The 5 Pervasive Issues Preventing the Emergence of New US Film Hubs

If you want to succeed as an indie filmmaker, you need to have a network and a community. Trouble is the only major film communities in the US are New York, LA, and Atlanta. What’s stopping us from fixing that? This blog identifies problems we need to solve to expand beyond the coasts.

If you’re a filmmaker, you probably already know a lot of other filmmakers in your area. If you don’t, you should. That’s one reason why film community events are absolutely vital for the independent film industry. It’s far from the only reason that communities of independent filmmakers are vital for your success as an independent filmmaker.

I’ve been involved with a few film community organizations ranging from Producer Foundry to Global Film Ventures, and even the Institute for International Film Finance. I’ve also spoken at organizations across the country. From the experience of running more than 150 events and speaking for a few dozen others, I’ve noticed some commonalities across many burgeoning independent film communities, so I thought I would share some of my observations as to why most of them aren’t growing as quickly as they should. Without further ado, here are the 5 pervasive problems preventing the growth of regional film communities.

Lack of Resources

It’s no secret that most independent films could use more money. It’s true for film communities and hubs as well. In general, most of these community organizations have little to no money unless they’re tied to a larger film society or film festival. Unfortunately being tied to such an organization often prevents the work of community building due to the time and resources involved in the day-to-day operations of running a film society or the massive commitment that comes with running a film festival.

Compounding the issues with a lack of resources is that a community organization built to empower a regional film community isn’t something that you could raise equity financing from investors. Projects like this are much better funded using pages from the non-profit playbook. There are organizations looking to write grants specifically for film organizations seeking to empower communities. You can find out more about the grant writing process in this blog below.

RELATED: Filmmakers! 5 Tips for Successful Grantwriting.

While local film commissions do provide some support to locals, their primary mandate is generally built for a different purpose that I’ll discuss in the next of my 5 points.

Most tax incentives emphasize attracting Large Scale Productions, not building local hubs

Most film tax incentives are heavily or sometimes even entirely oriented on attracting outside productions as a means to bring more revenue to the city, state, region, or territory. This is understandable, as many film commissions or offices are organized under the tourism bureau or occasionally the Chamber of Commerce. Both of those organizations have a primary focus on attracting big spenders to the local area in order to boost the economy.

RELATED: The Basics of Film Tax Incentives

This mandate isn’t necessarily antithetical to the goal of building local film communities. There is nearly always a local staffing requirement for these incentives, and you can’t build an industrial community if no one has work. Some of the best incentives I’ve seen have a certain portion of their spending that is required to go to community growth, as San Francisco’s City Film Commission had when I last checked. Given that the focus of the film industry is focused on attracting outside production, there is often a vacuum left when it comes to building the local community and infrastructure as a long-term project.

Additionally, given that film productions are highly mobile by their very nature using tax incentives to consistently attract large-scale projects is almost always a race to the bottom very quickly. If a production can simply say to Colorado that they’ll get a better deal in New Jersey, then the incentive in Colorado fails its primary purpose. Eventually, these states or regions will continue a race to the bottom that fails to bring any meaningful economic benefit to the citizens of the state. While the studies I’ve seen on this often seem reductive and significantly undervalue the soft benefits of film production on the image and economy of a state, the end result is clear. If all states over-compete, eventually the legislatures will repeal the tax incentives. After that, outside productions will dry up.

When this happens, local filmmakers are left out in the cold. The big productions that put food on the table are gone, and there’s no meaningful local infrastructure left to fill the void that the large studio productions left.

Creating a film community is a long-term project with Short Term Funding.

It takes decades of consistent building to create a new film production hub. People often have the misconception that Georgia popped up overnight, and this isn’t true. While the tax incentive grew the industry relatively quickly on a governmental timescale, I believe the tax incentive was in place for nearly a decade ahead of the release. Georgia’s growth was greatly aided by local Filmmaker Tyler Perry’s continual championing of the region as a film hub.

Most of the funding apparatuses available for the growth of film communities are primarily oriented toward short-term gains. That makes long-term growth a difficult process, but if cities and regions outside of NY, LA, and ATL are to grow it needs to be a part of the conversation.

There are some organizations out there pushing to build long-term viable film communities outside of those major hubs. Notably, the Albuquerque Film and Music Experience has a great lineup of speakers for their event in a few weeks. I’m one of those speakers, so if you’re in the area check it out, and check out this podcast I did with them yesterday.

It’s hard to bring community leaders together

As I said eat the top, I’ve been involved with and even run several community organizations. One consistent theme I’ve noticed is that most community leaders are very reticent to work with each other in a way that doesn’t benefit them more than anyone else. This means that one issue I’ve seen consistently is that while there are disparate factions of the larger film community throughout most regions it’s nearly impossible to bring them together to build something big enough to truly build a long-term community.

