figure out what industries drive your local economy and then extrapolate from that who might have enough spare income to invest in your project.

If you know what these people do, then you can start to figure out where they go when it’s after working hours. If you know where they go after hours, you can go get a drink and start to work your way to making a new friend in this investor.

All that being said, Be careful not to solicit too early, as that can actually be illegal. #NotALawyer.

2. Figure out a place where you can find something in common

Any investment as inherently risky and a-typical as the film industry relies heavily on your relationship with your investor. As such, finding something you have in common is a great way to start the relationship right.

RELATED: 7 Reasons Courting an Investor is Like Dating

As an example of what I mean, I’ve met investors while singing karaoke at Gay bars in San Francisco. I’ve met others at industry events, and I’ve even met a few by going to some famous silicon valley hot spots where investors and Venture Capitalists are known to congregate. If you know where all the doctors go to drink after work, and if there’s a regular activity at one of the bars that can facilitate meeting them, it might not be a bad idea to go and try to establish some connections in that community. This segues us nicely to…

3. Understand that moneyed people tend to have their own community

Generally, wealthy individuals know other wealthy individuals. If you develop a relationship with someone within that community, it means that even if that investor you ended up establishing a relationship with won’t invest, they may talk to a friend about it who might.

The reverse of this notion is also true. If you get a bad reputation in the Wealthy community then you’re likely to find it very hard to raise funds for your next film.

4. Understand that most people with money will have other investment options.

As stated above, film investment is highly volatile and inherently risky. If these investors took on every potential project that comes asking for their money, they would not be rich for very long. As such, you’re going to have lots of competition when it comes to raising funds for your film. This competition will not only come from other films, but also from stocks and bonds, other startups and small businesses, and even the notion that if they’re going to spend 100k they never get back, why not just buy a new Mercedes?

5. Find a not entirely monetary way to close the deal.

So to bring the last point home, you have to find other reasons that aren’t solely based on return on investment to get people to consider investing in your independent film. This can be the tax incentives, the moral argument to support culture, the fact that investing in a film is an inherently interesting thing to do, or a few other potential things. The blog below explores this in much more detail than I have the time or the word count to do here today.

Related: Why Don't Rich Tech People Invest in Film Part 5: Diversification and Soft Incentives

If you still need help financing your film, you should check out my free indiefilm business resource package. It’s got lots of tools and templates to to help you talk to distributors and investors, as well as a free-ebook so you can know what you need to know to wow them when you do. Additionally, you’ll get a monthly content digest to help you stay up to date on the ins and outs of the film industry, as well as be the first to know about new offerings and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media. Get it for free below.

The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Finance (And Where to Find the Money)

Financing a film is hard. It might be easier if you break it up into more manageable raises. Here’s an outline on that process.

Most of the time filmmakers seek to raise their investment round in one go. A lot of people think that’s just how it’s done. As such, they ask would they try anything else. If you have a route into old film industry money you can go right ahead and raise money the old way. If you don’t, you might want to consider other options.

Just as filmmakers shouldn’t only look for equity when raising money, Filmmakers should consider the possibility of raising money in stages. Here are the 4 best stages I’ve seen, and some ideas on where you can get the money for each stage.

1. Development

If you want to raise any significant amount of money, you’re going to need a good package. But even the act of getting that package together requires some money. So one solution to getting your film made is to raise a small development round prior to raising a much larger Production round.

If you want to do this with any degree of success, you’re going to have to incentivize development round investors in some way. There are many ways you can do it, but they fall well beyond my word count restrictions for these sorts of blogs. If you’d like, you can use the link at the end of the blog to set up a strategy session so we can talk about your production, and what may or may not be appropriate.

Related: 7 Essential Elements of an IndieFilm Package

Most often, your development round will be largely friends and family, skin in the game, equity, or crowdfunding. Grants also work, but they’re HIGHLY competitive at this stage.

Books on Indiefilm Business Plans

2. Pre-Production/Production

It generally doesn’t make sense to raise solely for pre-production, so you should raise money for both pre-production and principal photography. This raise is generally far larger than the others, as it will be paying for about 70-80% of the total fundraising. It can sometimes be combined with your post-production raise, but in the event there’s a small shortfall you can do a later completion funding raise.

