The 9 Ways to Finance an Indiependent Film

There’s more than one way to finance an independent film. It’s not all about finding investors. Here’s a breakdown of alternative indie film funding sources.

A lot of Filmmakers are only concerned with finding investors for their projects. While films require money to be made well, there’s are better ways to find that money than convincing a rich person to part with a few hundred thousand dollars. Even if you are able to get an angel investor (or a few ) on board, it’s often not in your best interest to raise your budget solely from private equity, as the more you raise the less likely it is you’ll ever see money from the back end of your project.

Would you Rather Watch or Listen than Read? I made a video on this topic for my YouTube Channel.

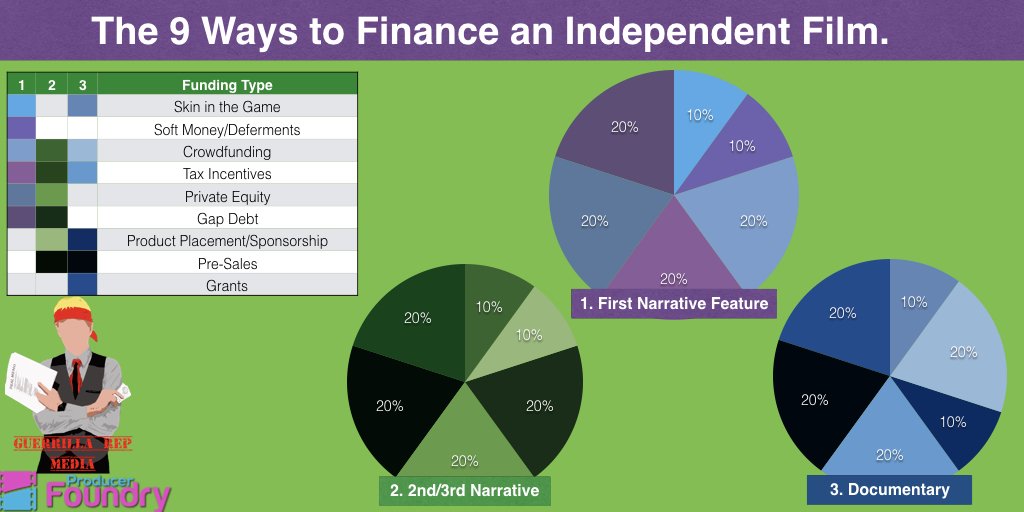

So here’s a very top-level guide to how you may want to structure your financial mix. The mixes in the image above loosely correspond to the financial mix of a first-time film, a tested filmmaker’s film, and a documentary. They’re also loose guidelines, and by no means apply to every situation, and should not be considered financial or legal advice under any circumstance. This is just the general experience of one Executive producer.

Piece 1 — Skin in the game. 10–20%

Investors want you to be risking something other than your time. The theory is that it makes you more likely to be responsible with their money if you put some of yours at risk. This can be from friends and family, but they prefer it come directly from your pocket.

I've gotten a lot of flack for this. However, the fact investors want skin in the game is true for any industry or any business. Tech companies normally have skin in the game from the founders as well, not just time, code, or intellectual property.

However, if you’ve got a mountain of student debt and no rich relatives, then there is another way…

Piece 2 — Crowdfunding 10–20%

I know filmmakers don’t like hearing that they’ll need to crowdfund. I understand it’s not an easy thing to do. I’ve raised some money on Kickstarter and can verify that It’s a full-time job during the campaign if you want to do it successfully. However, if you can hit your goal, not only will you be able to put some skin in the game, and retain more creative control and more of the back end but you’ll also provide verifiable proof that there’s a market for you and your work. Investors look very kindly on this.

That said, just as success provides strong market validation as a proof of concept, failing to raise your funding can also be seen as a failure of concept. and make it more difficult to raise than it would otherwise have been. Make sure you only bite off what you can chew.

Due to the difficulty in finding money for an independent film, the skin in the game or crowdfunding portion of the raise for a director’s first project is often a much higher percentage of the raise than it will be for their future projects.

Piece 3 — Equity 20–40%

Next up is equity. This is when an investor gives you money in return for an ownership stake in the company. From a filmmaker's perspective, it’s good in that if everything goes tits up, you don’t owe the investors their money back. Don't misunderstand what I mean by this. You ABSOLUTELY have a fiduciary responsibility to do your due diligence and act in the best interest of your investors to do absolutely everything in your power to make it so they recoup their investment. If you do that, or if you commit fraud, your investors can and likely will sue the pants off of you. You’ll have an uphill battle on that as well since they probably have more money for legal fees than you do.

Also, you will need a lawyer to help you draft a PPM. You shouldn't raise any kind of money on this list without a lawyer, with the possible exception of donation-based crowdfunding or grants. In general, just remember that I’m a dude who produced a bunch of movies who writes blogs and makes videos on the internet. Not a lawyer or financial advisor. #Notlegaladvice #Notfinancialdvice #mylawyermakesmewritethesesnippets.

It’s bad in that if everything goes extremely well, they get a huge percentage of your film. So it deserves a place in your financial mix, but ideally a small one.

For a longer list of my feelings on this topic, check out Why film needs Venture Capital, or One Simple Tool to Reopen Conversations with Investors

Piece 4 — Product Placement 10–20%

Product placement is when you get a brand to compensate you for including their product in your film. It’s more common in the form of donations or loans for use than hard money, but both can happen with talent and assured distribution. If you’re a first-timer, it’s difficult to get anything other than donated or loaned products.

Piece 5 — Presale Backed Debt 0–20%

Everything you read tells you the presale market has dried up. To a certain degree, that is true. However, it’s more convoluted than you may think. According to Jonathan Wolfe of the American Film Market, the presale market has a tendency to ebb and flow with the rise and fall of private equity in the filmmaking marketplace. There’s been a glut of equity for the past several years that’s quickly drying up.

That said, there are a lot of other factors that will determine where pre-sales end up in a few years. The form has shifted, in that it’s generally reputable sales agents that give the letters instead of buyers and territorial distributors. You then take that letter to a bank where you can borrow against it at a relatively low rate.

Piece 6 — Tax incentives 10%-20%

While many states have cut their filmmaking tax incentives, it’s still a very viable way to cover some of the costs of making your project. It is worth noting that the tax incentive money is generally given as a letter of credit, which you can then borrow against or sell to a brokerage agency. It’s not just a check from the state or country you’re shooting in. This system of finance is significantly more viable in Europe than it is in the US, but no matter where you plan on shooting it needs to be part of your financial mix.

Piece 7 — Grants 0–20%

There are still filmmaking grants that can help you to make your project. However, that’s not something that is available to all filmmakers, especially when they’re first making their projects. Don’t think grants don’t exist for you and your project, because they probably do, spend an afternoon googling it. My friend Joanne Butcher of www.FilmmakerSuccess.com suggests applying for one grand a month for the indefinite future, as when you do so you’ll develop relationships with the foundations you contact which can be invaluable for your career growth.

Grants are much easier to get as a completion fund once you’ve shot your film. Additionally, films made overseas are more likely to be funded by grants than those shot here in the US.

Piece 8 — Gap/Unsecured Debt 10–40%

Gap debt is an unsecured loan used to create a film or television series. This means that the loan has no collateral, be it product placement, Presale, or tax incentive. It used to be handled by entertainment banks for a very high interest rate, I can’t say who my source was on this, but I have heard of interest rates in excess of 50% APR. That market has been largely taken over by private investors loaning money through slated, which did bring interest rates down. Unsecured debt almost certainly requires a completion bond, which generally means that it’s only suitable for projects over 1mm USD in budget.