Most filmmakers and film community leaders are much happier being the king of their own small hill than a lord in a larger kingdom.

Filmmaking is a creative pursuit, and it requires some degree of narcissism to truly excel. This is amplified when you run a local film community. Sayer’s Law states: “Academic politics is the most vicious and bitter form of politics because the stakes are so low.” If you replace the word “Academic” with “Filmmaking” can be said for the issue facing most film communities. Call it Yennie’s Law, if you like. #Sarcasm, #Kinda.

I discussed this in some detail with Lorraine Montez and Carey Rose O'Connell of the New Mexico Film Incubator in episode 2 of the Movie Moolah podcast, linked below.

The industry connections for large-scale finance and distribution generally aren’t local.

If you’ve read Thomas Lennon and Robert Ben Garant’s book Writing Movies for Fun and Profit you’ll already know that LA is the hub of the industry, and if you want to pitch you need to be there. Given the fact I live in Philadelphia, I believe it should be fairly clear I disagree with the particulars of the notion the overall sentiment remains true. Also, if you haven’t read it click that link and get it. It’s a great read. (Affiliate link, I get a few pennies if you buy. Recommendation stands regardless of how you get it.)

If you want to make a film bigger than at most a few million dollars, you’re going to need connections to financiers and distributors with large bank accounts. You can find the distributors at film markets, but all of the institutional film industry money is in LA. While you may be able to raise a few million from local investors, it’s really hard and it is an issue facing the growth of independent film communities nationwide.

Another issue is around the knowledge of the film business and the logistics of keeping a community engaged and organized. While I can’t help too much with the latter, I can help you and your community organizers on the knowledge of the film industry with my FREE film business resource Pack! It’s got a free e-book, free macroeconomic white paper, free deck template, free festival brochure template, contact tracking template, and a while lot more. Just that is more than a 100$ value, plus you also get monthly content digests segmented by topic so you can keep growing your film industry knowledge on a viable schedule. Click the button below!

As I said earlier, I’m speaking at AFMX this year. If you like this content and you’d like to have me speak to your organization, use the button below to send me an email.

Check the tags below for more related content!

The Basics of Financing your Independent Film with Tax Incentives

Making a profit on an indie film is HARD. If you can get your film subsidized by a tzx incentive your job is a lot easier. Here are the basics to get you started on that path.

Most filmmakers simply chase equity in order to finance their films. However, most investors don’t want to shoulder the financial risk involved in a film alone. That’s where tax incentives for independent film can come in and help to close the gap. But proper use of tax incentives for independent film financing is somewhat complicated. Here’s a primer to get you started.

Cities, States, Regions, and countries can have tax incentives

First of all, it’s important to understand that most forms of government can issue a tax incentive. In the US, the biggest and best incentives generally (but not always) come from states, however many cities, counties, and regions may supplement those incentives with smaller Internationally, many countries also provide some level of subsidy.

Europe Tends to provide better tax incentives than the US.

From the standpoint of the federal government, most European countries are much better about independent film subsidies than the US. Most of the time, these incentives take the form of co-production funding, but it’s relatively common for film commissions to provide grants to help promote the arts among their citizens.

This is particularly notable given that citizens of EU Member States can strategically stack incentives in a way that the majority of your film is financed via government subsidies. If, like me, you are based out of the United States, that’s just not possible due to the structure of most tax incentives.

There’s normally a minimum spend.

Especially in the US, there’s generally a fairly hefty minimum spend to qualify for a tax incentive. In some states that spending can start around 1 million dollars for out-of-state productions. Some states offer a lower cap for productions helmed by residents of the state.

There’s generally a minimum percentage of the total film budget needing to be shot there.

Most of the time you’ll only be eligible for a tax incentive if you shoot a certain percentage of your film or spend a certain percentage of your budget in a given territory. These can vary widely from territory to territory so look at the first place.

It’s normally not cash upfront

Unless you’re getting a grant from whatever film commission you’re shooting in, you’re probably just going to get a piece of paper that will state that you will be audited after the production and paid out according to the results of the audit. There are generally a few different ways that a tax incentive can be structured, but we’ll touch on those next week.

You need to plan for monetizing it.

In general, you’ll either end up selling the tax incentive for a percentage of its total value to a company with a high tax liability in your state, or you’ll have to take out a loan against your tax incentive in order to get the money you need to make the film. Both of these incur some level of cost which is different depending on which state you’re shooting in.