It’s very important to think about where you get the money for the film. You shouldn’t be looking solely at Equity for your Raise. For this round, you should be looking at Tax incentives, equity, Minor Grant funding if applicable, Soft Money, and PreSale Debt if you can get it.

Related: The 9 Ways to Finance an Independent Film

Post Production/Completion

Some say that post-production is where the film goes to die. If you don’t plan on an ancillary raise, then too often those people are right. Generally you’ll need to make sure you have around 20-25% of your total budget for post. It’s better if you can raise this round concurrently with your round for Pre-Production and Principle Photography

The best places to find completion money are grants, equity, backed debt, and gap debt

4. Distribution Funding/P&A

It’s very surprising to me how difficult it is to raise for this round, as it’s very much the least risky round for an investor, since the film is already done.

Theres a strong chance your distributor will cover most of this, but in the event that they don’t, you’ll need to allocate money for it. Generally, I say that if you’re raising the funds for distribution yourself, you should plan on at least 10% of the total budget of the film being used for distribution.

Generally you’ll find money for this in the following places. Grants, equity, backed debt, and gap debt.

If you like this article but still have questions, you should consider joining my email list. You’ll get a free e-book, monthly digests of articles just like this, segmented by topic, as well as some great discounts, special offers, and a whole section of my site with FREE Filmmaking resources ONLY open to people on my email list. Check it out!

The 7 Essential Elements of A Strong Indie Film Package

If you want to get your film financed by someone else, you need a package. What is that? Read this to find out.

Most filmmakers want to know more about how to raise money for their projects. It’s a complicated question with lots of moving parts. However, one crucial component to building a project that you can get financed is building a cohesive package that will help get the film financed. So with that in mind, here are the 7 essential elements of a good film package.

1.Director

As we all know, the director is the driving force behind the film. As such, a good director that can carry the film through to completion is an essential element to a good film package. Depending on the budget range, you may need a director with an established track record in feature films. If you don’t have this, then you probably can’t get money from presales, although this may be less of a hard and fast rule than I once thought it was.

Related:What's the Difference between an LOI and a Presale?

Even if you have a first-time director, you’ll need to find some way of proving to potential investors that they’ll be able to get the job done, and helm the film so that it comes in on time and on budget

2. Name Talent

I know that some filmmakers don’t think that recognizable name talent adds anything to a feature film. While from a creative perspective, there may be some truth to that, packaging and finance is all about business. From a marketing and distribution perspective, films with recognizable names will take you much further than films without them. I’ve covered this in more detail in another blog, linked below.

Related: Why your Film Needs Name Talent

Recognizable name talent generally won’t come for free. You may need a pay-or-play agreement, which is where item 7 on this list comes in handy.

3. An Executive Producer

If you’re raising money, you should consider engaging an experienced executive producer. They’ll be able to help connect you to money, and some of them will help you develop your business plan so that you’re ready to take on the money when it comes time to. A good executive producer will also be able to greatly assist in the packaging process, and help you generate a financial mix.

Related: The 9 Ways to finance an Independent Film.

I do a lot of this sort of work for my clients. If you’ve got an early-stage project you’d like to talk about getting some help with building your package and/or your business plan I’d be happy to help you to do so. Just click the clarity link below to set up a free strategy session, or the image on the right to submit your project.

4. Sales Agent/Distributor

If you want to get your investors their money back, then you’re going to need to make sure that you have someone to help you distribute your independent film. The best way to prove access to distribution is to get a Letter of Intent from a sales agent. The blog below can help you do that.

Related: 5 Rules for Getting an LOI From a Sales Agent

5. Deck/Business Plan

If you’re going to seek investors unfamiliar with the film industry, you’re going to need a document illustrating how they get their money back This can be done with either a 12-slide deck, or a 20-page business plan. I’ve linked to some of my favorite books on business planning for films below.

6. Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Pro forma financial statements are essentially documents like your cash flow statement, breakeven analysis, top sheet budget, Capitalization Table, and Revenue Distribution charts that help you include in the latter half of the financial section of a business plan.