In general, you should use this form of financing as little as possible, and pay it back as quickly as possible. Again, Not legal or financial advice.

Piece 9 — Soft money and Deferments — whatever you can

Soft money is funding that isn’t given as cash. This can be your crew taking deferred payment for their services, or receiving donated or loaned products, locations, and anything else meant to get your film made. This isn’t so much funding as cost-cutting. It often includes donations or loans from product placement.

If you like this content and want to learn more about film financing, you should consider signing up for my mailing list. Not only will you a free e-book, but you’ll also get a free deck template, contract tracking templates, and form letters. Plus you’ll stay in the know about content, services, and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media.

How do we Get More Investors into Independent Film?

How do we get more investors in the film industry? We improve the viability of film as an asset class. Here’s how.

Throughout writing this blog series, I’ve been told more times than I can count that film is a terrible investment, and no one besides hobbyists would consider it. Many want to leave it there, without bothering to look at what’s causing it. Last week we thoroughly examined the issues plaguing the film industry, and what keeps investors out. The issues aren’t pretty, but they may be fixable. What follows is a list of what could be done to fix this problem and some of the ways organizations that are implementing these tactics.

Greater Transparency

One of the biggest things stopping film investment is the perception that it’s unprofitable. All too often that’s not simply a perception. Another thing stopping independent film as an industry from being profitable is the fact that many sales agents don’t accurately report the earnings of the films they represent. Others charge too much in recoupable expenses, so it’s unlikely to recoup. Some take an unreasonable portion of the revenue or simply hide sales from filmmakers.

One necessary problem to fix is the lack of transparency within distribution. There are rights marketplace solutions like Vuulr and RightsTrade emerging thanks to recent technologies for international distribution. Aggregators like BitMax and FilmHub have been around for a while already. The issue that these platforms have yet to solve is that of both audience and industry awareness of their project. If a filmmaker can market or receive help with that audience discover and marketing, then in theory the entire process can be disintermediated and filmmakers can sell directly to customers using a marketplace. Unfortunately, this discovery issue is still both time-consuming and expensive.

What about a hybrid system? One where a skilled group works with distributors and sales agents to sell the completed films at the maximum possible profit to the investors and production company. What if those groups were directly linked to protecting the investor’s interests, and gives sales agents capital for growth and new projects? Then the sales agents would have much better incentives to ensure the companies that license their content to them get a strong return.

That would seem like a solution, but we’ll get to it. There are other problems to delve into first.

Better Business Education for Filmmakers.

I touched on this in my last blog, but filmmakers don’t understand the business well enough to function as media entrepreneurs. Traditionally, specialists such as executive producers, PMDs, and true producers focused on the marketing and supported projects so that the writers, directors, creative producers, and line producers could focus on making the project. With film sets getting leaner, there aren’t enough of media entrepreneurs doing their jobs. (although I take on this role from time to time.)

In essence, there isn’t enough of a skilled entrepreneur class capable of making and selling films as a product either directly to consumers or to distributors, sales agents, and other industry outlets. So long as filmmakers don’t understand business, they’ll never be able to break out and get what they and their films are worth. If filmmakers don’t endeavor to understand business, they will be unable to communicate with investors and understand where they come from well enough to make a sustainable living in film. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that film schools don’t teach any of these skills as well as they should.

Filmmakers want to make the movie, and they will stop at nothing to get that done. As a result, promoting the film becomes an afterthought far too often. What would be ideal is if these educational organizations could tie into an angel investment group or community.

But what about integrating with an investor class and/or investment group?

Educated Investor Class

Investors generally understand business, but the film industry is ripe with its own nuances and idiosyncrasies. Investors need to know how money flows from them to create the product, then to take the product to market through various forms of distribution, and how that money eventually gets back to that same investor. Investors need tools to tell when someone is offering a con instead of an investment. It’s not the easiest thing to find information on, and when they do it’s focused more on the filmmaker than the investor.

If an investor doesn’t understand the issues within the film industry, then it’s less likely they’ll be able to properly vet an investment. If that same school that teaches filmmakers business, could teach investors about the nuances involved in the film industry, then there could be something of a connection point at a different sort of event.

Curators and tastemakers with Access to MEANINGFUL Distribution.

Just because an investor knows about how money comes in and out of the film industry doesn’t mean they can find quality films in which to invest. Being a professional Investor is all about quality deal flow. Indiefilm success tends to make less money than a successful technology startup, so curation and guidance is even more important.

Sure, nobody knows everything, but a curated eye can help separate the wheat from the chaff. Most investors don’t have a trusted source to review projects for feasibility and potential returns. Investment is about more than just money. Investors often act as business advisors. Unfortunately, not enough angel investors understand the industry well enough to do that effectively. However, if the curation board also acted as advisors on the projects, then the potential returns get much higher.

As an example, if that board had access to distribution, then you could cut out the biggest risk of investing in film. A member of the curation board could get the films to the proper PayTV, TVOD, SVOD and other distributors to help the fund managers.

A way of Discovering new talent

It’s always been a problem to find the next Quinten Tarantino, Jennifer Lawrence, or Jason Blum. Everyone has heard stories of how everyone in Hollywood is related. While it's more true than anyone wants to admit, the on set path to grow your career has become more difficult and less sustainable than it once was.

It's not an easy problem to solve. It’s difficult to tell the difference between that person who’s DEFINITELY going to be the next big thing but ends up washing cars two years later and the dweeby 20 year old who no one thinks will ever make anything of themselves makes millions at the box office on their directorial debut. This problem may be the most difficult of any listed.

Making your first film is incredibly difficult. It’s also very difficult to get it financed. From an investor perspective, they put in all the money up front ant they’re the last to be paid. It’s incredibly high risk with little reward.

Marketing a film is also quite difficult, and generally involves additional expenditure when the coffers are dry. This has killed many films before they saw the light of day. If a fund were to offer finishing funds to new filmmakers, they keep their risk incredibly low while opening up new discovery options.

Sure, it doesn’t help get the film made in the first place, but it can help get it finished and out there. The barrier to entry of having a nearly completed film also cuts down on the pool of potential applicants in a way that necessitates them showing they have the mettle to actually make something. That fund could also give preference to successful filmmakers for their second, third, and fourth projects. Such a system could enable a fund to retain the quality people they need to make a successful organization, while still opening the ranks for discovery.

Staged Financing

Investment in film is inherently speculative an as a result incredibly high risk. But the risk could be made lower by borrowing some techniques from Silicon Valley VCs. Instead of funding 100% of a film upfront in equity, an investor could stage their investment over the course of the film, at key points where the filmmakers would require more money.

It’s not something that could be done with a simple line in the sand due to the difficulty in getting recognizable name talent on board the project, but there are systems that could be used to mitigate risk while maintaining the ability to make high-quality name-driven projects that have a higher chance of financial success than directorial debuts with no names attached. It’s not a magic bullet, but it could mitigate the problem enough for other solutions to be more possible.

Staged financing would make it much more approachable for investors, since the risk to the individual investor is significantly smaller. But there are ways an organization could further limit the risk. How you ask?

Same Funder Providing different securities.

As mentioned in part 6 of this series, equity investors are the last to be paid on most projects due to where they fall in the waterfall in relation to Platforms, Distributors, Sales Agents, and the like. This is due in part to filmmakers needing to secure debt-backed securities from different funders in order to complete the project. These debt-backed securities must be paid before the investors are, which further disincentives the equity investment from the original investors.