For example, Georgia and Nevada both have transferrable tax credits. Due to the large amount of productions going on in Georgia on a pretty much constant basis, the transferrable tax credit often monetizes at around 60% of face value. Nevada on the other hand has relatively few productions and many casinos that have very high tax burdens. As a result, the tax incentive in Nevada tends to monetize at around 90%. That said, there is presumably a more tested, experienced crew in Georgia than in certain parts of Nevada, of course, the film commission will tell you differently.

Not everything is covered

Not every expense for your film is covered. Exactly what is covered can vary widely from state to state, but in general only expenses that directly benefit the economy of the state are covered. There are often exceptions. One common exception is some mechanism to allow recognizable name talent to either be included in a covered expenditure or at least exempted from minimum thresholds of state expenditures.

Most of the time, high pay for above-the-line positions such as out-of-state recognizable name talent or directors are not covered covered by tax incentives. However, there are a few states that allow it. I talk a lot about it in this Movie Moolah Podcast with Jesus Sifuentes, linked below.

Related Podcast: MMP:003 Non-Traditional Investors & Maximizing Tax Incentives W/ Jesus Sifuentes

Not every program is adequately funded

Many film programs have a “cap” If that cap is too low, the money can be gone before the demand for the money is. Some states have the opposite problem.

Communicating with the film commission pays dividends long term

In general, the film commissions I’ve talked to are extremely friendly and easy to talk to. However, many times these commissions lose touch with the filmmakers they’re supporting shortly after they shoot. This isn’t necessarily a good thing, as most film commissions have significant reach into the greater film community and other aspects of local government. If you make sure they stay up to date as to what’s going on with your project you may find yourself getting help from unexpected places.

Also, if this is all a bit complicated, you should check out this new mentorship program I’ve started to help self-motivated filmmakers get additional resources as well as get their questions answered by someone working in the field. It’s more affordable than you may think. Check out my services page for more information.

If you’re not there yet, grab my free film Business Resource package. It’s got a lot of goodies ranging from a free e-book, free white paper, an investment deck template, and more. Grab it at the button below.

Finally, If you liked this content, please share it.

Click the Tags below for more, related content!

Filmmakers Glossary of Film Business Terminology.

I’m not a lawyer, but I know contracts can be dense, confusing, and full of highly specific terms of art. With that in mind, here’s a glossary of Art. Here’s a glossary to help you out.

A colleague of mine asked me if I had a glossary on film financing terms in the same way I wrote one for film distribution (which you can check out here.) Since I didn’t have one, I thought I’d write one. After I wrote it, it was too long for a single post, so now it’s two. This one is on general terms, next week we’ll talk about film investment terms. As part of the website port, I’m re-titling the first part to a general film business glossary of terms, to lower confusion on sharing it. It’s got the same terms and the same URL, just a different title.

Capital

While many types exist, it most commonly refers to money.

Financing

Financing is the act of providing funds to grow or create a business or particular part of a business. Financing is more commonly used when referring to for-profit enterprises, although it can be used in both for profit and non-profit enterprises.

Funding

Funding is money provided to a business or non-profit for a particular purpose. While both for-profit and non-profit organizations can use the term, it’s more commonly used in non-profit media that the term financing is.

Revenue

Money that comes into an organization from providing shrives or selling/licensing goods. Money from Distribution is revenue, whereas money from investors is financing, and donors tend to provide funding more than financing, although both terms could apply.

Equity

A percentage ownership in a company, project, or asset. While it’s generally best to make sure all equity investors are paid back, so long as you’ve acted truthfully and fulfilled all your obligations it’s generally not something that you will forfeit your house over. Stocks are the most common form of equity, although films tend not to be able to issue stocks for complicated regulatory reasons and the fact that films are generally considered a high-risk investment.

Donation

Money that is given in support of an organization, project, or cause without the expectation of repayment or an ownership stake in the organization. Perks or gifts may be an obligation of the arrangement.

Debt

A loan that must be paid back. Generally with interest.

Deferral

A payment put off to the future. Deferrals generally have a trigger as to when the payment will be due.

“Soft Money"

In General, this refers to money you don’t have to pay back, or sometimes money paid back by design. In the world of independent film, it’s most commonly used for donations and deferrals, tax incentives, and occasionally product placement. It can have other meanings depending on the context though.

Investor

Someone who has provided funding to your company, generally in the form of liquid capital (or money.)

Stakeholder

Someone with a significant stake in the outcome of an organization or project. These can be investors, distributors, recognizable name talent, or high-level crew.

Donor

Someone who has donated to your cause, project, or organization.

Patron

Similar to donors, and can refer to high-level donors or financial backers on the website Patreon. For examples of patrons, see below. you can be a patron for me and support the creation of content just like this by clicking below.