There’s a lot more information on these in the book Filmmakers and Financing by Louise Levinson. I’m also considering writing a blog series about writing a business plan for independent film. If you’d like to see that, comment it below.

7. Some Money already in place

Yes, I know I said that you need a package to raise money, but often in order to have a package you need to have some percentage of the budget already locked in. Generally, 10% is enough to attach a known director and known talent. If you’re looking for a larger Sales Agent then you’ll also need to have some level of cash in hand.

This is essentially a development round raise. For more information on the development round raises, check out this blog!

Thanks for reading, for more content like this in a monthly digest, as well as a FREE Film Market Resources Package, check out the link below and join my mailing list.

Check the tags below for related content.

6 Reasons Filmmakers Are Entrepreneurs

If you want to make movies for a living, you’ll likely have to start a company. That alone makes you an entrepreneur, but here are 6 other reasons why.

Filmmakers often don’t like to think of themselves as business people. Often, they’d rather be creative, and focus solely on the art of cinema. Unfortunately, this is not the way to create a career crafting moving images. In order to make a career, you must understand how to make money. The easiest way to do that is to think like an entrepreneur. here are 6 reasons why.

1. Filmmakers and Entrepreneurs both Must Turn an Idea into a Product.

At its core, the goal of both being a filmmaker and an entrepreneur is the same. To take an idea, and turn it into a market-ready product. For an entrepreneur, this product can be anything from software to food products, and everything in between. For a filmmaker, the product is content. Generally speaking, that content is a completed film, web series, or Television series.

This alone should be enough to see how filmmakers are entrepreneurs, but it’s not the only way the two job titles are similar

2. Filmmakers and Entrepreneurs are both creative innovators birthing something that has never been seen before.

Every successful company does something no one else ever has. Every successful film brings something that’s never been seen before to the market. Some innovations are minor, others major. Both sets of innovations are born by iterating on another idea that didn’t quite make their product in a way that the entrepreneur or filmmaker thinks is the best way.

Innovation is at the core of both filmmaking and entrepreneurship. Both involve intelligent and creative people who want to change the world. Some through technology, some through storytelling.

3. Filmmakers and Entrepreneurs both must figure out who will buy their product.

If either a filmmaker or an entrepreneur is to be successful, then they need to figure out who will buy their product when it’s ready to ship. If they don’t know what their target market is, then it’s impossible to make enough money to keep the company going or help investors recoup so you can make another film.

Market research is key to this. If you want to find out more, check out last week’s blog by clicking here.

4. Filmmakers and Entrepreneurs both often need to raise money to create their products.

While everything else on this list is true nearly 100% of the time, this one is only true 80-90% of the time. While some entrepreneurs and filmmakers can finance their companies out of pocket, most filmmakers need to consider how they’ll pay for the things necessary to create their chosen product.

Both filmmakers and entrepreneurs must develop a deep understanding of fundraising if they’re going to be able to make their career in their chosen field a long-term sustainable one.

5. Filmmakers and Entrepreneurs must both assemble a team to turn their idea into a product.

No one can make a film or build a company all by themselves. Both must build and manage a team of creatives and business people to create their product and take it out to the world. Without the ability to build and lead a team to success, the film or the company will not succeed.

6. Filmmakers and Entrepreneurs must both figure out how to take their products to market.

After coming up with an idea, figuring out who will buy their product, financing their vision, and assembling a team in order to create a product, filmmakers still need to get that product and figure out how to take it to market. For both, this is generally referred to as the distribution stage of the process.

For filmmakers, it’s relatively well-defined despite the information about it not being widely enough available. For entrepreneurs, their distribution plan will vary greatly by industry. But in either case, if the end user/viewer can’t access the product, they won’t buy it.

Thank you so much for reading. If you’d like to become a better indie film entrepreneur, you should check out my FREE Indiefilm Resource package. it’s got a free e-book called The Entrepreneurial Producer, several templates to help you organize your operation including a pitch deck template, and monthly blog digests to help you expand your knowledge base.