But what if the different securities were made available from the same group? That way a fund could offer the same pool of investors the last in first out debt in order to protect the interest in their equity position. From my vantage, that would seem to protect both the investor and the filmmaker by enabling the investor to mitigate risk and the filmmaker to maintain greater ownership of their projects, and a higher profit share once the debt is paid off.

Thanks for reading. This one required A LOT of rewriting as part of the archive transfer/website port. If you made it this far, you should sign up for my email list to get my free film business resource pack. You’ll get blogs just like this one segmented by topic, as well as a free e-book, investment deck template, contact tracking templates, form letters, and more!

Check out the tags below for more related content!

6 Things stopping a sustainable investor class in film.

If you’ve ever raised money to make a film, you know it’s hard. It’s not because individual films can’t be good investments, it’s that the problems with the industry are systemic. Here’s a look at why.

Much of this series has been focused on the numbers behind film investment. While metrics like ROI and APR are very important when considering an investment, they’re not the only reason that high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) tend to shy away the film industry. Here are 6 things that are stopping them.

In order for independent film to develop a sustainable investor class, the asset class itself needs to be taken more seriously. The reason that no one has yet been able to create a sustainable asset class out of film and media is much more complicated than the numbers not being in our favor. In this post, we’re going to examine some of the other things stopping independent film from becoming a sustainable asset class. This list is in no particular order, except how it flows best.

1. LACK OF INVESTOR EDUCATION

Investors tend not to invest in things they don’t know or understand, at least as anything more than an ego play. The Economics behind film investment is difficult to understand even before you factor in how difficult it is to find reliable information on film finance from an investor’s perspective.

Even the basics of the industry can be difficult to learn. Generally, film investors are forced to read older, often out-of-date books on film financing targeted more at filmmakers than at investors. This industry is in the midst of a reformation, so much of the information is out of date before it’s published. Most investors don’t really spend a long time learning information from a different perspective which may or may not be correct.

Whit that in mind, many Investors learn how money flows in the Film industry from the filmmakers they invest in. Apart from the conflicts of interest, there’s another rather large problem with that strategy.

2. FILM SCHOOLS DON’T TEACH BUSINESS AS WELL AS THEY NEED TO

Film Schools can be great at teaching you how to make a film, but they’re generally not good at teaching necessary business skills. Even things as basic as general marketing principles, how best to finance a film, or how to make money with a film under current market conditions.

While film and media are an artistic industry, focusing solely on the quality of the film is not going to recoup the investor’s money. Film Schools aren’t great at teaching branding filmmakers how to define their core demographic, or how to access them once they have.

3. DISTRIBUTION ISN'T WHAT IT USED TO BE.

The big risk in film distribution used to be the gatekeepers. You had to make a good enough film to attract a distributor so you could get your film out there. However, that problem has been traded for an entirely different one, oversaturation of content. I would argue that a new problem is harder to overcome.

The old model was that the home video sales would be able to make a genre film profitable, even if it wasn’t that good. Essentially, if you had access to a wide-scale VHS or DVD replicator, you could make a mint selling the licenses. There wasn’t much competition, so a cottage industry sprung up around film markets.

That model worked when it was much more expensive to make a film. Given the high barrier to entry from needing to raise enough money to shoot on film, as well as develop the skills to expose it correctly, there was relatively little competition compared to the demand. However, now that anyone can make a film with an iPhone and 500 bucks the marketplace has been flooded.

Additionally, since the DVD Market has all but dried up, it’s difficult to make a return for newer filmmakers. VOD (Video On Demand) Numbers haven’t risen to the occasion, since most people can get their fix from watching Netflix. It used to be easy to sell DVDs as an impulse buy at the checkout line. Now that everyone has hundreds of free movies at their fingertips, Why should they pay 3 bucks to watch something when there’s an adequate alternative I can get for free?

So the problem is now less how to get distribution, and more how to market the film once you’ve got it. It’s both hard and expensive to market a film. Generally, it’s best to create something of a hybrid between these two types of Distribution. However, there are issues with that as well, and these are less associated with expertise.

4. SEVERE LACK OF TRANSPARENCY IN INDEPENDENT FILM

I’ve written before about the lack of transparency in Distribution, so I won’t go into too much detail here. In Essence, the black box that is the world of film distribution is very intimidating to many investors. Investors want to be able to know when their money is coming back, and many filmmakers are unable to make any real promises about that. However, there’s another issue with transparency from an investor’s perspective.

Unfortunately, many filmmakers don’t communicate well with their investors or other stakeholders. I’ve spoken with many film commissioners, investors, and others about their frustrations with filmmakers not keeping them in the loop.

Filmmakers understandably focus on the admittedly difficult task of making the film happen. Between all of the tasks like scheduling and budgeting the film, finding the locations, confirming the crew, making the shotlist and storyboards, sending out call sheets, and a whole lot more, it’s easy to let communication fall by the wayside.

5. INVESTORS LAST TO BE PAID

Now I know that Filmmakers are reading this thinking “BUT I GET PAID AFTER THEY GET 120% BACK!?!?” To a level, you’re right. However, unless you waived your producer’s fees, you got paid before they did. Sure, you did a lot of work for often too little money to make your film happen, but you did get a fee to produce this film. If your investor wanted to be cynical about it, you produced or directed a movie for hire that you got to take most of the credit for.

Here’s what a waterfall for a film normally looks like. Investors generally did a lot of work to get their money, and now they’ve paid you to make a film and it’s unlikely they’ll ever get all of their money back.

1.Buyer Fees

2.Sales Agent Commission

3.Sales Agent Expenses

4.SAG/Union Residuals

5.Producers Rep (If Applicable.)

6.Production Company

7.Gap Debt (+Interest)

8.Backed Debt (+Interest)

9.Equity Investor

I may be persuaded to do a financial analysis of what that would actually look like in terms of money. Oh look, I did a blog explaining exactly what this means. Click here to read it.

6.LACK OF ACCESS TO TASTEMAKERS AND CURATION

We explored the numbers of why indexed film slates just don’t work in part two. However it takes a fair amount of training, experience, and a bit of luck to recognize what films will hit and what films won’t. While William Goldman is famous for saying “nobody knows anything,” there has to be a balance between a dart board with script titles and industry experts guiding the ship.

Developing an eye for what makes a successful film is something that most prospective film investors don’t want to take the time to learn, especially since many get burned on their first investment. it takes a lot of time to understand what projects have what fit in the market, and that’s generally not something that an investor has time for.

Having a few sets of experienced eyes looking over what investments would be good to fund is something that could make independent film a more sustainable asset class, and not enough investors have access to it to avoid getting burned.

So, what is there to be done about it? Check the next post for the final installment, How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Also, if you like this content you can get a lot more of it through my mailing list. You’ll also get a FREE film business resource package that includes an investment deck template, contact tracking templates, money-saving resources, a free e-book, and a whole lot more. Again, totally free. Get it below.

Click the tags below for more articles on similar topics.

Diversification and soft incentves in the film industry.

Film tends to not be an attractive investment, but it has some unique advantages that help it stand out and can make it worth your investors giving you the money you need to make your project. Here’s a few of them.