Non-Profit Organizations (NPO)

An organization dedicated to providing a good or service to a particular cause without the intent to profit from their actions, in the same way, a small business or corporation would. This designation often comes with significant tax benefits in the United States.

501c3

The most common type of non-profit entity file is to take advantage of non-profit tax exempt status in the US.

Non-Government Organization (NGO)

Similar to a non-profit, generally larger in scope. Also, something of an antiquated term.

Foundation

An organization providing funding to causes, organizations and projects without a promise of repayment or ownership. Generally, these organizations will only provide funding to non profit organizations. Exceptions exist.

Grantor

An organization that funds other organizations and projects in the form of grants. Generally, these organizations are also foundations, but not necessarily.

Fiscal Sponsorship

A process through which a for-profit organization can fundraise with the same tax-exempt status as a 501c3. In broad strokes, an accredited 501c3 takes in money on behalf of a for-profit company and then pays that money out less a fee. Not all 501c3 organizations can act as a fiscal sponsor.

Investment

Capital that has been or will be contributed to an organization in exchange for an equity stake, although it can also be structured as debt or promissory note.

Investment Deck (Often simply “Deck”)

A document providing a snapshot of the business of your project. I recommend a 12-slide version, which can be found outlined in this blog or made from a template in the resources section of my site, linked below.

Related: Free Film Business Resource Package

Look Book

A creative snapshot of your project with a bit of business in it as well. NOT THE SAME AS A DECK. There isn’t as much structure to this. Check out the blog on that one below.

Related: How to make a look book

Audience Analysis

One of 3 generally expected ways to project revenue for a film. This one is based around understanding the spending power of your audience and creating a market share analysis based on that. I don’t yet have a blog on this one, but I will be dropping two videos about it later this month on my youtube channel. Subscribe so you don’t miss them.

Competitive Analysis

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. This method involves taking 20 films of a similar genre, attachments, and Intellectual property status and doing a lot of math to get the estimates you need.

Sales Agency Estimates

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. These are high and low estimates given to you by a sales agent. They are often inflated.

Related: How to project Revenue for your Independent Film

Calendar Year

12 months beginning January 1 and ending December 31. What we generally think of as, you know, a year.

Fiscal year

The year observed by businesses. While each organization can specify its fiscal year, the term generally means October 1 to September 30 as that’s what many government organizations and large banks use. Many educational institutions tie their fiscal year to the school year, and most small businesses have their fiscal year match the calendar year as it’s easier to keep up with on limited staff.

Film Distribution

The act of making a film available to the end user in a given territory or platform.

International Sales

The act of selling a film to distributors around the world.

Related: What's the difference between a sales agent and distributor?

Bonus! Some common general use Acronyms

YOY

Year over Year. Commonly used in metrics for tracking marketing engagement or financial performance on a year-to-year basis.

YTD

Year to Date. Commonly used in conjunction with Year over year metrics or to measure other things like revenue or profit/loss metrics.

MTD

Month to Date. Commonly used when comparing monthly revenue to measure sales performance. Due to the standard reporting cycles for distributors, you probably won’t see this much unless you self-distribute.

OOO

Out of Office. It generally means the person can’t currently be reached.

EOD

End of Day. Refers to the close of business that day, and generally means 5 PM on that particular day for whatever the time zone of the person using the term is working in.

Thanks for reading this! Please share it with your friends. If you want more content on film financing, packaging, marketing, distribution, entrepreneurialism, and all facets of the film industry, sign up for my mailing list! Not only will you get monthly content digests segmented by topic, but you’ll get a package of other resources to take you film from script to screen. Those resources include a free ebook, whitepaper, investment deck template, and more!

Check the tags below for more related content!

IndieFilm Distribution Payment Waterfalls 101 (How Distributors Pay Filmmakers)

If you want to build a career as a filmmaker, you need to make money. If you want to make money, you need to understand how it works in your industry. Here’s a primer for that in indie film distribution.

I’ve been quoted as saying that investors get the short end of the stick in film investment. They end up putting up all or most of the money and then are often left with their hands out. They’re the last to get paid on the production, and the system is structured in such a way that it’s almost impossible to create a sustainable investor class.

I wrote an entire 7-part blog series on WHY film investment is in the tubes, so I don’t need to do that again. This blog will focus on exactly what I mean about investors being the last to be paid when filmmakers don’t get any profit share until after the investors have recouped. The answer to this question lies in the standard distribution waterfall

But before I list it out for you, I should make a point of saying that this is only true if you pay yourself either a stipend or a salary to produce the film. If anyone is working 100% deferred, then it’s relatively likely that they’ll get paid after the investor. However if you paid yourself to make the film in any way, then you have been paid before the investor, often using their money.