Check out the Tags below for more related content

Indiefilm Crowdfunding Timeline

In crowdfunding preparation is key, just as it is with filmmaking. If you want to succeed, you need to have a solid plan. Here’s a timeline that might help.

In crowdfunding as in filmmaking, preparation is key. If you don’t adequately prepare for your campaign, then you’re not likely to succeed. If you’ve never crowdfunded before, this can be a daunting prospect. Don’t worry, Guerrilla Rep Media is here to help. This post is meant to give you a timeline to prepare for your campaign, starting further out than you might think.

It’s based around what I’ve learned raising 33,000 of my own in the early days of kickstarter, as well as what I’ve learned from speakers and advising clients running their own campaigns.

6-12 Months Prior to Launch

Begin interacting with online and in-person communities relevant to your target market

If you want to have a chance at people outside of your friends and family donate to your crowdfunding campaign, then you’ll need to become a part of those communities early. If you show up and immediately start asking for money, you’re only going to lose friends and alienate potential backers and customers. If, on the other hand, you become part of the communities you’re targeting early on then you may well end up getting yourself some new audience members who might just back your campaign.

Related: 5 Dos and Don't for Selling your Film on Social Media

It’s a lot of work, but the benefits may surprise you. They’re likely to reach beyond your professional life, and into your personal life.

3 Months Prior To the Launch

Begin to be really active in groups of your target market.

Essentially, this is an extension of the list above. As your campaign approaches, spend more time engaging with people on those online communities you joined 3-6 months ago.

2 Months Prior to the Launch

Shoot Video

List All Potential Perks

Let People Know You'll be Running a Campaign

Get set up with your Payment Processor

About 2 months before your expected launch, you should get as much of the preparation out of the way as you can. This includes things like shooting your video, listing your potential perks, and potentially even getting set up with the payment processor of whatever platform you’re using.

Many of those things take much longer than you expect them to, so doing them early will make sure that your campaign launches smoothly.

1 Month Prior to Launch

Start seeing what press you can get.

Create a Facbook Event for Launch

Finalize list of Perks

Organize Launch Party

A month out from your campaign is when your pre-launch should be going into overdrive. You’ll need to issue a press release about your campaign to try to get some local press, make a Facebook event for the launch party to try to get some early momentum, finalize all your perks, and potentially organize a launch party to help get people excited about your project. You may want to consider making your launch party backer-only, just to get the numbers up early on. Let people donate at the door from their if you need to.

Related: Top 5 Crowdfunding Techniques

1 Week Prior to Launch

Do at least one press interview (if you can)

Promote Launch Day on Social Media

Confirm a few large donations to come in on lauch day: Ideally right at launch.

With your launch date less than a week away, you’ll want to see if you can get any press. This can be anything from a local newspaper from the town you grew up in, it could be a friend’s podcast, or it could even be some old high school alumni newsletter. The press will give you legitimacy and legitimacy means more backers.

While you’re doing this, you’ll want to spend a lot of time talking about the impending launch on social media and talking to some big potential donors about coming in in the first few hours of the campaign. If people see more traction early on, they’ll be more likely to jump on board.

Launch Day

Follow-up with AS MANY PEOPLE AS YOU CAN to get them to donate.

If you have some large confirmed donors, then you need to follow up with them and remind them on launch day. It matters a lot to get some big fish in right as the campaign starts.

First Few Weeks of the Campaign

INDIVIDUALLY email EVERYONE you can to ask them to donate.

Once you get your campaign started, you’ll want to INDIVIDUALLY email EVERYONE in your address book. I’m not talking about setting up and sending out a mail chimp email, I’m talking about individually reaching out to follow up with EVERYONE who you have an email for. One trick I’ve learned from a friend and Former Speaker Darva C. is that you should email 2 letters of the alphabet a day, over the first 2 weeks of the campaign. Then email them again, starting on day 16 of the campaign.

It’s a grind, but making a film always required sacrifice.

Midpoint of Campaign

Host an event to keep interested high.