In this blog series, we’ve been talking a lot about why filmmakers would invest in an independent Film. Sadly, if you go by numbers alone the answer is that they shouldn’t. Film investment is an unpredictable, volotile, high risk endeavor. But, if you’re the type that isn’t scared by that, there are some reasons to considerer it. Sure, it will probably never make you as much money as tech, but it might has other benefits that aren’t offered by tech investment.

1. Smaller Potential Downside

If a Tech company fails to exit, generally you’re out everything you put in. Films exit once they’re completed, and investors begin recouping when they do. Further, a smart filmmaker won’t fund their project solely by equity, si the investor is more likely to get their money back. So, while you may not have be able to find a decacorn, the potential to lose everything you put in is somewhat less likely. It can be even less likely if you invest in finishing funds.

2. Tax Credits

Nobody likes to pay Uncle Sam, most people would rather see their name in lights than pay the government. Many states offer a tax incentive to get filmmakers to attract productions outside of territory. Often, those incentives are structures as tax credits an investor could buy at about 85-90 cents on the dollar. Other commissions offer it as a rebate that goes back to the filmmakers and subsequently back to the investors, if it’s not re-invested to finish the film.

3. Diversification

A strong investment portfolio is a diversified investment portfolio. Some industries do better than others when times are tough. Historically, Film is a sector that’s somewhat reversely dependent on the economy. That means when there’s a downturn, film investments sometimes do better. The period of greatest growth was in the great depression, and until recently it’s still been one of the least expensive ways to get out of the house.

But will that continue to be true? Perhaps not. Theater sales are continually declining, and DVD sales are in the toilet. However, in todays world, most independent films never get a theatrical release. if they can market themselves to the right audience, they can still make sales to people in their homes, for less than a cup of coffee. Admittedly that marketing job is no small feat.

Even if you don’t want to invest in social activism, you can enable an artist to create something that brings joy into the hearts of countless people. Sometimes by scaring the pants off of them. The arts are more than just storytelling, they help us communicate who we are as a people. In many ways I know more about Luke Skywalker than I do about my uncle, and more about Harry Potter than most of the people I went to my real high school with. These cultural touchstones have a huge impact on who we are as a society.

The US is terrible about helping to fund the arts and culture, so to some degree it comes down to society itself to perpetuate it’s own culture. If you can afford to help filmmakers make better movies, you should consider it

4. Supporting Arts and Culture

While every cultural or artistic entrepreneur should learn how to make their money back, it’s not the sole purpose of any cultural or artistic endeavor. It’s about communicating an idea, perhaps for entertainment or perhaps to spend a different level of consciousness.

If there’s a cause you care about, you should fund some filmmakers looking to do more to spread awareness of that cause. Then when you tell your friends to watch it to share your views, you also get the benefit of making a sale. Many ideas were only able to take root through the power of mass media.

5. Non-monetary incentives.

We all have hobbies, most of them cost us far more than they make us. If you’re the sort of person who can afford to lose 5 figures here or there, investing in films can be very interesting. if you can’t afford quite that much, you may want to look into different funds. I’m in the process of starting one, you can find out more here.

Some of my best friends became my friends because we talked about the money behind the film industry. These non-monetary incentives might even be useful sooner than you would think. If you start networking with filmmakers you may even get a deal when it comes time to make your next whiteboard video from the filmmakers you invested in.

6. Do something other people aren’t

I hear you. that Nerd you were shouting in #4 has been replaced by hipster. Don’t worry, you’re about to go back to nerd, since I’m going to lay some science on ya. If we look at the general attractiveness of beards, we learn that as they’re less common, they’re more attractive. Now, whether or not to invest in film is a multifaceted concept. I’m not saying ti will help you find a lady, (or gentleman,) but I am saying that it’s almost certain to start an interesting conversation.

If you’re at a Silicon Valley Networking event, it’s important to seem like a very interesting person. The same is true for any party. Attraction is somewhat based on scarcity, so you want to stand out from the pack. Investing in films is a good way to do that. You never know how it might help you stand out from the pack and talk to that person over by the bar with their eye on you, be it for your interesting investment or your beard.

7. Glitz and Glamour

If you’re a tech investor, you may have made a lot of investments that made you a very good return. Some of them may have been solely for the strong potential for ROI, or because the entrepreneurs could execute and build something that made a return. It could have changed the world of B2B Payroll invoicing. But while those make a difference in the lives of many myself included, it’s not really exciting.

Film is different. You get to meet interesting creative people. You get to talk about things other than how that API with that box shaped thing that processes your payments isn’t working as you planned, or the calendar integration isn’t as easy as it should be. You get to see what happens on set, or what it was like meeting that guy from that Quinten Tarantino movie for a day. And when you’re done, you can talk to the people at the tech event and share some awesome stories.

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back with more next week about why more people don’t invest in film. In the meantime, if you want to consider investing in film, try joining Slated. They’re a great resource to help you find projects that give you the best chance at a return. While all of the things above are great, they’re not worth losing every cent you put in. Slated helps you rate your projects, and find the ones with the best chance of success.

This entire 7-part series examines why film is an unsustainable investment. Part of the reason for the lack of sustainability is the fact that not enough producers understand the investment metrics of the film industry, and not enough filmmakers understand the business side of their craft. To help counter this, I offer all of these blogs plus a FREE film market resource pack on you can get by clicking below. If you want to take your career to the next level, the resources it has in it are a great place to start. Plus you’ll get monthly blog digests with recommended reading to help you parse through the 100+ blogs on my site and more easily reference them when you need them.

the 5 Main Types of Indiefilm Distribution Media Rights - Redux

Indpendent films are sold based on 3 major criteria. Media Rights, Territory, and Language. Here’s an overview of the first.

Distribution deals tend to confuse and confound many filmmakers. While there are a lot of complicated places that revenue can get lost, the essence of distribution deals is quite simple. They’re essentially just parsing of different media rights to various territories around the world. However given the Black Box that is the world film distribution, it’s often unclear how these rights get structured. So with that, I thought it prudent to share some of the structure of these deals.

Generally, these rights are broken up both by territory and by media type. This post is by type, there will be a future post based on territory. Generally, you’ll need a very skilled Producer's Rep or a sales agent to sell these territories for you. Click here to find out the difference between those two.

Type 1: Theatrical

This should be fairly clear. Theatrical rights are for the rights to release in theaters. Again, this is usually done by territory. Producer’s Reps may help with this domestically, but you will generally need a sales agent to sell it internationally if you want a hope at getting any significant number of screens. You’ll also need a genre film to get a screen guarantee from a distributor.

There are a few other types of exhibition that would fall under this right umbrella. Education rights with classroom or school screenings are an example, as are community screenings that would take place at a venue other than a traditional theater. This right is generally quite easy to negotiate a distributor taking non-exclusive rights so you can exploit it yourself.

Type 2: Physical Media (I.E. Home Video/DVD/Blu-Ray)

Believe it or not, there is still a market for DVD and Blu-ray. A lot of it is international, but there are still major retailers like Wal-Mart, target, and occasionally Redbox. These are as they sound, and are most often sold to a sales agent who then sells them to wholesalers. There are also outlets that can help you self-distribute those rights, Allied Vaugn will even let you sell through major online storefronts including all the major places you can think of. These deals are normally done through a process known as Manufacture On Demand, or MOD. In general, if you can only find a title online, it’s probably fulfilled through a MOD process.

Type 3. Television Rights

In General, these rights are broken out into 3 sub categories, PayTV, CableTV, and FreeTV.