So what is a waterfall? A waterfall is how money from foreign sales and domestic distribution deals flows to the filmmaker. The top of the waterfall is the money source, and the bottom of the waterfall is the filmmaker. They normally look something like this, if the buyer is paying an MG or a License fee to the sales agent.

Buyer License fee/MG

Distributors fees/wire transfer fees.

Sales Agents Commission (20-35%)

Sales Agent’s Recoupable Expenses (up to cap)

Producer’s Representative Fees (If applicable, 5-15%)

Production Company fees

Debt

Equity Investor Investor (Until recoupment+10-20%, then 50% of future profits)

Crew Deferments

Producer share

If the buyer is offering a revenue share deal (Rev Share) then the waterfall will look more like this.

Individual Sales (Total)

Buyer’s Commission (20-30%)

Distributors fees/wire transfer fees.

Sales Agents Commission (20-35%)

Sales Agent’s Recoupable Expenses (up to cap)

Producer’s Representative Fees (If applicable, 5-15%)

Production Company fees

Debt

Investor (Until recoupment+10-20%, then 50% of future profits)

Crew Deferments

Producer share

Generally, a Production Company won’t see ANY money until the sales agent has recouped their expenses. Once they have, that item is essentially removed from the waterfall.

The four subcategories underneath the production company are generally what happens after the production company receives money from the sales agency. Admittedly, the investor is at the top of that waterfall (if we exclude the payments made in production) but they’re at the bottom of another.

Each piece of the Waterfall takes a slice of the film. For this example, we’ll assume the sales agent has already recouped their expenses. We’ll assume another 10,000 dollar sale has come in for easy math. So in the first waterfall, the sales agency takes 20% or 2,000 USD, then the remaining 80% (8000) goes down the line.

Then let’s say that your Producer’s rep has done their job and gotten a good deal for you. They charge the average price which is 10%. So the Producer’s Rep takes 10% of the 8,000 dollars, or 800, and passes the remaining 7,200 on to the filmmaker. The filmmaker then passes uses that money to back to their investor, settles up with crew deferments, and then pays themselves whatever is left.

If that same 10,000 USD was the result of a revenue share distribution agreement, it would look like this. First, the distributor takes 20%, then passes not he remaining 8,000 USD to the sales agent. Next the Sales agent takes 20% of the 8000 (1600) and passes the remaining 6,400 to the producer’s rep. The Producer’s rep takes 10% (640) and passes the remaining 5760 to the production company.

In both these examples I’ve ignored wire fees, but they can range from 1-3%.

One thing that you might notice is that the Sales Agency Commission is above their recoupable expenses. This does mean that they’re taking out their commission before they start to pay themselves back their recoupable marketing expenses. This is common, and while I don’t agree with it it’s a very difficult thing to negotiate. That being said, it doesn’t make as big of a difference to the bottom line as you might think. I’ve done the math, and it often amounts to around 4,000 to 5,000 extra for the sales agent. I know that’s far from nothing, but it’s the comparably small amount means there are better places to focus the negotiation.

There are a few tactics that you can use to get a better deal and change the waterfall around a bit, but those are tactics that I’m going to leave out of my blog, due to them requiring a deft hand to execute properly.

On that note, you might notice the extra line item for your producer’s rep, if you’re using one. You might also think why would you pay an extra 10% to a producer’s rep? The real answer is that a bad producer’s rep won’t really help you that much. But a good producer’s rep can not only ensure you get the best deal possible but also that it’s with the best company possible for your film.

A good producer’s rep will help streamline the sales agency selection process and occasionally handle domestic distribution themselves. They’ll also know exactly which parts of a distribution contract can be negotiated, and which ones can’t. They’ll generally have long-term relationships with many sales agencies, so the negotiations are likely to go smoothly. In short, a good Producer’s Rep might take a piece of the pie, but they’ll make the pie much bigger while they do. (See our services for more)

So there’s a primer, but there’s obviously a lot more to know. If you want to dive right in and find out what you need to know to grow your independent film company or career, a great place to start is my indiefilm business resource package. In addition to monthly mailings with the content you need to know to grow your career, It’s got an E-book, templates for decks, distributor content tracking, and exclusive updates on Guerrilla Rep Media Releases and content. It’s totally free, check it out below.

Use the tags below to find more related content

The 9 Ways to Finance an Indiependent Film

There’s more than one way to finance an independent film. It’s not all about finding investors. Here’s a breakdown of alternative indie film funding sources.