It would be wise to have an event to keep your social media spirit high in the lull that is the midpoint of the campaign. You have to keep the momentum going through the campaign, so having something like a midpoint event to talk about on social media is incredibly useful. This event is one I would HEAVILY consider making backer-only, even if they’ve only backed you for 1 dollar. You could also let them back at the door from their phone.

Last Few Weeks of Campaign

Individually email everyone you can AGAIN.

Do the same thing that you did on the first 13 days of the campaign again. Thank the people who donated, and remind the people who didn't to donate again.

Closing Night-Host a celebration (or commiseration) party!

Finally, at the close of the campaign, you’ll need to have a party, whether to celebrate your success or commiserate that you didn’t hit your goal. Either way, you’ll deserve a night of fun because you WILL be tired.

If this seems like a lot, it is. Even once you’ve finished raising, you still need to make the movie. My free Film resource package includes a lot of resources to help you make it and get it out there once it’s done. It’s got a free e-book, lots of templates, and a whole lot more. Click the button below to sign up.

Click the tags below for more related content!

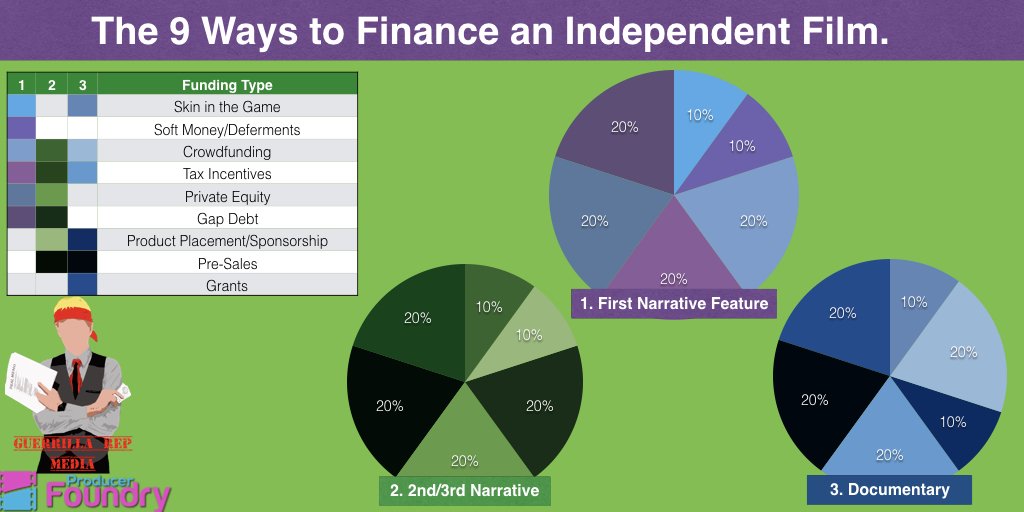

The 9 Ways to Finance an Indiependent Film

There’s more than one way to finance an independent film. It’s not all about finding investors. Here’s a breakdown of alternative indie film funding sources.

A lot of Filmmakers are only concerned with finding investors for their projects. While films require money to be made well, there’s are better ways to find that money than convincing a rich person to part with a few hundred thousand dollars. Even if you are able to get an angel investor (or a few ) on board, it’s often not in your best interest to raise your budget solely from private equity, as the more you raise the less likely it is you’ll ever see money from the back end of your project.

Would you Rather Watch or Listen than Read? I made a video on this topic for my YouTube Channel.

So here’s a very top-level guide to how you may want to structure your financial mix. The mixes in the image above loosely correspond to the financial mix of a first-time film, a tested filmmaker’s film, and a documentary. They’re also loose guidelines, and by no means apply to every situation, and should not be considered financial or legal advice under any circumstance. This is just the general experience of one Executive producer.

Piece 1 — Skin in the game. 10–20%

Investors want you to be risking something other than your time. The theory is that it makes you more likely to be responsible with their money if you put some of yours at risk. This can be from friends and family, but they prefer it come directly from your pocket.

I've gotten a lot of flack for this. However, the fact investors want skin in the game is true for any industry or any business. Tech companies normally have skin in the game from the founders as well, not just time, code, or intellectual property.