PayTV

Pay TV is essentially Premium TV. These are places like HBO, Starz, Showtime, etc. These deals are generally exclusive, and will often also include a Subscription Video On Demand (SVOD) license. This is so that the network can include the offering on their associated SVOD platforms and extensions through third-party services like Hulu or Amazon Prime.

For instance, this allows HBO to put the content on HBOMAX or Discovery+. There’s an ongoing shakeup in the SVOD space, but that’s better left for the SVOD section.

CableTV

Cable TV is as it would sound. It’s any channel accessible via terrestrial cable or satellite television. These providers have been largely consolidated and tend to pay significantly less than payTV outlets for independent films, although there are some notable exceptions to this rule. These outlets are less likely to take SVOD rights, but they’re not at all uncommon to be included in such a license.

More commonly, these outlets will take Free Ad-Supported Streaming Television Services (FAST) or Ad-supported Video on Demand (AVOD) rights. More on that in the VOD section.

In general, these networks survive on ad revenue and carriage fees. Ad revenue should be clear if you’re reading this, but carriage fees are a fee paid to each individual channel from every single cable subscription which includes that channel in its bundle.

Free/Network TV

As it would sound, Network or Free TV is for the major “Over the air” networks. In The US, These would be ABC, NBC, Fox, and CBS. Most of the time these channels will be accessible solely with an antenna. These are almost entirely supported by ad revenue, but they do get carriage fees from cable providers as well.

Type 4: VOD

VOD stands for Video On Demand. There’s more than one type of Video on Demand Service, and each type has different providers. Here’s a very brief outline of what the different types of VOD are, and some samples as to the people who provide that service.

-TVOD

This stands for Transactional VOD. This has largely replaced Pay Per View television rights and is generally the most accessible form of VOD. There are many platforms for PPVOD. The most obvious would be iTunes, Google Play, Amazon/Createspace, and Vimeo On Demand. Amazon is far and away the largest TVOD platform in terms of gross sales. Most films I worked on had between 60 and 80% of total TVOD sales come in through Amazon.

-SVOD

Subscription Video on Demand – [SVOD] is for VOD platforms that run on a subscription basis. This would be platforms like Netflix, and Hulu Plus, as well as extensions of PayTV and regular TV channels as mentioned above.

-AVOD/FAST

Ad supported Video on Demand (AVOD) are apps where you can watch content on demand for free with ads. Platforms for this are Tubi, Vudu Free, or even YouTube. (you should check me out there, ;) ). Free Ad Supported Streaming Television Services (FAST) aren’t technically VOD, as they’re not on demand. These platforms continually stream channels of content similar to cable television but deliver over the internet as opposed to being bound by terrestril cable or satelite. The most notable example of this is PlutoTV.

Type 5 - EST & Ancillary

EST refers to Electronic Sell Through. This is functionally what used to be known as Pay Per View, and is generally when you rent a movie through a cable or satellite box. Comcast InDemand and driectTV are good examples. Ancillary rights rever to any method of watching content outside of the standard methods listed above. Airlines and Cruise Ships are common examples. Airlines and cruise ships tend to exist outside of territorial rights though. Hotels, academic, or library rights may be considered ancillary right types as well.

Thank you so much for reading! In the process of porting my old website over to my new host, I realized this blog in particular needed A LOT of updating, so I hope you enjoyed it. If you did, please share it with your filmmaking community.

If you want more like this, you should consider signing up for my resource package. You’ll get monthly blog digests segmented by category and a heaping helping of templates, money-saving resources, and even an e-book! Join below.

If this is all a little intimidating and you feel like you need a guide to navigate distribiution, you should check out guerrilla rep medi services. If you want something even more in depth, we have books and courses you can check out, and if you just feel like more of this information should be be widely available, support me on substack or patreon. My main gig is actually financing and distributing films, so having a bit of money coming in helps keep me writing content just like this. Thanks so much!

What does a Producer’s Rep Do Anyway?

Outside of the film industry, few people understand what a producer does. Inside of the indusrt, the jargon gets even deeper. This article examines the difference between Agents, Executive Producers, Producer’s of Marketing and Distribution, and Producer’s reps, as well as their roles and responsibilities.

As stated in the article What's the difference between a sales agent and a distributor, one of the most common questions I get is What does a producer’s Rep Do? Since that post teaches the major distribution players are by type, (you should read it first.) I will now thoroughly answer what a producer’s rep does.

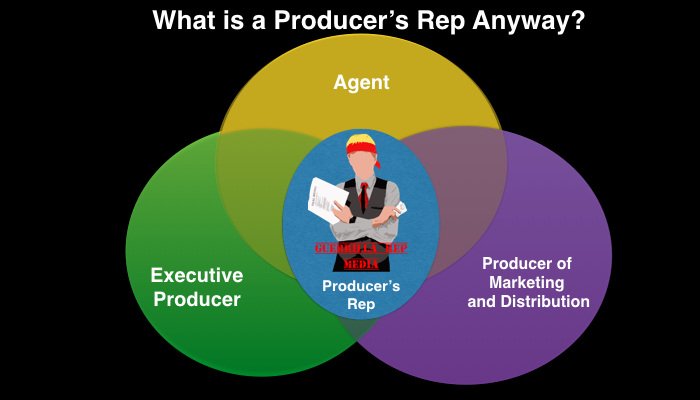

Simply put, a Producer’s rep is a mix between a PMD and an executive producer. A Producer’s Rep takes on a lot of the business development jobs for a film. We wear a lot of hats. Most often we'll connect filmmakers with completed projects to sales agents and negotiate the best possible deal. We're skilled negotiators with a deep knowledge of the film distribution scene, and entrenched connections there.

Would you rather watch or listed to a video instead of reading an article? Check out this video on my youtube channel for most of the same information.

If a producer's rep comes on in the beginning, we’ll do the job of an executive producer. We'll help you finance the film in the best way possible. not just through equity investment, but planning proper utilization of tax incentives, pre-sales, crowdfunding, occasional product placement, and sometimes helping to connect you to some of our angel contacts. That said, if we’ve never met, you have no track record and want us to start raising money for you, that probably won’t happen.

Not all producer’s reps will work with first-time directors and producers, I will, but generally only on completion or near the end of post-production. I will not help someone who I have not worked with before garner investment for their projects, except in very limited circumstances. I will help filmmakers get their financial mix in order. If a rep makes connections for investment, we need to know if the filmmakers I'm working with can deliver a quality product and get our investment contacts their money back.

A Good Producer’s Rep will also be able to act as a PMD, or at least refer you to a good one. We don't just work in traditional distribution, but we can help plan and implement other tactics including proper use of VOD. We’ll help you plan your marketing and distribution, then we’ll tell you how to implement it, helping you along the way. We’ll help you develop the best package in order to mitigate the risk taken by our investors. If we do bring on investors, you’d best believe we’re with you through the end of the project, to make sure that everyone ends up better off. We’ll check in and act as a coach to help you grow to the next level.

In a lot of ways, we’re agents for producers and films. Good reps, like good agents, won’t just think about this project, they’ll help you use your projects to move to the next step in your career.

So how do you pay a Producer’s Rep? Since the services we offer are so varied, our pay scale is as well. Some things are based primarily on commission. Sometimes that commission will come with a small[ish] non-refundable deposit that would be things like connecting to distribution. That commission is generally around 10%, but can range between 5-15%. Some things [like document and plan creation] are a flat fee, others are hourly plus commission on completion. That would apply primarily to packaging.