A lot of Filmmakers are only concerned with finding investors for their projects. While films require money to be made well, there’s are better ways to find that money than convincing a rich person to part with a few hundred thousand dollars. Even if you are able to get an angel investor (or a few ) on board, it’s often not in your best interest to raise your budget solely from private equity, as the more you raise the less likely it is you’ll ever see money from the back end of your project.

Would you Rather Watch or Listen than Read? I made a video on this topic for my YouTube Channel.

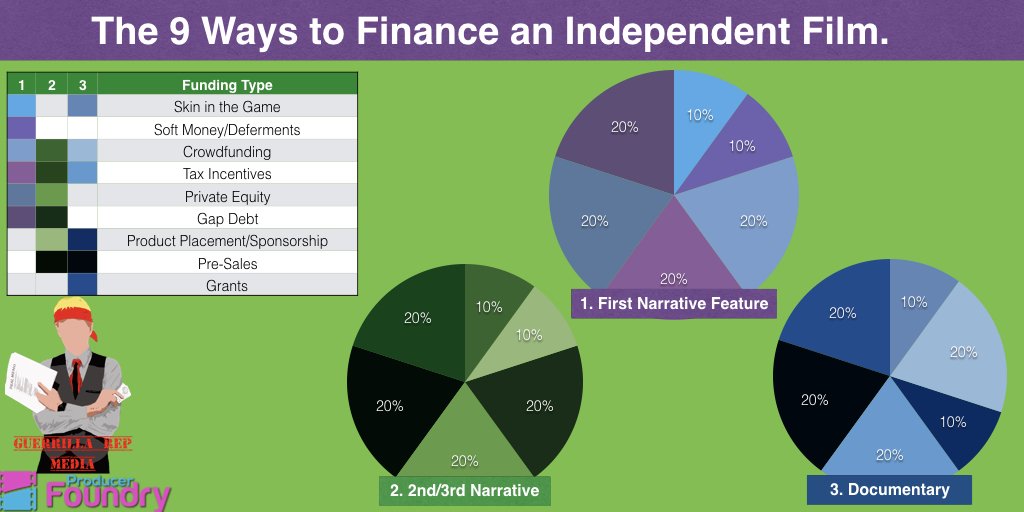

So here’s a very top-level guide to how you may want to structure your financial mix. The mixes in the image above loosely correspond to the financial mix of a first-time film, a tested filmmaker’s film, and a documentary. They’re also loose guidelines, and by no means apply to every situation, and should not be considered financial or legal advice under any circumstance. This is just the general experience of one Executive producer.

Piece 1 — Skin in the game. 10–20%

Investors want you to be risking something other than your time. The theory is that it makes you more likely to be responsible with their money if you put some of yours at risk. This can be from friends and family, but they prefer it come directly from your pocket.

I've gotten a lot of flack for this. However, the fact investors want skin in the game is true for any industry or any business. Tech companies normally have skin in the game from the founders as well, not just time, code, or intellectual property.

However, if you’ve got a mountain of student debt and no rich relatives, then there is another way…

Piece 2 — Crowdfunding 10–20%

I know filmmakers don’t like hearing that they’ll need to crowdfund. I understand it’s not an easy thing to do. I’ve raised some money on Kickstarter and can verify that It’s a full-time job during the campaign if you want to do it successfully. However, if you can hit your goal, not only will you be able to put some skin in the game, and retain more creative control and more of the back end but you’ll also provide verifiable proof that there’s a market for you and your work. Investors look very kindly on this.

That said, just as success provides strong market validation as a proof of concept, failing to raise your funding can also be seen as a failure of concept. and make it more difficult to raise than it would otherwise have been. Make sure you only bite off what you can chew.

Due to the difficulty in finding money for an independent film, the skin in the game or crowdfunding portion of the raise for a director’s first project is often a much higher percentage of the raise than it will be for their future projects.

Piece 3 — Equity 20–40%

Next up is equity. This is when an investor gives you money in return for an ownership stake in the company. From a filmmaker's perspective, it’s good in that if everything goes tits up, you don’t owe the investors their money back. Don't misunderstand what I mean by this. You ABSOLUTELY have a fiduciary responsibility to do your due diligence and act in the best interest of your investors to do absolutely everything in your power to make it so they recoup their investment. If you do that, or if you commit fraud, your investors can and likely will sue the pants off of you. You’ll have an uphill battle on that as well since they probably have more money for legal fees than you do.

Also, you will need a lawyer to help you draft a PPM. You shouldn't raise any kind of money on this list without a lawyer, with the possible exception of donation-based crowdfunding or grants. In general, just remember that I’m a dude who produced a bunch of movies who writes blogs and makes videos on the internet. Not a lawyer or financial advisor. #Notlegaladvice #Notfinancialdvice #mylawyermakesmewritethesesnippets.