It is worth noting that not all producers reps are trustworthy. There are some that charge 5 figures upfront with no guarantee of performance. Admittedly, no one can guarantee they can sell your film, or get it financed investment. If they guarantee it and ask for a large upfront payment, you should be very wary of them. However, there are some with a strong track record of doing so. Just as you would when talking with sales agents, talk to people who have worked with them in the past.

Most reps will give you a discount based on doing multiple services. Remember to check last week's post for an idea of what each major player in indiefilm distribution Does!

If reading this made you think you want a producer’s rep, check out the Guerrilla Rep Media Services section!

If you like this content but aren’t ready to look into hiring us, but would like educational content you should for my Resources list to receive monthly blog digests segmented by topic. Additionally, you’ll get a FREE E-book of The Entrepreneurial Producer, plus a heaping helping of templates and money-saving resources to make your job finding money or the right distribution partner significantly easier.

What’s the Difference between a Sales Agent and Distributor?

Too few filmmakers understand distribution. Even something as basic as the disfference between each industry stakeholder is often lost in translation. This blog is a great place to start

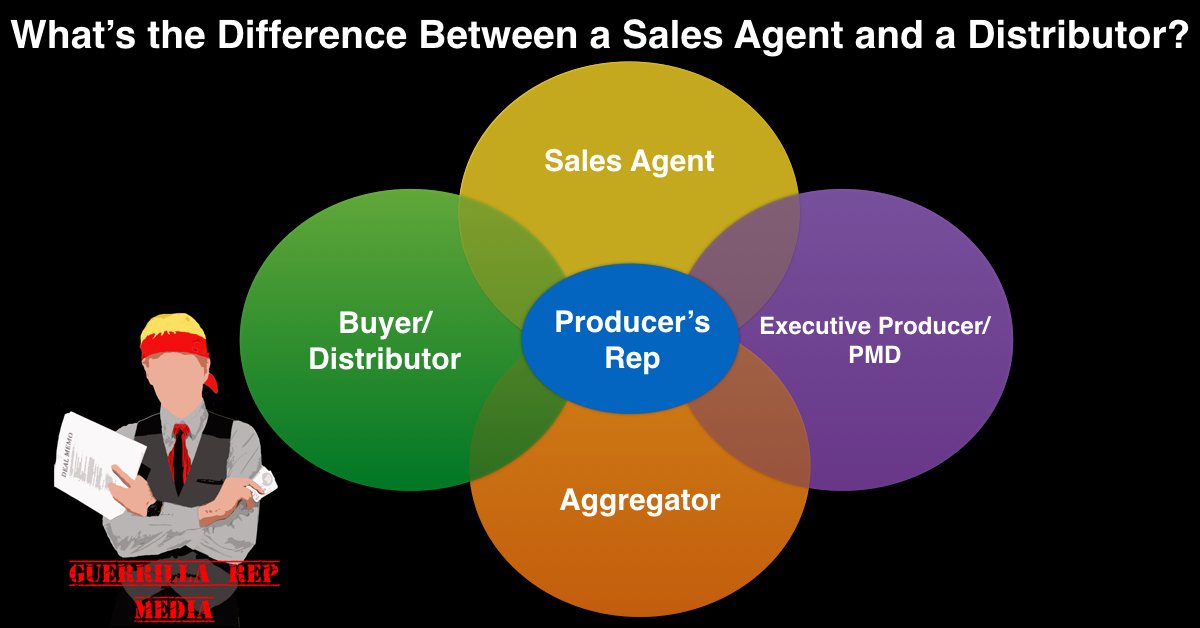

As a Producer’s Rep, one of the questions I get asked the most is what exactly do I do? The term is somewhat ubiquitous and often mean different things to different people. So I thought it might be a good idea to settle the matter. In this post, I’ll outline what a producer’s rep is, and how we interact with sales agents, investors, filmmakers, and direct distribution channels. But first, we need a little background on some of the terms we’ll be using, and what they mean. These terms vary a bit depending on who you ask, but this is what I’ve been able to gather.

Would you rather watch/listen than read? Here’s a video on the same subject from my Youtube Channel.

Like and Subscribe! ;)

DISTRIBUTOR / BUYER

A distributor is someone who takes the product to an end user. This can be anything a buyer for a theater chain, a PayTV channel, a VOD platform, to an entertainment media buyer for a large retail chain like Wal-Mart, Target, or Best Buy. The rights Distributors take are generally broken up both by media type and by territory.

For Instance, if you were to sell a film to someone like Starz, they would likely take at least the US PayTV and SVOD rights, so that it could stream on premium television and their own app which appears on other SVOD services like Amazon Prime, or Hulu. They make take additional territories as well.

Conversely, it’s not uncommon to sell all of France or Germany in one go. It should are often sold by the language, so sometimes French Canada will sell with France. This is less common as of late.

Generally, these entities will pay real money via a wire transfer, and almost deal directly only with a sales agent. Although sometimes to a producer’s rep, and VOD platforms will generally deal with an aggregator. The traditional model of film finance is built around presales to these sorts of entities, but that presale model has recently shifted.

Recently, more sales agents have begun distributing in their territory of origin. XYZ is a good example of this. Some distributors have branched out into international sales. This is something that we did while I was at the Helm of Mutiny Pictures, to allow us to deal with filmmakers directly in a more comprehensive way.

Sales Agents

A Sales agent is a person or company with deep connections in the world of international sales. They specialize in segmenting and selling rights to individual territories. Often, they will be distributors themselves within their country of origin. This business is entirely relationship based, and the sales agents who have been around a while have very long-term business relationships with buyers all around the world. That’s why they travel to all of the major film markets.

Examples on the medium-large end would be Magnolia Pictures international, Tri-Coast Entertainment, and Multivissionaire. WonderPhil is up and coming as well, as is OneTwoThree Media. Lionsgate and Focus Features would also be considered distributors/sales agents, but they’re very hard to approach. They also both focus on Distribution over sales.

Generally, these sales specialists will work on commission. They may offer a minimum guarantee when you sign the film but that is not common unless you have names in your movie. Generally, they will charge recoupable expenses which mean you won’t see any money until after they’re recouped a certain amount. In general, these expenses will range between 10k and 30k, with the bulk falling between 20 and 25k. If it’s higher than 30k without a substantial screen guarantee, you should probably find another sales agent. There are ways around this, but I’ll have to touch on this in a later blog [or book].

A sales agent commission will be between 20% and 35%, this is variable depending on several factors, but generally 25% or under is generally good, and over 30% is a sign you should read more into this sales agent. Lately, this has been trending towards 20% with a slight uptick in expenses.

Aggregators

Aggregators are companies that help you get on VOD platforms. The most important service they provide is helping you conform to technical specifications required by various VOD platforms. This job is not as easy as you would think it is, which is why they charge so much. Additionally, they have better access to some VOD platforms than others. These days, it’s very difficult to get on iTunes or most platforms other than Amazon’s Transactional section without one.

Generally, aggregators charge a not insubstantial fee to get you on these platforms, and they offer little to help you market the project. Companies like this include Bitmax and arguably filmhub or IndieRights.

There are merits to going this this route, but they can be expensive, often costing about one thousand USD upfront and growing from there. If they operate on a commission like Filmhub or Indierights, they won’t help you with marketing so you’ll have to spend a decent amount there in order to get your film seen.

Producer of Marketing & Distribution (PMD)

In the words of Former ICM agent Jim Jeramanok, PMDs are worth their weight in gold. A PMD is a producer who helps you develop your marketing and social media strategy, your Festival strategy, and your distribution strategy. They’re also quite likely to have some connections in distribution. They’re there to give your film the best possible chance at making money when it’s done.

Generally, they’re paid just as any other producer would be, but if they’re good, they’re worth every penny. With a good PMD on board, your project’s chances for monetary success are exponentially better.

If you’re an investor reading this, you want any film you invest in to at least have access to a PMD or Producer’s Rep, if not a preferred sales agent or at least domestic distribution. (Not Financial Advice)

Executive Producer (EP)

In the independent film world, these are producers who are hyper-focused on the business of independent film. They either help raise money to make the film, or they help bring money back to those who put money into it in the first place. As such, the traditional definition in of an indiefilm executive producer is someone who helps you package projects by attaching, bankable talent, investors, or other forms of financing. They’ll also help you design a beneficial financial mix, [I.E. where can you best utilize tax incentives, presales, brand integration, and equity, and gap debt.] in order to help your project have the best chance of success. They can also play a significant role in distribution. The latter is where most of my EP credits come from.

Often, they’ll take a percentage of what they raise or what they bring in. sometimes they’ll require a retainer, but most of the time they should have some degree of deliverables such as business plans, decks, or similar as part of that. These fees should not be huge, but they will be enough to give you pause due to the amount of specialized work involved in doing these jobs.

Producer’s Reps

I’ll go into this much more deeply next week, But Producer’s Reps are essentially a connector between all of these sorts of people and companies. Producer’s Reps will connect you do sales agents, aggregators, buyers, and investors. But more than that, a good one will help you figure out how and when to contact each one. Most often, they’re credited as an executive producer or a consulting producer as the PGA does not have a separate title that applies to this particular skillset. For a more detailed analysis of what exactly a Producer's Rep does, Check out THIS BLOG!

Thank you so much for reading! If you found it useful, please share it to your social media or with your friends IRL. If you want more content like this in your inbox segmented by month, you should sign up for my resources pack. I send out blog digests covering the categories and tags on this site once per month. You’ll also get a free EBook of The entrepreneurial producer with this blog and 20 other articles in it, as well as templates, form letters, and money-saving resources for busy producers.

If this all seems like a lot, and you need your own personal docent to guide you through the process, check out the Guerrilla Rep Media Services page. If you’d rather just get a map or an audio tour and explore the industry on your own, the products page might have some useful books or courses for you. Finally, if you just appreciate the content and want to support it, check out my Patreon and substack.

Peruse the tags below for related free content!

Why Film Needs Venture Capital

Part of creating a sustainable revolution in the film industry is creating a new system of finance. For that, we should look to other industries starting with Private Equity and Venture Capital. Here’s how we do that.

A lightbulb next to a chart outlining the allocation of venture funds in 2011 above a text blurb outlining the data source.

There’s an old joke that goes something like this. Three artists move to Los Angeles, a Fine Artist, a poet, and a Filmmaker. The first day they’re in town, they check out the Mann’s Chinese Theater. When they get there, a wave of inspiration overtakes them. The fine artist says, “This is incredible, I have to draw something! Does anyone have a piece of chalk?” Low and behold a random passerby happens to have one, and hands it over. The fine artist does a beautiful rendering on the sidewalk.

Watching this, the poet says, “I’ve had a flash of inspiration, I must write! Does anyone have a pen and paper?” It happens to be a friendly sort of Los Angeles day, and someone hands over a pen and paper. He writes a beautiful Shakespearean sonnet about his friend’s artistry with the chalk.

The filmmaker says “This is amazing, I’ve got to make a movie about it! Does anyone have any money?”

Even though the costs of making a film have been cut drastically, the joke remains true. I mentioned in my last post that the film world is in need of new money, and that what the film world really needs is something akin to Venture Capital. I think the topic deserves more exploration than a couple paragraphs in a post about transparency.

Venture capitalists bring far more than money to the table. They also bring connections and a vast knowledge of financial and industry specific business knowledge to the table. Essentially these people are experts at building companies, and when you really break it down the best films really are just companies creating a product.

The contribution of connections and knowledge is just as vital to the success of the startup as the money is. We have something somewhat similar in the film world, it’s generally the job of the executive producer to find the money for the film and put the right people in place to run the production and complete the product.

The biggest problem is that good executive producers with contact to money are few and far between, and there are very few connection points between the big money hubs and the independent film world. Filmmakers often don’t only need money, they need to have an understanding of distribution and finance that many simply do not have, and most film schools just do not teach. These positions are generally not full time positions, and most filmmakers just don’t have the money they need to pay people like this. If a venture capital model were to be adapted in film, the firm could link to these experts, and included in the budget for the film at a cost far less than it would normally be, because the person could split their time between all of the projects represented by the firm.

Most people understand that filmmakers need money, what many people do not understand is that there are very valid reasons for an investor to invest in film.A good investor knows that a diverse portfolio is far better than one that focuses solely on one industry. Industries can change and the revenue brought in by any single industry can crash with little notice. Savvy investors will seek to have money in many pots as it really helps to weather through downturns. Film is considered to be a mature industry, and has grown steadily over the past several years, even in the economic downturn. In fact, the film industry is moderately reversely dependent on the economy, so it often does better in economic downturns.

The biggest problem is that most investors just don’t invest in things they don’t know. Investors need to understand an investment before they put money into it.

Film is a highly specialized and inherently risky business. All the money goes away before any comes back, and that can scare off many investors. Especially since they often don’t understand what a good use of resources for a film is and are often incapable of seeing when the project should be stop-lossed as to not lose any more money.

One solution a venture capital firm could bring to this industry that single investors simply cannot is stage financing. Stage financing is a system of finance that is widely used in Silicon Valley. The concept is basically that the investors only release funds once certain checkpoints are met. Single angel investors do not have the time or expertise to act in this way, which is a big part of the reason for the standard escrow model. If a project that makes it through the screening process is only given the money they need for pre production up front, they must pass a review to have funds released for principle photography then it becomes a far more sustainable investment.

Filmmakers may balk at the idea of review, but quite frankly so long as the production is being well managed, they should be able to complete the checkpoints and have the additional funds released with little difficulty, assuming that the right review panel is put in place. The fund itself has every reason to see it’s projects through to completion, so it will only be filmmakers who are not doing their jobs that end up not passing the review process.

Edit: Additionally, there are deals that can be made to help agents and bankable talent feel more comfortable with such a process. This may be a subject of a later blog, and is mentioned in the comments.

Why does the fund have every reason to see films through to completion? Because if the films are not completed, then the fund will have lost all the money it put in with no chance of getting it back. That said, if the production is a disaster, and it’s clear that additional funds would not actually result in a finished and marketable film, then it is far better to cut losses and move on with other projects that have higher potential for revenue.

As mentioned in the last blog, a lack of transparent accounting is also a big issue with investors.

A single filmmaker does not really have the ability to negotiate with a distributor, at least not to a level necessary to resolve the transparency issue. In the relationship, the distributor has all of the power and there’s really very little most filmmakers, especially those just starting out, can do to change that.

But in film as in any industry, money talks. If there were a venture capital firm for film that only worked with distributors who have transparent books, and those distributors could then turn around and propose new projects to the venture capital firm, then some of the issues of transparent accounting could start to change. Many distributors, especially those working in the low budget sphere, are continually raising money for their own projects. So, having a good relationship with a venture capital firm is a big incentive to maintain good books and responsible business practices for filmmakers.