It’s bad in that if everything goes extremely well, they get a huge percentage of your film. So it deserves a place in your financial mix, but ideally a small one.

For a longer list of my feelings on this topic, check out Why film needs Venture Capital, or One Simple Tool to Reopen Conversations with Investors

Piece 4 — Product Placement 10–20%

Product placement is when you get a brand to compensate you for including their product in your film. It’s more common in the form of donations or loans for use than hard money, but both can happen with talent and assured distribution. If you’re a first-timer, it’s difficult to get anything other than donated or loaned products.

Piece 5 — Presale Backed Debt 0–20%

Everything you read tells you the presale market has dried up. To a certain degree, that is true. However, it’s more convoluted than you may think. According to Jonathan Wolfe of the American Film Market, the presale market has a tendency to ebb and flow with the rise and fall of private equity in the filmmaking marketplace. There’s been a glut of equity for the past several years that’s quickly drying up.

That said, there are a lot of other factors that will determine where pre-sales end up in a few years. The form has shifted, in that it’s generally reputable sales agents that give the letters instead of buyers and territorial distributors. You then take that letter to a bank where you can borrow against it at a relatively low rate.

Piece 6 — Tax incentives 10%-20%

While many states have cut their filmmaking tax incentives, it’s still a very viable way to cover some of the costs of making your project. It is worth noting that the tax incentive money is generally given as a letter of credit, which you can then borrow against or sell to a brokerage agency. It’s not just a check from the state or country you’re shooting in. This system of finance is significantly more viable in Europe than it is in the US, but no matter where you plan on shooting it needs to be part of your financial mix.

Piece 7 — Grants 0–20%

There are still filmmaking grants that can help you to make your project. However, that’s not something that is available to all filmmakers, especially when they’re first making their projects. Don’t think grants don’t exist for you and your project, because they probably do, spend an afternoon googling it. My friend Joanne Butcher of www.FilmmakerSuccess.com suggests applying for one grand a month for the indefinite future, as when you do so you’ll develop relationships with the foundations you contact which can be invaluable for your career growth.

Grants are much easier to get as a completion fund once you’ve shot your film. Additionally, films made overseas are more likely to be funded by grants than those shot here in the US.

Piece 8 — Gap/Unsecured Debt 10–40%

Gap debt is an unsecured loan used to create a film or television series. This means that the loan has no collateral, be it product placement, Presale, or tax incentive. It used to be handled by entertainment banks for a very high interest rate, I can’t say who my source was on this, but I have heard of interest rates in excess of 50% APR. That market has been largely taken over by private investors loaning money through slated, which did bring interest rates down. Unsecured debt almost certainly requires a completion bond, which generally means that it’s only suitable for projects over 1mm USD in budget.

In general, you should use this form of financing as little as possible, and pay it back as quickly as possible. Again, Not legal or financial advice.

Piece 9 — Soft money and Deferments — whatever you can

Soft money is funding that isn’t given as cash. This can be your crew taking deferred payment for their services, or receiving donated or loaned products, locations, and anything else meant to get your film made. This isn’t so much funding as cost-cutting. It often includes donations or loans from product placement.

If you like this content and want to learn more about film financing, you should consider signing up for my mailing list. Not only will you a free e-book, but you’ll also get a free deck template, contract tracking templates, and form letters. Plus you’ll stay in the know about content, services, and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media.

Diversification and soft incentves in the film industry.

Film tends to not be an attractive investment, but it has some unique advantages that help it stand out and can make it worth your investors giving you the money you need to make your project. Here’s a few of them.

In this blog series, we’ve been talking a lot about why filmmakers would invest in an independent Film. Sadly, if you go by numbers alone the answer is that they shouldn’t. Film investment is an unpredictable, volotile, high risk endeavor. But, if you’re the type that isn’t scared by that, there are some reasons to considerer it. Sure, it will probably never make you as much money as tech, but it might has other benefits that aren’t offered by tech investment.

1. Smaller Potential Downside

If a Tech company fails to exit, generally you’re out everything you put in. Films exit once they’re completed, and investors begin recouping when they do. Further, a smart filmmaker won’t fund their project solely by equity, si the investor is more likely to get their money back. So, while you may not have be able to find a decacorn, the potential to lose everything you put in is somewhat less likely. It can be even less likely if you invest in finishing funds.

2. Tax Credits

Nobody likes to pay Uncle Sam, most people would rather see their name in lights than pay the government. Many states offer a tax incentive to get filmmakers to attract productions outside of territory. Often, those incentives are structures as tax credits an investor could buy at about 85-90 cents on the dollar. Other commissions offer it as a rebate that goes back to the filmmakers and subsequently back to the investors, if it’s not re-invested to finish the film.

3. Diversification

A strong investment portfolio is a diversified investment portfolio. Some industries do better than others when times are tough. Historically, Film is a sector that’s somewhat reversely dependent on the economy. That means when there’s a downturn, film investments sometimes do better. The period of greatest growth was in the great depression, and until recently it’s still been one of the least expensive ways to get out of the house.

But will that continue to be true? Perhaps not. Theater sales are continually declining, and DVD sales are in the toilet. However, in todays world, most independent films never get a theatrical release. if they can market themselves to the right audience, they can still make sales to people in their homes, for less than a cup of coffee. Admittedly that marketing job is no small feat.

Even if you don’t want to invest in social activism, you can enable an artist to create something that brings joy into the hearts of countless people. Sometimes by scaring the pants off of them. The arts are more than just storytelling, they help us communicate who we are as a people. In many ways I know more about Luke Skywalker than I do about my uncle, and more about Harry Potter than most of the people I went to my real high school with. These cultural touchstones have a huge impact on who we are as a society.

The US is terrible about helping to fund the arts and culture, so to some degree it comes down to society itself to perpetuate it’s own culture. If you can afford to help filmmakers make better movies, you should consider it

4. Supporting Arts and Culture

While every cultural or artistic entrepreneur should learn how to make their money back, it’s not the sole purpose of any cultural or artistic endeavor. It’s about communicating an idea, perhaps for entertainment or perhaps to spend a different level of consciousness.

If there’s a cause you care about, you should fund some filmmakers looking to do more to spread awareness of that cause. Then when you tell your friends to watch it to share your views, you also get the benefit of making a sale. Many ideas were only able to take root through the power of mass media.

5. Non-monetary incentives.

We all have hobbies, most of them cost us far more than they make us. If you’re the sort of person who can afford to lose 5 figures here or there, investing in films can be very interesting. if you can’t afford quite that much, you may want to look into different funds. I’m in the process of starting one, you can find out more here.

Some of my best friends became my friends because we talked about the money behind the film industry. These non-monetary incentives might even be useful sooner than you would think. If you start networking with filmmakers you may even get a deal when it comes time to make your next whiteboard video from the filmmakers you invested in.

6. Do something other people aren’t

I hear you. that Nerd you were shouting in #4 has been replaced by hipster. Don’t worry, you’re about to go back to nerd, since I’m going to lay some science on ya. If we look at the general attractiveness of beards, we learn that as they’re less common, they’re more attractive. Now, whether or not to invest in film is a multifaceted concept. I’m not saying ti will help you find a lady, (or gentleman,) but I am saying that it’s almost certain to start an interesting conversation.

If you’re at a Silicon Valley Networking event, it’s important to seem like a very interesting person. The same is true for any party. Attraction is somewhat based on scarcity, so you want to stand out from the pack. Investing in films is a good way to do that. You never know how it might help you stand out from the pack and talk to that person over by the bar with their eye on you, be it for your interesting investment or your beard.

7. Glitz and Glamour

If you’re a tech investor, you may have made a lot of investments that made you a very good return. Some of them may have been solely for the strong potential for ROI, or because the entrepreneurs could execute and build something that made a return. It could have changed the world of B2B Payroll invoicing. But while those make a difference in the lives of many myself included, it’s not really exciting.

Film is different. You get to meet interesting creative people. You get to talk about things other than how that API with that box shaped thing that processes your payments isn’t working as you planned, or the calendar integration isn’t as easy as it should be. You get to see what happens on set, or what it was like meeting that guy from that Quinten Tarantino movie for a day. And when you’re done, you can talk to the people at the tech event and share some awesome stories.

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back with more next week about why more people don’t invest in film. In the meantime, if you want to consider investing in film, try joining Slated. They’re a great resource to help you find projects that give you the best chance at a return. While all of the things above are great, they’re not worth losing every cent you put in. Slated helps you rate your projects, and find the ones with the best chance of success.

This entire 7-part series examines why film is an unsustainable investment. Part of the reason for the lack of sustainability is the fact that not enough producers understand the investment metrics of the film industry, and not enough filmmakers understand the business side of their craft. To help counter this, I offer all of these blogs plus a FREE film market resource pack on you can get by clicking below. If you want to take your career to the next level, the resources it has in it are a great place to start. Plus you’ll get monthly blog digests with recommended reading to help you parse through the 100+ blogs on my site and more easily reference them when you need them.