It got listed in the comments section of Black Box that filmmakers shouldn’t necessarily need to have that much business sense, since it takes their whole being to create. Filmmaking is indeed a collaborative effort, and it’s not a director’s job to think about target demographics and marketing strategies. The problem is the people in the film world that truly understand investment and recoupment are few and far between. Many of them also take advantage of filmmakers, as evidenced by the stories of studio accounting from Black Box. Part of what’s needed is the creation of teams that have what it takes to both tell quality stories with high production values, also get the films to market and figure out exit strategies, target demographics, and general budget recoupment tactics.

Many Film Schools just don’t teach this part of the business. Film schools focus everything on how you can make the film, and what it takes to do it, but few of them really give you the ability to actually go raise money. So what’s really needed is a new class of producer that understands the executive side. What’s really needed is a new class of investor that understands what it takes to invest in film, the risks, the rewards, and how it’s diversified. What’s really needed in film is a company that can successfully link the two together, and create a new class of media entrepreneur. What’s really needed is an incubator for independent film with a team that can execute both of these aspects and create a sustainable business model out of it.

Right now no such organization really exists. Legion M has some elements of it, but they miss the new talent discovery elements in favor of risk abatement. Slated works similar to AngelList, but I’m not sure their track record is what it needs to be to justify their price point. I’ve been trying to start one between my various projects with angel groups, Mutiny Pictures, Producer Foundry, and other ventures. It’s clear that the industry is changing, but quite frankly it needs to. The best way to effect the change in practices that need to happen in the industry is to change the way the industry is financed. The entrance of a film fund that operates on principles more akin to the aspiraations of a venture capital firm would do just that, and is exactly why it needs to happen.

If you enjoyed this blog, please share it to your social media. You should also join my mailing list for some curated monthly blog digests built around categories like financing, investment, distribution, marketing, and more. As well as some templates (including a deck template) as well as other discounts, templates, and other resources.

Check out the content tags below for related content

Black Box - a Call for Transparency in Film

The concept that Film Distributors aren’t telling you the whole truth isn’t unknown. However, the problem is deeper than you may realize. Here’s why.

A Black cube on grass in a yard, with the Title “Black Box” in the upper left corner and the subtitle “An In Depth Analysis of ‘Hollywood accounting” in the lower right corner, and logos for Guerrilla Rep media and PRoducer Foundry in the lower left corner.

Photo Credit thierry ehrmann Via Flickr, Modifications made to add title, subtitle, and logos

The process of Filmmaking has been evolving rapidly over the past decade. With the massive change in the availability of equipment, negating the need for tapes or stock, and bringing the professional quality down to a price point thought unfathomable merely a decade ago, the barrier to entry for making a film has been almost completely obliterated. Additionally, education on how to make a film has become widely available, from the massive emergence of film schools to a plethora of information available in special edition DVDs, anyone can learn how to make a film. However, the same cannot be said for Film Distribution. Film distribution is still a black box from where no light or information emerges. There is a very palpable air of secrecy around film distribution, and now that film production has become available for anyone curious enough to seek it, it’s time the same is done for film distribution.

I’ve always loved movies, and I’ve been making films in some fashion for nearly a decade. Even though that’s really not that long, I realized that when I started, camcorders were still fairly rare among middle-class families, and far rarer among high school students. Even the local Access channel worked with three-chip cameras, and those who could afford it swore by the film. That landscape is now nearly unrecognizable, now every other high school freshman carries a 1080p camera in their back pocket anywhere they go. This process has been going on for decades, far longer than my personal experience.

In the 70s, even Super 8 home movies were few and far between. To make a movie in the 70s involved an incredible amount of time, effort, and skill. Many learned by trial and error, with limited training and education often in the form of watching the great films of their eras. In those days, no one went to Film School, because there really weren’t that many of them. You pretty much had to go to New York or LA.

Even those who entered the industry in the 60s and ’70s often went to school for something else. Today, there are 389 Film Schools spread across 43 states, which considerably changes the landscape for Education.

However the same cannot be said for film distribution. Despite the fact that technology has evolved beyond what even the most visionary filmmakers could scarcely imagine back in the 70s. Much of it is still a black box where even the most simple information about budgets and returns are kept largely under lock and key. Studio accounting and net proceeds are just as secret now as they have been since Jimmy Stewart became the first Actor to be a net profit participant back in the 50s.

Even if you made a film that’s being represented by a distributor, many of them will not share accurate information regarding the returns you’ve made. A simple balance sheet is difficult to track down, and even if you can get one it’s often hindered by studio accounting, and the breakeven point is never reached, so the filmmaker never sees his or her share in the net proceeds, also known as profit participation. If filmmakers don’t make money making films, then all they have is an expensive hobby that is unsustainable in the long term. The problem is so vast that even Star Wars Episode 6 never made a profit. Even if they can get their first project bankrolled, unless they can make a profit on their film it is unlikely that they will get to make another one. In the independent film world, most times if the producer never sees their share in the net proceeds, then neither does the investor who footed the bill.

If the investor doesn’t see profit, then they won’t be an investor for long. Unlike the filmmaker, most of them won’t continue to do this just for the vision. The first thing any savvy investor will tell you is that they only invest in what they know. And while they may now be easily able to find information on the process of making the film, the metrics measuring the performance of independent films are unclear and almost always unreliable. If an investor can’t decode and project revenue through clearly definable analytics, most of them are far less likely to close an investment deal. Even if they do invest, if they feel like the distributor is not telling them the whole story, they generally won’t invest again.

If the Industry is to change, new money to enter it. The old money is tied up in sequel after sequel, and rehashes of old stories. The movie-going public is fed up with it and want something new, different from the old franchises. This leaves a demand in the industry for quality content that is simply not being filled to the extent it needs to be. In a way it’s similar to the ’60s and early ’70s here in San Francisco when Venture Capital was just starting, there are many talented young people with great ideas, but little business sense.

The studios are entrenched in the old ways of thinking, and behemoth companies don’t adapt well to change. Startups do adapt well to change, and they really can change thought processes through ideas that take hold. The Film Industry is changing more rapidly than ever before, it will likely be just as unrecognizable in another 5 years as it was 10 years ago. Anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The old companies and the old money can’t adapt as quickly as things are changing, so logically we need new ideas and new money to enter the industry and shake things up.

This is exactly the effect that Venture Capital had when the Traitorous Eight left Shockley Semiconductor to start Fairchild, and then left to start other companies that eventually became Silicon Valley. Fairchild was only able to be started due to a new idea that evolved into what is now known as Venture Capital. In order to effect change as quickly as is needed, something similar must happen in the film industry. But Venture Capital can’t enter an industry where the risks are incalculable. Without a more transparent method of accounting, the risks are indeed incalculable.

The industry is evolving more rapidly than ever before. The future is unclear. It’s a wide-open frontier where anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The process of film production has moved out from the dark rooms and light-proof magazines of old and exposed for all to see. It is time for the business side to do the same. It is time for every filmmaker and investor to have a clear understanding of Distribution. It is time for daylight to expose the studios’ accounting practices. It is time for transparent accounting in film.

While there's not a lot an individual can do about the lack of transparency in the film industry as a whole, there are ways that we as individuals can band together to have an impact. Those tactics are some of what I tried to implement at Mutiny Pictures, and what I address in my content, groups, and consulting. One of the goals of porting over my website was to greatly lessen advertising and sales, but check the links below to learn more about ways you can impact not only your career but the industry as a whole. More details on each of the buttons found below.